Learn about the North Yukon study area and the grizzlies that inhabit it!

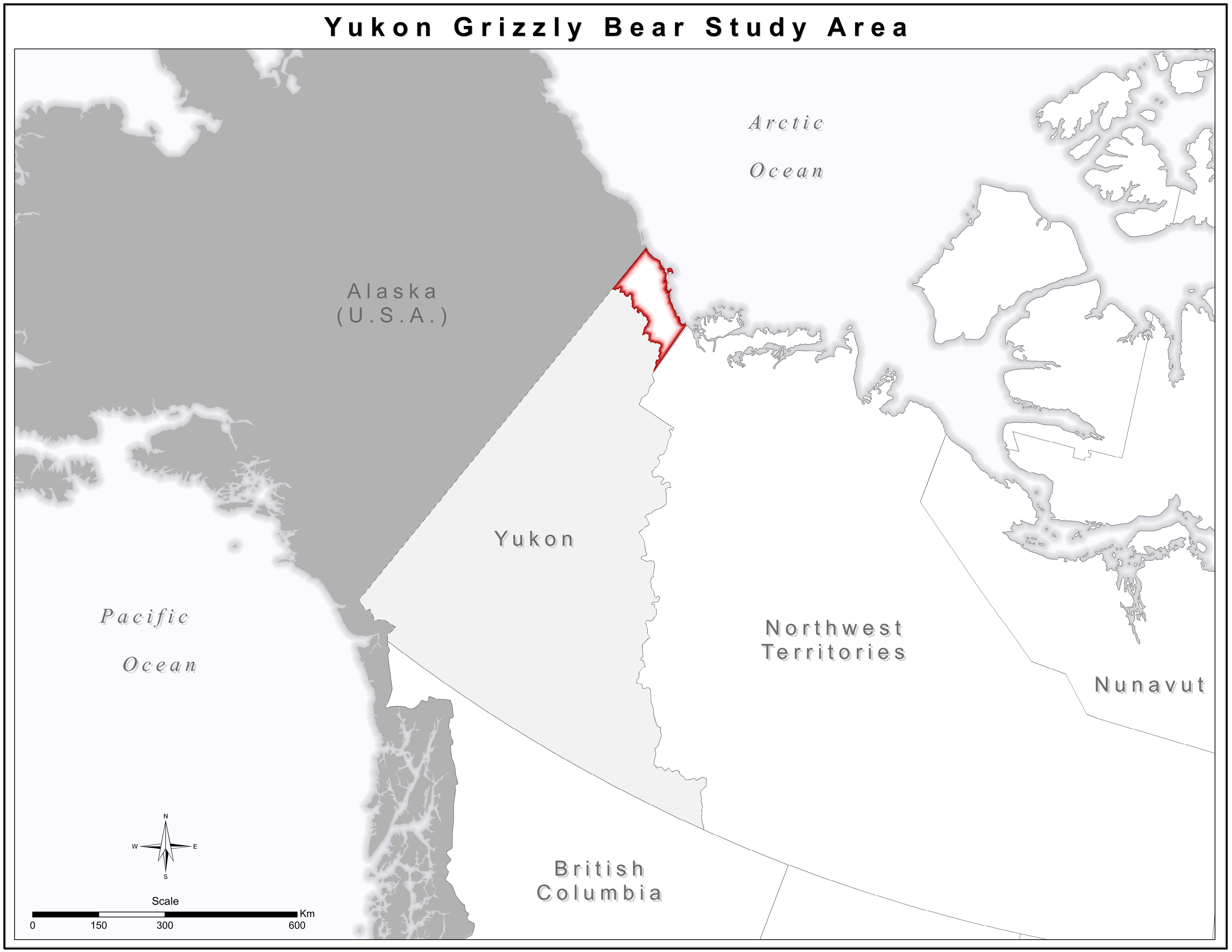

The study area is in the northern edge of the Yukon Territory known as the Yukon North Slope. The Yukon North Slope has no permanent settlements or roads, only the remains of historic whaling and military sites. The Inuvialuit move in and set up seasonal camps during the summer to hunt and gather to prepare for the winter. The low human impact makes this an ideal place to study grizzly bear movement without human influence.

The area has 24 hours of sunlight for a few weeks in summer and 24 hours of darkness for a few weeks in winter. This causes a climate with long winters and short growing seasons. The western portion of the study area is made of steep mountainous terrain which creates a very complex landscape. It contains narrow v-shaped valleys and tall mountain ridges which creates local differences in climate which creates local differences in vegetation. The vegetation in this area varies from bare rock to sedges and shrubs with occasional trees. The eastern portion is much less varied; it is a gentle northerly slope towards the Beauford Sea. The consistent topography creates consistent fields of sedges and shrubs.

