Sustainability, Urban Density, and Land-use Diversity.

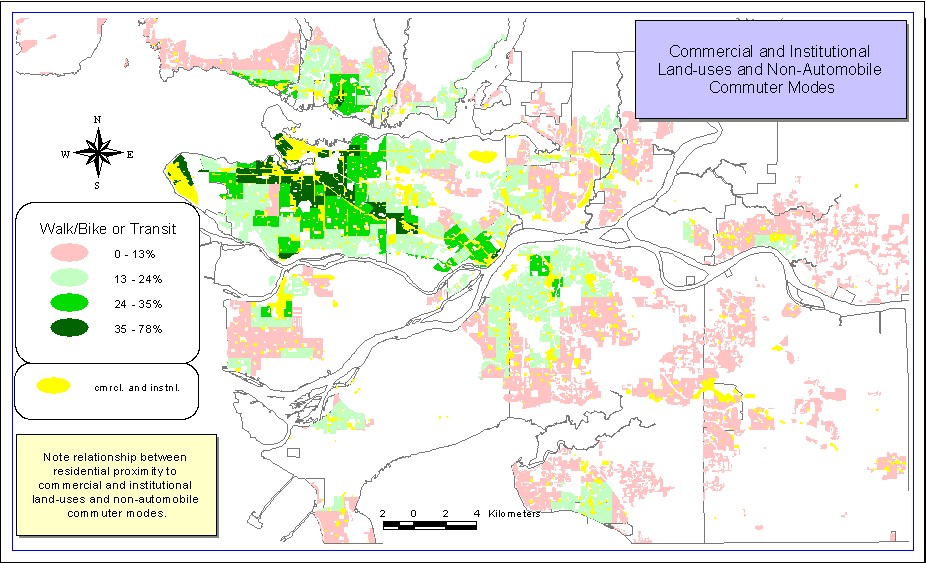

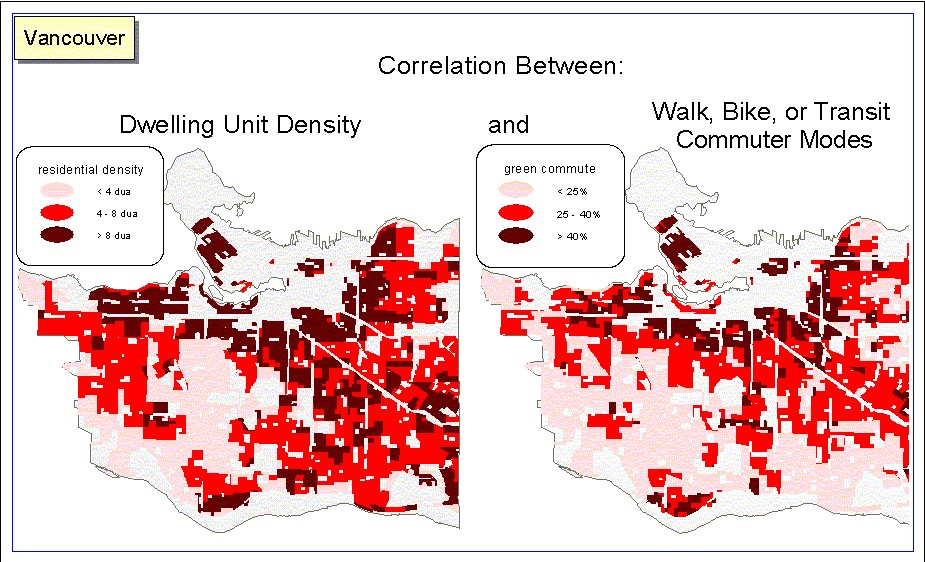

Guidelines for sustainable urban design are based on a preponderance of evidence showing that higher densities and compact patterns of development lead to higher rates of transit use (Bernick and Cervero, 1997; Brambilla, 1976;Ramsay, 1990). The smaller amount of research on the transportation implications of mixed-use environments show that transit, walk, and bike trips increase with proximity to retail shops and other non-residential uses Bernick and Cervero, 1997). Bernick and Cervero’s study of work trips across 11 large U.S. metropolitan areas showed non-residential uses within 300 ft. of ones residence lowered the probability of auto-commuting (88). A look at some GVRD statistics supports this research: approximately 18 per cent of the regions population lives within walking distance of the downtown or one of the regions regional town centres and account for 40 per cent of all work trips made by transit (GVRD 2001). The map below displaying 1996 census data shows the relationship between proximity to commercial and institutional uses and non-automobile commuter modes in GVRD municipalities. The map that follows shows a positive spatial correlation between high dwelling unit density (dua) and non-automobile commuter modes. Regression analysis comparing these same attributes also illustrates these correlations (Please see methodology ).

Bernick and Cervero’s ‘Transit-Village’ and Peter Calthorpe’s ‘Transit Oriented Development’ (TOD) are based on established comfortable walking distances that people will generally be willing to go to the store, a transit stop, and other every day destinations. These two design concepts are also based on established minimum dwelling unit and population densities above which transit service becomes financially feasible and service levels become frequent enough to make transit attractive. The minimum dwelling unit density required to support transit services varies somewhat between experts. Based on a variety of different research on densities, land-use, and transit use, including the seminal 1977 study by Pushkarev and