Words: Alix Sharkey; Portraits: Jens Stuart & Jamie Tanaka

![]() N OASIS IN A DESERT OF TOURIST CAFES,

Shakespeare and Company

has fed and watered the 20th century's greatest writers - among them Beckett and Burroughs.

Fifty years on, we meet the octogenarian beatniks behind a crumbling Parisian landmark and

its San Francisco 'sister', City Lights.

N OASIS IN A DESERT OF TOURIST CAFES,

Shakespeare and Company

has fed and watered the 20th century's greatest writers - among them Beckett and Burroughs.

Fifty years on, we meet the octogenarian beatniks behind a crumbling Parisian landmark and

its San Francisco 'sister', City Lights.

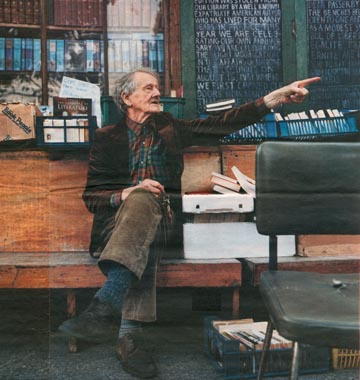

88 year-old Boston-born owner George Whitman, who arrived in Paris after the Second World War and never left |

Fifty years ago an American expatriate opened a bookstore on the left bank of the river Seine. Since then, some of the last century's greatest literary figures have passed through, to recite their work or consult the sprawling shelves of this curious 'rag-and-bone shop of the heart'.

Equal parts bookshop, library, hostel, museum and shrine, Shakespeare and Company is a place so otherworldly, so anachronistic, it seems to exist in a time warp. Even in Paris, a city noted for unexpected niches of quaint charm, it seems impossibly eccentric - a tiny enclave of radicalism, a place where strangers are invited to 'raid the icebox, kick off your shoes and lie in bed', an oasis of literary tranquillity in a desert of over-priced tourist cafés. On its walls are pictures of George the owner, together with his oldest friend, American poet and bookseller Lawrence Ferlinghetti, proprietor of another great literary institution, San Francisco's City Lights bookstore. The two men describe their businesses as 'sister bookshops', though there is little in the way of family resemblance - City Lights is a tight, professional ship. The family bond rests in their shared love of literature and poetry, their devotion and commitment to the power of words.

George (everybody calls him George) is now 88 years old, while Ferlinghetti (not even George calls him Lawrence) is the spring chicken, at 82. A combined century of bookmanship unites them; bibliophiles both, writers, promoters and publishers of literature and poetry, they have fed and sheltered, entertained, edited, published and paid some of the giants of 2oth-century letters, helping countless lesser names along the way.

And Shakespeare and Company is perhaps the last vestige of the way of life that spawned them, a minuscule island of poetic resistance where the bottom line is always a sentence, and never number. The city of Paris has officially recognised the store as part of its patrimoine, but under what category? As a monument to the bohemian spirit that came to be known as 'Beat'? As testament to the vision of those ex-servicemen - people like George and Ferlinghetti - who dared to conceive a peace more exciting than war? As a beacon, perhaps, for the countless writers who have made Paris their home before ' and since, and will do in future?

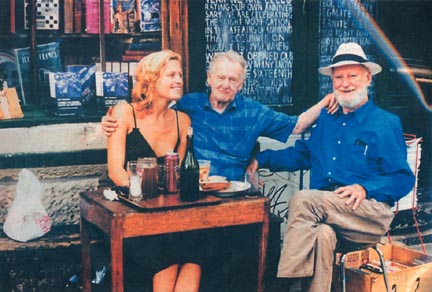

Bohemian rhapsody: Whitman and Ferlinghetti, survivors of the Beat generation, lunching with actress and former Shakespeare and Company employee Pia Copper. |

