P Perceiving page |

|

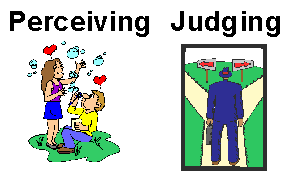

| The Perceiving type prefers to embrace life in a spontaneous, adventurous manner, gathering information from as many sources as possible so as to understand and fit herself to events. The P wants to experience life as it happens. Ever curious, the P would choose to put off making decisions until she feels she has explored all alternatives. Ps enjoy a flexible mode of living that challenges and offers pleasure. Spontaneity and surprise upset Js, but not Ps. The process is the main goal, not the product and other types find that Ps often begin more projects than they can see to completion. Other adjectives for Ps: adaptive, non-judgemental, open-minded, irresponsible, easy-going, indecisive, shallow, free spirit, messy, nosey, eager and risk-taker. Ways to strengthen the P type: plan backwards from goals to develop good time management skills, use a calendar, give yourself extra time to complete projects, limit the time for information gathering, cut out less important tasks to allow time for finishing important ones. |

|

|

|

Now in my Perceiving function, I'd like to look further into type and relate it to some of my studies in literature and aesthetics. |

|

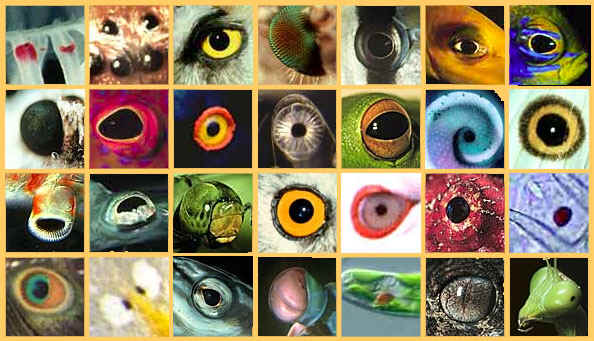

Eye Image Array courtesy of BioMEDIA ASSOCIATES - http://ebiomedia.com URL - http://ebiomedia.com/gall/eyes/eye1.html |

BUT WHAT ABOUT AESTHETICS?

As mentioned earlier, there are many groups opposed to employing Jungian typology

or the MBTI because they fear it may encourage people to see other human beings in terms

of stereotypes. Many people also do not like

the idea of thinking of themselves as falling neatly into categories; they feel human

beings are much more complex than belonging to one of only sixteen types. At this point it might be worthwhile to remind

them that this is “theory” and not a practical resource meant for application in

the classroom or anywhere else. As Dr.

Mamchur and others have said, typology is a tool, something that can aid us in

finding a starting point where we may begin to conceive of the diversity of personality in

human beings. The MBTI categories are

acknowledged as very broad designations and only indicate patterns of preferences

in how we perceive the world and judge situations in order to make decisions. The artists themselves are the most

resistant to applying any kind of a science or system in relation to creativity and

especially the arts. I would agree that the

artist needs absolute freedom when approaching her work and is doomed if she tries to

hitch her artistic skills to a framework as she begins to create. Aesthetics and the creative process, by the nature

of their being, cannot accept any limiting or overlaying guidelines. As Collingwood puts it, how can a writer know what

she’s going to write until she’s written it?

It is the quintessential organic process and the artist only finds out what

she is going to create as she is in the throes of creating it. Personally, I’ve struggled with the

idea that typology might be a better way to look at personalities. I have felt myself go through distinct stages. First, being very curious about the qualities of

the four preferences, pairs and sixteen types and have delighted in class when we point

out examples of “acting our type”. Second,

I felt myself enter a “fatigue” stage, where I became tired of thinking of

people along the lines of type and wanted to go back to my old, more “natural”

way of seeing people. Third, after two years

of not working with type and deciding to enroll in this course which would be fully

dedicated to type, I felt both intrigued and cautious – intrigued because I had done

a lot more fiction writing in the meantime and wanted to improve my ability to create

literary characters, but cautious because I had become much more aware of the organic