Zupan, Cervero and Bernick set a minimum of 12 dwelling units per acre (dua) necessary to support moderate levels of rail transit service. The Sierra Club’s Dr. John Holtzclaw did research showing a bus every 30 minutes becomes feasible above 7dua, and every 10 minutes at 15dua. He claims that light rail service is feasible above 9dua, rapid transit above 12 dua, and that public transit use increases fourfold as density increases from 7to 30dua (Sierra Club Web-Site). Peter Calthorpe calls for an average of 15 dua in urban TOD’s. Smart Growth B.C. puts the minimum density necessary to support transit use at 8 dua, and is the figure I use in the analysis (Curran and Leung, 2000). ‘Human scale’ and more vibrant communities that foster high levels social interaction require densities of between 50 to 150 dua, says Jane Jacobs, and fellow Urbanologist Hans Blumenfield between 12 and 60 dua (Bernick and Cervero, 1997).

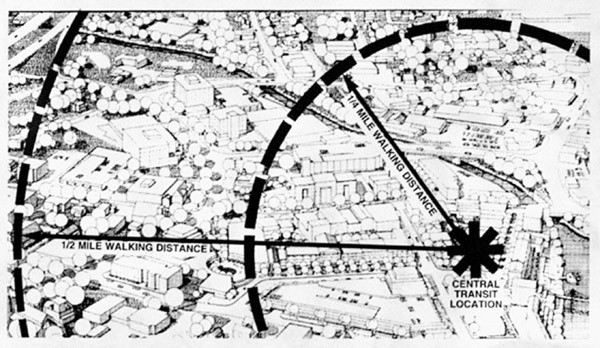

The structure, scale, and spatial organization of neighbourhoods is important in regards to urban sustainability. Amongst others, Jane Jacobs calls for neighbourhoods that are interconnected and organized into a non-hierarchical grid with short blocks and narrow streets, with attention to human scale and height-width proportionality (1961). Street grid patterns with short blocks such as those found in older, inner city locations increase horizontal connectivity between the various local land-uses. At the block level, lot sizes are no bigger than 33/100 ft., which allows for a dwelling unit density of 11 dua for single detached dwellings (Calthorpe, 1993). Provisions are made for high pedestrian levels such as wide sidewalks and traffic calming measures. At all scales, urban form is based on the ‘five minute walking circle’ or between roughly four and five hundred metres, an established average comfortable walking distance which people are most likely willing to walk to the store, bus stop, work, school, day care, etc. (Calthorpe, 1993; Bernick and Cervero, 1997; Beatley and Manning, 1997; Crawford, 2000). The focus of the five-minute walking circle is the transit-stop and basic every day services.

source: www.newurbanism.org

Next Page

Home