Grizzly bears are omnivorous animals, and their diets mainly contain meats and plants. The main carnivorous foods of grizzly bears are including broad whitefish, snow goose eggs, muskrat, small mammals, terrestrial mammals and aquatic browsers (Edward et al., 2009). The main herbaceous foods are including horsetail, roots, and all berry species (Edward et al., 2009). Grizzly bears living in Yukon have different dietary habits between genders and seasons in order to contend with limited food availability. According to a stable isotope analysis on 51 grizzly bears’ hair and claw in the Mackenzie Delta region, grizzly bear diet is considered as sexually independent (Edward et al., 2009). Male grizzly bears generally have higher use of animal protein since they have larger body size and need high protein sources to restore their muscle mass. The result of the analysis shows that the carnivorous foods were contributed as an important secondary food source in male grizzly bear diets (Edward et al., 2009). Grizzly bear dietary habits also vary in different seasons. During spring and summer, the diet change from roots to horsetail and forbs since the growing of common horsetail shoots. But during fall, the diet of grizzly bear generally shifts to berries since the growing availability of bog blueberries. According to a research on Northern Yukon grizzly food habits, alpine hedysarum roots, over-wintered crowberries and common horsetail are the dominant plants food between May and June (Machutchon & Wellwood, 2003), while horsetail shoot and bearflower leaves are major food in June and July (Machutchon & Wellwood, 2003). Bog blueberries and alpine hedysarum roots are the most common food from August to September (Machutchon & Wellwood, 2003).

Wildlife managers have a need for a reliable, safe, and efficient way to collect information about animal populations. In our study of Grizzly bears (ursus arctos), Global positioning systems (GPS) collars are an integral tool for the collection and monitoring of spatio-temporal movement. (Heard, Ciarniello, & Seip, 2008.) The Bears are first located by helicopter, tranquilized and vital statistics are recorded. (Environment Yukon, 2013 Retrieved February 7, 2017) The GPS collar is then attached around the bear’s neck. Following this step the bear being woken up. These collars coupled with other sensors to collect additional data such as ambient temperature, and daily activity. (Telonics Inc, 2015, Retrieved February 2, 2017) By further analyzing the data collected from GPS Collars, patterns about the Bears can be identified and understanding clarified. The GPS collars gain locations data by trilateration of satellite signals. A minimum of three satellites must be in view in order to gain latitude and longitude coordinates, and an additional fourth satellite signal must be acquire to obtain elevation data. (Bajaj, Ranaweera, & Agrawal, 2002; Swanlund et al., 2016.) There are some challenges GPS collars face when trying to acquire satellite signal: topography, overhanging vegetation, and battery life. (Swanlund et al. 2016.) The collar in question is the Telonics Generation 3 collar. Swanlund et al. (2016) have tested Telonics Generation 3 model GPS Collars for fix rate accuracy and positional dilution of precision (PDOP). This study concludes with the result that the Telonics Generation 3 GPS collars perform exceptionally well in our Yukon study area. (Swanlund et al., 2016.)

Studies focused on the movement patterns of grizzly bears have found three

main influencing drivers: food availability, sex, body condition, and reproductive status,

and climate (Pigeon et al. 2016; Edwards et al. 2011; Mowat and Heard, 2006). The

primary factor influencing grizzly bear movement is food variety and availability,

especially during periods of den entry and exit (Pigeon et al. 2016; Edwards et al. 2011;

Mowat and Heard 2006). On a macro scale, grizzly bear populations found in coastal environments in British Columbia and the Northern United States rely more heavily on meat based foods than interior populations that derive much of their nutrients from plant foods (Mowat and Heard 2006).

Diet specialization not only differs between distinct populations inhabiting different environments, but within populations themselves. A single population study consisting of 51 grizzly bears within the Mackenzie Delta region of the Canadian Arctic highlights micro level diet specialization (Edwards et al. 2011). Three distinct foraging groups were identified within a single population ranging from near-complete herbivory to near-complete carnivory (Edwards et al. 2011). Grizzly bears relying more heavily on plant-based diet exhibit reduced movement rates as plant based foods are more abundant and require less foraging effort (Edwards et al. 2011).The opposite is found in bears consuming a diet predominantly based on animal foods. Although animal food sources are higher in nutritional content, these food sources are sparser and require higher foraging efforts resulting in increased rates of movement (Edwards et al. 2011).

Movement rates have also been linked to grizzly bear sex and body condition

(Edwards et al. 2011; Pigeon et al. 2016). Nutritional requirements of individuals vary

based on size and sex (Edwards et al. 2011). Larger body sizes of males require

greater amounts of protein, resulting in higher movement rates as foraging animal foods

involves increased effort (Edwards et al. 2011; Mowat and Heard 2006; Pigeon et al.

2016). In contrast, smaller body sizes of females and sub-adults allow for grizzly bears

to satisfy their nutritional needs with less nutrient rich but more abundant food sources,

reducing foraging efforts and movement rates (Edwards et al. 2011).During den entry and exit periods, sex and reproductive status have significant implications on movement behavior (Pigeon et al. 2016). Gestating females enter dens approximately 2 weeks earlier than males, while females lactating during hibernation periods remain in dens longer into the spring (Pigeon et al. 2016). Females accompanied by cubs alter den entry and exit date based on cub age, where younger

cubs result in earlier den entry and later emergence (Pigeon et al. 2016). Movement

decisions based on minimizing risks of predation, especially during den entry and exit

periods, more strongly influence females with cubs (Gardner et al. 2014).

Movement rates of grizzly bears are also affected by environmental factors in the

inhabited region (MacHutchon et al. 2003). Pigeon et al. (2016) suggested that climatic

influences are the strongest drivers of den entry and exit. Reduced precipitation rates

and higher spring temperature associated with southern populations result in earlier den

exits, while increases in snowfall seen in northern latitudes delay den exit (Pigeon et al.

2016). Grizzly bears in dryer areas with minimal snowfall have been

observed to consume more animal foods (Mowat and Heard 2006). This is largely due

to the high abundance and variety of ungulates in such climates, resulting in higher

rates of movement among grizzly bears as their trophic complexity increases (Mowat

and Heard 2006; Edwards et al. 2011).