|

| |

|

Let's play "Major Acquistion" |

| Now we come to the fun part. You

obviously love books or you wouldn't have come this direction in your life and education,

nor have taken this course. So in the spirit of book-lovers, this game will take on

a decidedly bibliophilic character. Over the course of the history of the written

word, starting around 3500 BC, there have been grand libraries that have housed priceless

collections. It is a tragedy that many of the early libraries didn't survive, mostly

due to fire, but here and there, a few manuscripts escaped destruction. For a tale

of what befell the ancient libraries, read here: Ancient Libraries

Today, however, several of these books or clay tablets are now available online, either

scanned or reproduced from the original. |

| First of all, let's play, "What if..." What if you could build the most wonderful library in

the world and house some of the most outstanding books that have survived the ravages of

time?

What if it were possible to

acquire these books... for a price?

What if the price was just

answering a few questions... |

|

| (Okay, so it's a trick question!) |

Ceiling of the old reading room of the British Library, now

part of the Great Court of the British Musuem |

| Here are the rules

of the game: At the end of your readings each week you will

be posed with a question. Based on what you have read, jot down and answer and bring

it to class. We will discuss the question and then I will e-mail the answer to the

class afterwards. If you have come up with a good response, you will be able to add

the "book treasure" of the week to your library.

As always, there is no perfectly correct answer, but there are

good and better answers. So have a look at this week's question (at bottom) when you

are ready, and try your luck!

But first, here is the PRIZE for Week 2: |

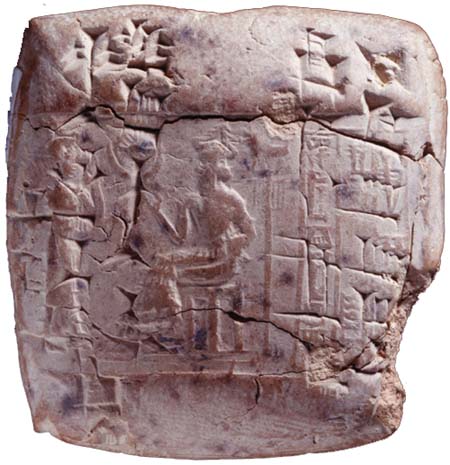

#1 The oldest existing

piece of literature:

|

|

| Manuscript( also here abbreviated as

"MS"): Sumerian on clay, Sumer, ca. 2600 BC, Commentary: The present Early Dynastic tablet is one of a few that

represent the earliest literature in the world. Only 4 groups of texts are known from the

dawn of literature: The Shuruppak instructions, The Kesh temple hymn, The hymn to Inanna

as war goddess (MS 3211), and various incantations (see MS 4549). The

instructions are addressed by the ante-diluvian ruler Shuruppak, to his son Ziusudra, who

was the Sumerian Noah, cf. MS 3026, the Sumerian Flood

Story, and MS 2950,

Atra- Hasis, the Old Babylonian Flood Story. The Shuruppak instructions can be said to be

the Sumerian forerunner of the 10 Commandments and some of the Proverbs of the Bible: Line

50: Do not curse with powerful means (3rd Commandment); lines 28: Do not kill (6th

Commandment); line 33-34: Do not laugh with or sit alone in a chamber with a girl that is

married (7th Commandment); lines 28-31: Do not steal or commit robbery (8th Commandment);

and line 36: Do not spit out lies (9th Commandment).

(Please see credits for ancient manuscripts at bottom) |

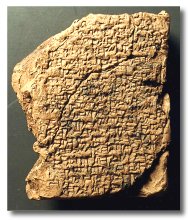

#2 Cuneiform Tablet

In the late fourth and third milleniums BC, the Sumerians began

to develop a writing system called "cuneiform" ("wedge-shaped"),

written on wet clay with a sharpened stick, or stylus. At first the Sumerians used a

series of pictures ("pictograms") to record information having to do with

business and administration, but went on to develop a system of symbols that stood for

ideas and later sounds (usually syllables). In the later stages of Sumerian writing there

were about 600 signs that were used on a regular basis.

The language that the Sumerians used is not related to any other

language we know, and it gradually ceased to be a spoken language. The writing system,

however, was adopted by people speaking a Semitic language called Akkadian, and continued

to be used by a number of peoples up until the 1st century B.C.E. Both the Babylonians and

Assyrians, who spoke dialects of Akkadian, used the cuneiform signs, writing not only in

their own languages, but sometimes in Sumerian as well. Sumerian had become the language

of literature and scholarship, somewhat like Latin up until fairly recently.

Cuneiform tablets have also been found in Eblaite (a Semitic

language from northern Syria), Elamite (from the area of modern Iran), Hittite (an

Indo-European language spoken in ancient Turkey), and other languages throughout the

ancient Near East.

The tablet illustrated here is a business document with a seal

impression. Seal impressions are somewhat like signatures, in that they identify the

person involved in the business transaction recorded on the tablet. While most of the

tablets that have been found are such things as contracts, sales receipts, and tax

records, a number of very important literary texts have been found as well, such as the

Epic of Gilgamesh and the Code of Hammurabi. |

|

#3 FLOOD STORY

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia,

19th-18th c. BC, Context: For 5 of the 6 Sumerian forerunners of the

Gilgamesh Epic, see MSS 2652/1-2,

2887, 3026, 3027

and 3361.

Commentary: Mankind's oldest reference to the Deluge, together with 1/3 tablet

in Philadelphia, the only other tablet bearing this story in Sumerian. The tablets share

several lines from the beginning of the Flood story, but the present tablet also offers

new lines and textual variants. Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah, is here described as

"the priest of Enki", which is new information.

The Sumerian Flood story is one of the 6 forerunners to the Old Babylonian Gilgamesh

Epic, the source for the Old Babylonian myth Atra-Hasis, and for the Biblical account of

the Flood (Genesis 6:5-9:29), written down several hundred years later.

According to British Museum, their Neo Babylonian tablet with the Flood story as a part

of Gilgamesh, is perhaps the most famous tablet in the world. The present tablet is over

1000 years older. |

| THE QUESTION: In philosophy, we ask: What is knowledge? In educational

theory, we ask: What is the aim of education? How shall we teach?

How do you think Plato and Homer might answer the last two

questions? |

|