The shop itself is light on blockbusters, heavy on surrealism. In its centre stands a dry wishing-well, sprinkled with tourists, coins, the slogan 'live for Humanity' spelled out on its base. There are books, of course, but they are stacked haphazardly on sagging shelves and in musty corners, while power tools and extension leads are stuffed under tables creaking with dry tomes and piles of National Geographic. At the back of the shop, past a mirror covered in yellow cuttings and photos of George Soros (rumoured to be a benefactor), beyond cubbyholes, glass cabinets, dusty alcoves and another anthemic slogan, 'Be Not Inhospitable to Strangers Lest They Be Angels in Disguise', a wooden staircase leads up to the childrens section and more rooms, their ceilings cracked and blackened from the fire that almost razed the store in 1991

THE FOUNDATIONS WERE LAID A THOUSAND YEARS ago; in the 16th century the place was a monastery, and it reeks of age: twisted oak beams and crumbling plaster overhead, cracked and rusty tiles underfoot. The only nod to modernity is the exposed electrical wiring and a beige enamel paraffin heater in the corner, braced for another hard winter. Although George has steadily acquired more of the building, adding rooms one by one to his original ground-floor premises, little has changed since Anais Nin wrote in her Paris diaries of the 50s: "And there by the Seine was the bookshop... an Utrillo house, not too steady on its foundations, small windows, wrinkled shutters. And there was George Whitman, undernourished, bearded, a saint among his books, lending them, housing penniless friends upstairs, not eager to sell, in the back of the store, in a small overcrowded room, with a desk, a small stove. All those who come for books remain to talk, while George tries to write letters, to open his mail, order books. A tiny, unbelievable staircase, circular, leads to his bedroom, or the communal bedroom, where he expected Henry Miller and other visitors to stay."

Today, these rooms are filled with the hush of time. Even at midday, as traffic roars along the Quai de Montebello, this is a sanctuary for thought and reflection, simultaneously shabby and luxurious. Occasionally a newcomer wanders in and stops mid step, unsure if some invisible boundary between public and private has been breached, unaware that, for George, such boundaries barely exist.

And, everywhere, the books, stacked every which way, books and more books, lining walls from floor to ceiling, piled on shelves and chairs and tables. Books of all sizes, mostly hardback, mostly English , from Cicero via Chaucer to Chomsky. In the American political section, a first edition of At Ease: Stories I Tell To Friends by Dwight D. Eisenhower (1954) nestles alongside The Bush Dyslexicon by Mark Crispin Miller, published this year.

Once the eye adjusts to the spines, you notice the suitcases, backpacks, T-shirts and towels peeking from behind bookcases, the sleeping bags propped in comers, threadbare carpets on makeshift benches that double as beds when the store closes at midnight.

George welcomes them all, feeds them all, lets them stay as long as they want. "I've been a communist all my life!" he barks when asked why, before explaining that he is simply repaying the kindness shown to him over 6o years ago when he set out to walk around the world. He never got further than central America, but that journey shaped his life; his house will always be open to writers and poets, to drifters, dreamers, students, teachers and romantic but penniless couples.

Guests can dean, cook or work in the shop. Or not. There are few rules, other than respect for fellow guests. Since there is no fire escape, the city authorities have told George to restrict customers to 15 at any one time. But twice that number often roam the store, and there are rarely fewer than a dozen sleeping there. Last summer, there were around 18 though nobody knows for sure.

The current 'house mother' is Julia, a 23 year-old German dancer, studying in Paris. She came for a week and, six months later, she's still sleeping in the children's section over the stairs. "It's fantastic," she beams, "you get to meet so many wonderful people from all over the world." Later, she helps George prepare soup for her fellow guests: Andreas from Sweden, Stephen from London, Julia and Stefano from Italy, Thirza, an 'AngloFrench Israeli', Ludmila and Victoria from Buenos Aires, and Francisco, a teenage Spaniard from Berlin. George loses track sometimes, and is often seen peering at customers, wondering if they live on his premises.

"One man has been living here for five years," he says proudly, "an English guy. Started out he was a drunken bum, working in advertising, very well paid job, but he hated it, became an alcoholic. Anyway, he came over here, stopped drinking, got some of his poetry published, now he's doing translations, he's changed his whole life."

