November is Native American Heritage Month in the United States and, while many will honor the diverse ancestry and cultural traditions of Native American cultures in appropriate ways, there will undoubtedly be some educators who fall back on classroom lessons involving paper-feather headdresses and skits depicting the first Thanksgiving.

Other stereotypes are perpetuated throughout the year, for example, when Native American names and images are used for school and sports team mascots.

Cultural appropriation, the often-unwelcome “borrowing” of elements from one culture by members of another, encompasses a broad range of issues from identity to cultural oppression. Misappropriation, as George Nicholas reminds us, “isn’t always clear or simple, and is often nuanced or contextual” (2014). At the heart of this issue is often sheer ignorance and, in some cases, overt racism.

By examining the use of Eskimo images, I ask readers to consider whether certain forms of cultural appropriation are more damaging than others. Is there a more acceptable or appropriate way to appropriate? Are some stereotypes really any less harmful?

Top left, one variation of “Mo - the Escanaba Eskymo” mascot (Escanaba Area Public Schools), and above, Escanaba Eskymo mascot on town water tower.

In the town of Escanaba, in Michigan’s Northern Peninsula, a large water tower displays an image of a smiling, cartoon-like “Eskymo” [sic] clad in a parka with the traditional fur ruff typical of the arctic. The local school district newsletter highlights student achievement with the heading of “The Eskymo Way” and younger students are encouraged to join the “Little Mo” Fan Club - the official club of the “Escanaba Eskymos.” But are those children learning anything about real Eskimo cultures and languages?

Where does this stereotype of the smiling Eskimo come from and why has it persisted over time? Various scholars trace these notions of the Eskimo to the earliest expeditions of the North. The Parry Expeditions of 1819, 1821, and 1824, for example, brought a familiarity with Inuit peoples of the central Canadian Arctic. Westerners soon associated all Eskimo peoples with igloos, and this “became the Eskimo of our imagination” (Brody 1987:19). From the early drawings of the famed 1824 Lyon Expedition comes the stereotypic image of an eternally jovial people: “The Eskimo makes his and her appearance with a smile” (Brody 1987:19).

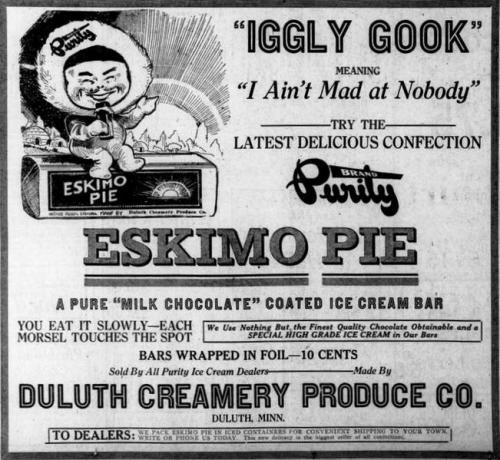

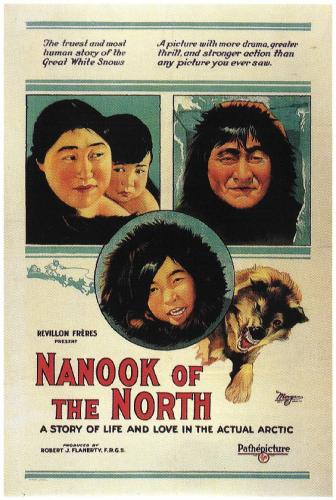

Above, Eskimo Pie Ad - 1922 Duluth Herald (via Wikimedia Commons), and at left, promotional poster for the 1922 documentary Nanook of the North (via Wikimedia Commons).

Above, Eskimo Pie Ad - 1922 Duluth Herald (via Wikimedia Commons), and at left, promotional poster for the 1922 documentary Nanook of the North (via Wikimedia Commons).

Twentieth-century literature and Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s, such as Robert Flaherty’s 1922 silent film Nanook of the North, continued to cast Eskimo peoples as passive, peaceful characters set against a harsh climate.

In sharp contrast are images of North American Indian groups as “hostile” and war-like (Brody 1987), stereotypes that Hollywood reinforced through popular Western “Cowboys and Indians” films.

Is it easier to see the harm this kind of stereotype causes as opposed to the smiling Eskimo? Both are inaccurate and harmful to members of those groups, as well as to students who aren’t taught about the real cultures and languages behind the appropriated images. In fact, most Eskimo groups in Alaska regularly warred with neighboring Eskimo and Athabascan groups (Burch 1998): “The nonviolent character of Eskimo social interaction has been emphasized at the expense of the violence and warfare that are a real part of their history and tradition” (Fienup-Riordan 1994: 146). A history of warfare is predominant in the local folklore of Eskimo communities. On the Bering Sea coast, in the Yup’ik Eskimo village where I have worked for more than two decades, stories not only recount widespread warfare but also specifically mention which neighboring villages were enemies.

A history of colonization is not unique to North America, but the practice of deriving school and sports team names, imagery, and mascots from Indigenous peoples—and the debates that ensue—seem to be more prominent in Canada and the United States (see Richard King 2010).

Adding to the complexity of these debates, there is no agreement as to what constitutes appropriate or inappropriate usage when policy is established. Author Glenn George points to the inconsistency with which “the rules” apply “calling a sports team the ‘Braves’ may sometimes create a hostile and abusive environment. Other times, the name is acceptable. Specific tribal names have been permitted with approval, while generic names like ‘Warriors’ and ‘Indians’ have been rejected. Feathers are permitted in North Carolina, but not Virginia” (George 2006: 90).

More than twenty years ago the Alaska Legislature proposed a resolution urging Alaska Airlines to retain their “iconic” logo (said to be the face of an Inupiaq Eskimo man, Chester Seveck, who was a well-known reindeer herder and Eskimo dancer). The Los Angeles Times reported in 1988 that “The parka-hooded, smiling Eskimo face emblazoned on the tail of Alaska Airlines planes may soon be replaced by a new emblem, and some Alaskans are incensed.”

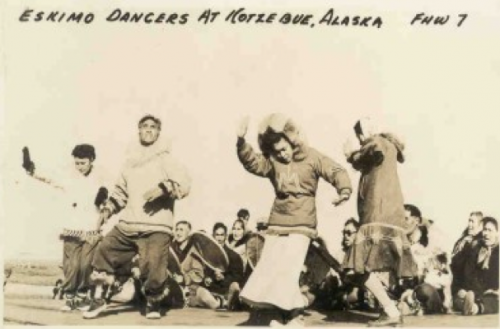

Left: Alaska Airlines, Ken Fielding [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons; Right: Chester Seivek dancing (at left, via Historical Photographs of Kotzebue Alaska).

In Canada, some are calling to have the Edmonton Eskimos hockey team’s name changed, arguing that the name has no cultural significance in Cree territory. As one blogger wrote, “We might as well call ourselves the Edmonton Navajo or the Edmonton Aztecs,” but then went on to say “the Eskimos name isn’t a big issue in the city because the team doesn’t have an offensive logo to go along with it ... I think the difference when you compare the Eskimos to say the Cleveland Indians or the Washington Redskins is that… we don’t have a caricature or cartoon character on our jerseys" (CBC News, 2014). Both of these examples highlight the tensions of what Maori scholar Deidre Brown, calls “the boundary between appropriateness and offensiveness” (2013).

Less than two years ago, the Michigan Department of Civil Rights (MDCR) filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights (OCR), urging the federal government to prohibit the use of “American Indian mascots, names, nicknames, slogans, chants and/or imagery.” The foundation of this important initiative was based on the argument that this “negatively impacts student learning, creating an unequal learning environment in violation of Article VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964”:

Continued use of American Indian mascots, names, nicknames, logos, slogans, chants and/or other imagery creates a hostile environment and denies equal rights to all current and future American Indian students and must therefore cease.

The elimination of Indigenous names and use of mascots in local schools has gained momentum, but this change requires individual communities to become aware of the issues.

“Tribal leaders, parents, and students have consistently raised concerns about Native student environment issues; including bullying, school discipline, stereotypes, as well as harmful imagery and symbolism” (The White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education, 2015). When I asked why the Escanaba “Eskymos” weren’t listed on the action, the Director of Law and Policy for the Michigan Department of Civil Rights responded that, while the group had discussed whether or not to include the “Eskymos,” they “feared that the non-violent stereotypes and the 'cute' images associated with Eskimos would make it easier” for opponents to diminish or trivialize the arguments put forth [personal communication, September 3, 2015].