nature of writing and had settled on my own method of writing, which I realized had been

evolving ever since childhood. Lastly, the

stage which I am in now (!) seems to be more in harmony with Hegelian logic: thesis + antithesis = synthesis. That is, I see the value of type plus its negative

aspects or limitations and yet I can use it as a tool along with my other tools, so that I

take from type what I want and use it to help my writing in the way I choose. Mainly the benefit I gain from using

typology in writing is not in the creative process, but in the editing process. After I have been free to let my imagination roam

and begun to gather ideas, after I’ve scratched out a first draft and played with the

characters and conflicts until something begins to coalesce, and not until I’ve got a

solid piece of work – then I am able to isolate my characters and compare their

behavior to the established behavior patterns of the functions. I remind myself that some characters are hard to

type and not all will need to fit into the sixteen types.

But perhaps typology is most helpful in the editing stage when I look at two

characters who are in conflict. Often it is

when functions are opposed that more of their differences can be brought out in high

relief. Knowing what their shadows will be in

crisis also helps determine their behavior at the climax.

Finally, I feel that learning about type

helps me most as a writer in terms of self-development.

Being more aware of my own type can direct me to focus on my weaker areas. For example, as a dominant N, I know that I should

make a conscious effort to take the time to add enough detail to my writing, especially to

take care about writing in more scenic time or including more sensuous description. This has often been mentioned in feedback from

other writers, and knowing now about my type, this makes perfect sense. There is one area of type I’ve been

saving for last and that is the Shadow. But

before I cover that area, I’d like to return to the idea of aesthetics in more

detail. Many thinkers have written about this

subject as it relates to the functions, in particular thinking and feeling, and I would

like to bring them into the discussion now.

(Barber,

April 2005)

Art is often defined simply as “expression”. Lyas (103) qualifies that by emphasizing it is the degree of expression. Within that, there are two kinds of expression, ordinary and artistic. The latter must have two qualities to render it art. First, “sufficiency”, wherein the work has a greater intensity and range than the ordinary, and second, a “necessity”. It is not just the sound of birds singing that makes music, but a complex kind of making of sounds. And in this, the artist’s personality comes through. (98-102). Art is expression then, but we must also understand how it is expressed. And we might add that art is powerful because of the expressive significance of representation. (56). All of these ideas come under the umbrella term aesthetics. A somewhat slippery word, it refers to a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature and perception of what is beautiful, and includes taste or the appreciation of beauty. Here we are most concerned with aestheticism, the idea that beauty may be the basic principle from which all other principles, especially moral principles, are derived. Abbs (3) states that the aesthetic is a mode of intelligence. Just as a deductive method of conceptual thinking is developed through logic, mathematics, dialectical and analytical philosophy, the aesthetic uses not concepts but “percepts” of sensory experience. The arts become symbolic forms for what they wish to communicate. There is a continuum here, a sliding scale between sensation and feeling, of sensory experience and sensibility. When we touch an object, we have a perceptual experience, while to be touched is to be moved emotionally. We can say then that the aesthetic includes both the perceptual and the affective. Growing in aesthetic intelligence therefore deals with the development of sensation and feeling into what adds up to be a whole greater than its parts, a “sensibility”. (4). The point we are leading up to is that aesthetic intelligence, when defined in this way, is particular to the arts. It is true, that although there can be feelings of beauty in response to a scientific discovery or a mathematical proof, what I want to focus on, here and in this thesis, is a method of responding that is inherent in human life and one that can only be accessed through senses and feelings. It is not so much the actual sensation that is valued but the apprehension that derives from it. (6). Therefore, returning to Abbs’s (7) definition, the artist can be said to be a “perceptual philosopher”, one who seeks through the symbolic ordering of her sensations a means to gain understanding of the human experience. It was Kant who put aesthetics at the center of philosophy. (Scruton 26). In the Critique of Judgment, Kant places the aesthetic experience in a similar category as the religious experience by suggesting it is the former and not the latter that is the archetype of revelation. