I recently attended a very special meeting in Lima, Peru—my birth town. I found out about it from George Nicholas who I saw at SFU on my way to my annual family visit to Lima. I had not planned to do anything "academic" this time around, intending only to revisit the beaches and deserts near the city where I used to do field work decades ago. But I was rather intrigued by the meeting, which was organized by the Culture Commission of the Peruvian Congress and the Ministry of Culture and I managed to get myself invited; one close colleague is now Deputy Minister of Heritage. He is leading a new group of heritage professionals in the region that wish to tackle the shortcomings in policy of the last decades with new approaches towards heritage management—approaches focused on the people who endow heritage with meaning.

Today in Peru, heritage management takes a top-down, enforcement-oriented approach. The state is the full owner of all antiquities, and is responsible for their care. In reality, this system often falls short of its mandate to manage and preserve heritage. This is where the knowledge brought by the foreign contingent at the meeting was needed. These guests addressed heritage management from very different perspectives from that of mainstream Peru. The participation of Christina Luke (Boston University), Larry Coben (Sustainable Preservation Initiative), Denis Byrne (University of Western Sydney) and IPinCH's own Julie Hollowell (Indiana University) and Lynn Meskell (Stanford University) in this "foundational" meeting was quite a breakthrough.

The meeting, Peruvian Cultural Heritage, Heritage for Humanity: Theoretical Foundations for the New Formulations of the Cultural Heritage Law, was attended by invited guests in the field of heritage management, including the staff of the Ministry of Culture (managers and museum directors) and the staff of the Municipality of Lima. Lima is a city built on a river plain, with a very dense population in ancient times, and there are important monuments in the metropolitan area. When the Spanish founded Lima in 1536, they built over the native truncated pyramids; we were probably sitting on top of one of them during the meeting, which was held in one of the chambers of the National Congress. The presentations were witnessed by the guests and by attentive citizens who arrived in waves and sat in the galleries, many of them in their best native dresses, coming from far away.

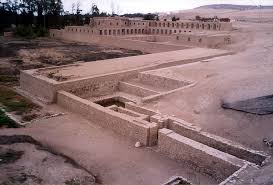

The arguments presented came from two very different fronts: the foreign perspective on heritage, mostly rooted in the idea that native and local communities should be increasingly involved in managing their own heritage; and then the mainstream Peruvian perspective, communicated through presentations on the Huacas de Moche, Caral, and Pachacamac projects. These are the most representative long-term projects in Peru today.

The arguments presented came from two very different fronts: the foreign perspective on heritage, mostly rooted in the idea that native and local communities should be increasingly involved in managing their own heritage; and then the mainstream Peruvian perspective, communicated through presentations on the Huacas de Moche, Caral, and Pachacamac projects. These are the most representative long-term projects in Peru today.

The Huacas de Moche project, now going on 20 years, was conceived under the banner of "culture is a good business." Thoughtful archaeological research and the building of community programs surrounding the monument and the museum were met with economic and social improvements in a semi-rural area of the country. This project's basic funding comes from a private firm and is complemented with other sources. In contrast, the Caral and Pachacamac projects run on public funding, greater than that provided any other sites because of their importance for Peruvian heritage. These two projects, of which Caral had a successful fast-track application to attain World Heritage status in 2009, are managed with a great deal of regional autonomy. They are exemplary projects thanks to the vision of their directors, each with its own character, principles and ways. Indeed, these national projects are examples of Peru’s healthy, albeit eclectic, strategies for cultural heritage management. Interaction with local communities has varied among the projects: there is participation of communities under the direction of the archaeologist, and occasional cases of consultation, but there are not yet cases of community-driven heritage management. The participation of communities in heritage projects, which arguably should lead to self-determination, is not yet established in Peru.

At the meeting, Denis Byrne described his experience working towards new cultural rights for Australian Aborigines in the 1970s, as well as building a management system that strove to include landmarks relevant to native populations ("mapping new dimensions of space"). This long process and its intricacies, Byrne added, have been superseded and new forms of management will be needed in the near future. Today Peru is at the same stage that Australia was in the 1970s, when local communities (and not necessarily "native" ones) began to play a central role in managing heritage. That being said, native communities in Peru have very different ways of relating to their ancestors, different social issues, different concerns, and a distinct social position within society, arguably related to the imperial past.