These life-enhancing qualities are echoed on the shop's website, where middle-aged Americans post testimonials about Paris in the 60s, and how George introduced them to poetry, friendship and sharing, to life itself

GEORGE WANDERS UPSTAIRS ABOUT 5.30 PM. A SMALL, WITHERED MAN WITH TINY, BIRD-LIKE EYES, his brown cords are shiny with grime, his white shirt crumpled and wine-stained, his shoes scuffed. His bedroom doubles as his office, and his bed is buried under piles of books, magazines and manuscripts.

Here, he sits at his battered desk, writing, reading, ordering books, as he has for decades, while curious shoppers poke their noses around the door, intrigued by this grizzled, white-haired little man in his tatty clothes, surrounded by papers and books and newspaper clippings, growling about propaganda and culture and democracy and communism while water drips from the door frame behind him into a red plastic bucket.

There's a leak upstairs, and he was going to call the plumber, and anyway, he got some cash out and ... he looks flustered, embarrassed.

"Well, I must have put it down somewhere and it just disappeared. I guess someone came in and took it. It was a lot of money, too." Really, how much? "Oh, I don't know, I didn't count it, but it was a big handful of cash. Several thousand francs."

There are tales of customers pulling books from the shelves and finding thousands of francs inside, money that George had forgotten even existed.

George is notoriously bad at holding on to money, famously indifferent to making it. There are tales of customers pulling books from the shelves and finding thousands of francs tucked inside, money that George had forgotten even existed. "Every time I hear about a man being arrested in Times Square for handing out dollar bills," he freely admits, "I think there but for the grace of God go I." The view from his desk could make him rich overnight, should he sell his labyrinthine property to the highest bidder. directly across the river stands the brooding Gothic mass of Notre Dame. But George hates property speculation, complaining bitterly about the guy who's turning the building next door into a four-star hotel, as if there aren't enough expensive hotels and cafes in the area.

"It's a corporate world," he sighs. It's been a struggle, and he's getting tired now, but he still battles to keep that world from his doorstep, where a completely different one begins.

THE SHAKESPEARE AND COMPANY STORY BEGAN EARLY LAST CENTURY, when Paris became the spiritual home of a loose group of writers known as the Lost Generation, including Hemingway, Joyce, Pound, Wolfe, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos and Stein. Attracted by the city's beauty, culture and permissive attitudes, they also found it exceptionally cheap. In particular, the Sorbonne area was fill of cheap hotels, restaurants and bars. Even the grander Belle Epoque establishments were affordable, and a new, avant-garde literary tradition flourished in Left Bank cafes such as the Flore, Lipp, Deux Magots and Tournon. This was the Parisian milieu Hemingway famously described as a 'movable feast'.

American expatriate Sylvia Beach's English-language bookshop on rue de l'Odéon, called Shakespeare and Company, soon became the place for this expat literati to meet French counterparts including Man Ray, Jean Cocteau and André Gide. Its place in history was assured when Beach published a controversial work by an unknown writer, already rejected by several other publishers: Ulysses, by James Joyce. But, following the Nazi occupation, Beach closed the store and put her most valuable books into storage, before being sent to an internment camp. A contact in the Vichy government obtained her release, and, by 1944, she was back in Paris as Allied troops arrived to liberate the city, climaxing in a reunion that could have been scripted in Hollywood. Amid the sound of exploding shells and sniper fire, she heard someone calling her name: it was Hemingway,

"I flew downstairs," she later recalled, "We met with a crash; he picked me up and swung me around and kissed me while people on the street and in the windows cheered." But while Beach survived, her bookstore never reopened.

After the Second World War, a new wave of expat writers, many of them American veterans studying on the GI Bill, came in search of the same magic that had attracted the novelists, poets and artists of the 20s and 30s. Like their predecessors, they subscribed to Gertrude Stein's dictum: "It's not so much what Paris gives you, as what it doesn't take away."

Black American writers such as Chester Himes, James Baldwin and Richard Wright found a city where their art was taken more seriously than their colour. "There is such an absence of race hate that it seems a little unreal," observed Wright. Another American expat novelist, William Styron, noted that, in Paris, "A writer is esteemed, respected... necessary to the intellectual life of his country." Attitudes were also more liberal regarding sexual preferences, since the Napoleonic code had effectively decriminalised homosexuality in the 19th century. Consequently, gay artists and writers felt more at ease here than in London or New York. And on the Left Bank they found an affordable central district where writers and artists met to talk and drink, where accommodation was cheap and the working-class locals tolerant of the bohemians and students in their midst.

By 1951, George Whitman had already spent five years in the area, and fallen in love with 'the cultural capital of the world'. A Boston native, his childhood had been spent globetrotting with his father, a travelling physics professor, through China, Greece,

Turkey and Western Europe. After studying for a degree in journalism at Boston University, he set off on a seven-year, proto-hippie trek through North and Central America, hitch-hiking and begging, working where he could. More than 6o years later, he can still remember meals he ate and people who fed him. It was this journey, he says, that shaped his politics and social conscience, opening his eyes to stark differences between his homeland and its poorer neighbours.

After Latin American studies at Harvard and two years with the Merchant Marines during the Second World War, he had sailed for Paris in 1946 to work in a camp for war orphans. When it disbanded, George, now in his mid-30s, enrolled to study French Civilisation at the Sorbonne. US war veterans could claim a handsome book allowance by submitting receipts to the Veteran's Association. He made good use of this perk, and his tiny room in the Hotel de Suez, on the boulevard St Michel, was soon lined with books on literature, philosophy, politics and history. "In those days," he recalls, "there was a shortage of everything, so books were precious, valuable, highly sought-after things."

His 'library' soon became a meeting point for like-minded expatriates, and since it had no lock- he often returned to find strangers reading in his room. Glad of the company, he would invite them to stay for dinner. Another ex-serviceman, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, arrived in Paris in 1948 to study for his doctorate in poetry at the Sorbonne, with a letter of introduction from George's sister, whom he had met at Columbia University.

"He was living in this little 8ft by 8ft room," remembers Ferlinghetti, "no windows, and books stacked up to the ceiling on three sides And there was George in the middle, reading in this broken-down armchair."

Though they became friends, Ferlinghetti says they were never particularly close - perhaps due to their very different attitudes to their host country. While George has always retained a certain distance from French culture, Ferlinghetti had roots in France - shortly after his birth, his mother was committed to a mental asylum and he was sent to France to be raised by a female relative. It wasn't until his return to America, at the age of five, that the future poet learned to speak English.

"I don't think George gets too close to anyone,' says Ferlinghetti. "He's very formal in a way. Like he still writes to me and signs his letters, 'Amitie sincere.' Sincere friendship. Very formal."

Inevitably, the tiny hotel room expanded into a tiny bookstore when, having come into a small inheritance, George bought an Arab grocery overlooking the Seine and trans formed it, according to author Barry Miles in his book The Beat Hotel, "into a combination bookshop, youth hostel, and social club. Upstairs, he had a reading room with beds where visiting writers and poets were welcome to stay, free of charge, for up to a week and... the shop was used as a meeting place and mail drop by many expatriate Americans."

Originally called The Mistral, George would rename it in 1964 in honour of the late Sylvia Beach and the literary tradition she had done so much to establish. "All the stories that come out fail to note that he's not the original Shakespeare and Company," notes Ferlinghetti, "nor is he even in the same location." Did he think that was a problem? "He's certainly carried forth the glorious tradition, because he's a real bibliophile - and that's a dying breed these days."

The Mistral became a focus for Left Bank literary activity, with readings and gatherings taking place in the back room. Within a few months it gave birth to a small but influential literary magazine called Merlin, which included works by Jean Genet, Eugene Ionesco, Jean-Paul Sartre and an unknown Samuel Beckett. Merlin was followed by other local publications such as Paris Review and New Story, which featured young writers including Alison Lurie, James Baldwin, Terry Southern and Ray Bradbury. Meanwhile, entrepreneurial publisher Maurice Girodias engaged young writers and poets involved with Merlin to churn out pornographic potboilers with names like White Thighs and Roman Orgy for his Olympia Press, and used the profits to publish works by Beckett, Southern, Vladimir Nabokov, JP Donleavy; and others.

THE BEAT GENERATION, IN THE FORM OF ALLEN GINSBERG, WILLIAM BURROUGHS AND GREGORY CORSO, arrived in Paris in autumn 1957, settling into the so-called 'Beat Hotel' on rue Git-le-Coeur: 42 rooms, no carpets or telephone, it was filthy, squalid and cheap. And liberal. The concierge allowed tenants to cook and to take drugs in their rooms, and guests could stay at no extra charge. Burroughs, a self-professed connoisseur of sleaze, wrote to Jack Kerouac complaining that "...the WC [is] in an unspeakable condition, that fucking South American borracho pukes and shits all over the floor and the cats are also broked [trained] to shit there..."

While working on Naked Lunch, Burroughs would consult the medical books in George's library. He also attended the Sunday afternoon tea-parties.

Of course they soon found The Mistral, just a few minutes away, across the PIace St. Michel. "They were in and out of here nearly every day," recalls George, "and they were some of the first to come to my poetry readings, but they were very shy about it. They had to get drunk or take their clothes off, do foolish things like that, in order to feel part of the whole thing. I thought they were rather exciting," he adds, "but I don't think I realised how much influence their work would eventually have." While working on Naked Lunch, Burroughs would consult the medical books in George's library. He also attended the regular Sunday afternoon tea-parties. "This was before he got involved in all that cut-up business," growls George. "A lot of nonsense in my opinion. John dos Passos was doing the same thing years earlier, but much better, there was a method to it. It was rational." Ginsberg attended poetry readings and stayed for the communal meal that followed. "A couple of times he cooked for me over at his place," says George, "but his facilities weren't great, and generally I'd cook a lot so we used to eat upstairs here."

As well as borrowing money which he never repaid, Gregory Corso stole manuscripts, first editions and other valuable items from George, in order to sell them elsewhere. "He started out as a petty thief and pretty much kept it up all his life. He would steal from anybody, even friends, and he stole from me many times." At one point, the desperate poet offered George the handwritten manuscript of his new book in return for a loan. "So I loaned him some money against the manuscript and his notebooks, and of course he came back shortly afterwards and stole them back from me. He used to tell me that he made more money from selling his manuscripts and notebooks than from actual book sales. Eventually I realised why."

At one point, Gregory Corso was banned from both the bookstores. When I mention how he sold and stole back his own manuscripts, Lawrence Ferlinghetti is not surprised. The last time Como was in San Francisco, he recalls, he ran out of money while drinking in Vesuvio's [bar] next door. "The bookstore was closed. So he broke the window and robbed the cash register, I guess it must have been about $100. Anyway, the bar staff saw him and called the police, who dusted the register and got his fingerprints. My manager and myself went around to Gregory's house at six the next morning and said, 'You better get out of town, the police have got your number.' And he split and went to Italy, never came back to San Francisco at all." In fact, Corso died in Italy, and is buried in the Protestant cemetery in Rome. "Got himself buried right alongside Byron, his great hero. You know, you can't be buried there if you're Catholic. Of course, he was Catholic, his family came from Calabria. He told them he was Jewish. He pulled a fast one even in death."

EVEN AT 82, LAWRENCE FARLINGHETTI IS A TALL, WELLBUILT MAN, his pale colouring accentuated by a white button-down shirt over white T shirt, with khaki chinos and tan sneakers. His white eyebrows creep over large, pale-blue eyes; he is almost bald now, but still has a stubbly white beard and a tiny gold sleeper in his right earlobe. He sits with large hands folded in his lap, rocking in his reclining wooden chair, at an old wooden writing bureau. His triangular office looks out over the busy crossroads where Columbus Avenue meets Broadway in San Francisco's North Beach. His desk is every bit as neat and orderly as Whitman's is chaotic and sprawling, and where Shakespeare and Company has intense young people with piercings: and baggy jeans, his offices are staffed by serious thirtysomethings who look like they've just completed their second doctorate.

There still seems to be something of the naval officer about him. Ferlinghetti served in the U S Navy during the war, taking part in the Normandy landings. Later, he served on a troop transporter which docked in Japan. He and a friend took a train to Hiroshima, to see the damage from the bomb that had been dropped a week earlier. "Nobody knew anything about radiation," he recalls, "we just walked around. It was total mulch. Seemed to me the city was a couple of miles square, it was totally flat, with just a couple of walls still standing. It was just this mud with things sticking out ofit; people, parts of people, broken teacups, stuff. It was like a big soup."

Armed with his Sorborme doctorate and a feeling that culture's centre of gravity was heading westwards, Ferlinghetti left Paris for San Francisco in January 1951, where he found a buzzing art scene in the city's North Beach, stimulated by a heady mix of poetry, jazz, Zen philosophy and the city's liberal politics. "The returning GIs were a big factor in that - they were all alkies, they played jazz, they had these great drinking parties. Down here on Columbus, the Beats were all into pot - they werent really drinkers." He got himself a studio and started painting, but eventually returned to poetry and books, opened his City Lights bookstore, which published his own Beat poems in the classic collections Pictures of the Gone World and A Coney Island of the Mind and his definitive translation of Jacques Prévert's Paroles. He also edited and published other poetry, including Corso's Gasoline and Ginsberg's seminal Howl, for which he was tried and acquitted for obscenity in a landmark case for free speech.

Like its Parisian 'sister' store, the City Lights building has been acquired over decades, in piecemeal fashion. And while they are both, in their very different ways, great bookstores, the similarities end there. Ferhnghetti now owns the entire building on Columbus Avenue, the bookstore is selling more poetry than ever and he has long since established the City Lights Foundation, a non-profit organisation to ensure the continuity the store and its publishing ventures after his passing.

The future of Shakespeare and Company, however, remains one of unrealised dreams and looming deadlines. This year, in accordance with French law, the facade of the building must be scaffolded, repaired, Cleaned and repainted, the costs split between the three co-owners of the building. George's share will be something in the region of £18,000.

If he dies and doesn't make any provision, the store is full of signed books and letters from Anais Nin, Henry Miller... And it will all disappear.

Of course, he would like to create a foundation that would manage funds and oversee the development of his original ideal. He wants to buy more of the building, expand the store and create a real lending library on the third floor, with its own full-time librarian, and extensive digital resources. He'd like to open a 'Shakespeare Tea Garden' on the corner site, where he could open up his regular readings to a much larger audience, in more salubrious and comfortable conditions. "I'm not a good enough businessman to realise all my dreams," he sighs. His hope is that he can hand the business over to his 21-year-old daughter, Sylvia Beach Whitman, so that she can carry on the good work. Ferlinghetti has been in contact with George's brother, in an attempt to find a way to keep Shakespeare and Company going after his death. "He had a single-minded vision to have a great bookstore in Paris, and he's succeeded. At enormous personal cost, you might say. I'd have to leave that unexplained. He sacrificed everything for the bookstore, and it's a great bookstore." But the problem, says Ferlinghetti, is that George has never found someone dependable to run the place efficiently - or been able to keep them. "At present, he doesn't have anyone to take over the store when he dies, so we've got to figure out his foundation. The trouble is, if he dies and doesn't make any provision, the store is jammed full of signed books, letters and photographs from Anais Nin, Henry Miller, Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Durrell and plenty of others. And all that ephemera will disappear."

George, of course, refuses to get flustered. Asked about his legacy, he cracks a gap-toothed grin and waves my concern away. "A lot of people say a lot of stuff about how wonderful we are," he says. "So I'd like to apologise in advance for the general shabbiness." The sister bookshops are celebrating their centenary in business. Shakespeare and Company opened in 1951, City Lights in 1953, so they're going to split the difference and have a party in Paris on 15 August 2002. And George would like you to know that you're all invited.