“Tribal leaders, parents, and students have consistently raised concerns about Native student environment issues; including bullying, school discipline, stereotypes, as well as harmful imagery and symbolism” (The White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education, 2015). When I asked why the Escanaba “Eskymos” weren’t listed on the action, the Director of Law and Policy for the Michigan Department of Civil Rights responded that, while the group had discussed whether or not to include the “Eskymos,” they “feared that the non-violent stereotypes and the 'cute' images associated with Eskimos would make it easier” for opponents to diminish or trivialize the arguments put forth [personal communication, September 3, 2015].

At right, high school “chief” mascot (via Michigan Department of Civil Rights 2013, Appendix B).

More than 3,000 miles from that water tower in Michigan, on the Bering Sea Coast in what is actually Eskimo territory, a local high school and its sports teams proudly display another Inuit logo. This logo, a warrior, depicts the cultural past of the very group using that logo. Unlike the cute, smiling “Eskymo” of Escanaba, this usage depicts Eskimo people of that region accurately. Their ancestors were warriors, and unlike the smiling Eskimo, this usage isn’t stereotypic.

Above, Hooper Bay Warrior fans celebrate (Erik Hill via Alaska Dispatch News, used with permission).

The real issue here may not be the need for prohibiting the use of any or all cultural groups as mascots, but rather to initiate a standard practice of asking who is adopting the image and why. We need to tease out the degrees of complexity in the processes of cultural appropriation, acknowledging that while usage may not be deemed “offensive,” it is nonetheless inappropriate. More importantly, we need to acknowledge that all stereotypes are hostile and abusive because they depict another group in an inaccurate light.

References Cited

- Brody, Hugh. 1987. Living Arctic: Hunters of the Canadian North. Douglas and McIntyre , Vancouver (in collaboration with the British Museum and Indigenous Survival International).

- Brown, Deidre. 2013. Traditional Identity: the Commodification of New Zealand Maori Imagery. IPinCH Cultural Commodification, Indigenous Peoples & Self-Determination Public Symposium, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, May 2.

- Burch, Ernest S. Jr. 1998. The Inupiaq Eskimo Nations of Northwest Alaska. University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks.

- CBC News. 2014. Should the Edmonton Eskimos change their name? Accessed August 22, 2015.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 1994. Eskimo Essays. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

- George, Glenn B. 2006. “Playing Cowboys and Indians.” Faculty Publications. Paper 855. College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans.

- King, Richard C. 2010. The Native American Mascot Controversy: A Handbook. Washington State University Press, Pullman.

- Los Angeles Times. 1988. Airline's Plan to Junk Eskimo Logo Stirs Up Some Alaskans. Accessed October 15, 2015.

- Michigan Department of Civil Rights (MDCR). 2013. Continued Use of American Indian Mascots Hurts Student Achievement. Complaint filed with the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights.

- Nicholas, George. 2014. Appropriation (?) of the Month: The Midterm Exam. IPinCH Blog.

- The White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education. 2015. The Native Student Environment Initiative. Accessed September 3, 2015.

Further Reading

- Asakak Seveck, Chester. 1973. Longest Reindeer Herder: A fascinating true life story of an Alaskan Eskimo covering the period from 1890 to 1973. Alaskool.org.

- Eberhardt, Jennifer L. and Susan T. Fiske. 1998. Confronting Racism: The Problem and the Response. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Egan, Brian. 2014. Appropriation (?) of the Month: Seven lessons from the Native American sports mascot controversy. IPinCH Blog.

- Kaplan, Lawrence. Inuit or Eskimo: Which name to use? Alaska Native Language Center.

- Keene, Adrienne. 2015. Exploring Indigenous Intellectual Property through Mascots, Fashion, and Tribal Names. IPinCH Blog.

- Roth, Solen. 2015. Appropriation (?) of the Month: Differentiating "Northwest Coast-style" from Northwest Coast art and design. IPinCH Blog.

- Udy, Vanessa. 2015. Teepees and Trademarks: Aboriginal Peoples, Stereotypes and Intellectual Property. IPinCH Videos.

Holly Cusack-McVeigh is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Museum Studies & Public Scholar of Collections and Community Curation at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, and an IPinCH Associate.

Our Appropriation (?) of the Month features, written by IPinCH team members, explore the fine line between 'cultural appreciation' and 'cultural appropriation.'