Christina Luke, speaking on her experience working in cultural affairs at the U.S. State Department, argued that there is much potential in the bilateral agreements signed between Peru and the United States, which Luke believes have been underexploited. Little contact or exchange of knowledge between American and Peruvian institutions has occurred despite the financial and institutional incentives included in the agreements. The new challenges Peru is facing in managing heritage warrant the use of cooperation and knowledge exchange more than ever.

Christina Luke, speaking on her experience working in cultural affairs at the U.S. State Department, argued that there is much potential in the bilateral agreements signed between Peru and the United States, which Luke believes have been underexploited. Little contact or exchange of knowledge between American and Peruvian institutions has occurred despite the financial and institutional incentives included in the agreements. The new challenges Peru is facing in managing heritage warrant the use of cooperation and knowledge exchange more than ever.

Larry Coben presented the initiatives of his group, The Sustainable Preservation Initiative, which has started its first projects in Peru. Each project is developed at a researched archaeological site that has been open to the public and is therefore is subject to new levels of risk. For each site the aim is to create outlets for economic development for women and men interested in creating products that reflect local traditions and skills.

Larry Coben presented the initiatives of his group, The Sustainable Preservation Initiative, which has started its first projects in Peru. Each project is developed at a researched archaeological site that has been open to the public and is therefore is subject to new levels of risk. For each site the aim is to create outlets for economic development for women and men interested in creating products that reflect local traditions and skills.

Lynn Meskell, with her knowledge of the cultural diplomatic arena and dealings with UNESCO, encouraged Peru, now a member of the World Heritage Committee, to lay out meaningful strategies for world cultural heritage, drawing on the national cases that, in their diversity, show the country’s novel management strategies. These strategies could benefit new heritage assets becoming part of the world list. She underlined the necessity for experts in cultural heritage to join in, and to lead and direct the strategic arguments, which are usually in the hands of diplomatic representatives.

Finally, Julie Hollowell, perhaps the most “foreign” in her arguments—a perspective that was much needed in this context—stressed the indivisible character of tangible and intangible heritage and the implications this has for effective heritage management. Peru has laws stating that walls, pots, and pyramids are “heritage,” but has no legislation that protects the virgin forest and it’s importance for local populations as heritage. A new legal framework, argues Julie, should include the means for local populations to claim knowledge and ways of life as the cornerstone of their heritage. In this way, both these populations and their landscape (natural and cultural) could be protected from development, and local groups could define priorities for their future. But it is very challenging for a centralized government to relinquish control and decision making to communities.

There was optimism from both the local and the foreign voices, given the exemplary work underway. In the closing of the seminar, Luis Jaime Castillo, Deputy Minister of Heritage, clearly acknowledged the limitations of state-driven, top-down strategies to manage heritage, especially in curbing looting and trafficking, and in promoting grass-roots heritage awareness. Inspired by the examples and strategies presented at the meeting, Castillo suggested the importance of creating a law in Peru that increases the participation of, and ultimately empowers, local populations, promotes a bottom-up management strategy and introduces new technologies, to preserve Peru’s cultural heritage and enrich its cultural assets.

Photos: the Caral site (Wikipedia); L-R: Julie Hollowell, Luis Armando Muro Ynonan, Denis Byrne, Lynn Meskell and Sonia Guillen, at the Incan Bridge on the road leading to Machu Picchu (Photo: courtesy J. Hollowell); Luis Jaime Castillo (Deputy Minister for Heritage), Lynn Meskell, Denise Pozzi-Escot (Director, Site Museum Pachacamac) and Jose Canziani (Landscape specialist) at the meeting (photo: J. Lizarzaburu); one view of Huacas de Moche (Wikipedia); the Pachacamac site (Wikipedia); Sustainable Preservation Initiative logo (SPI).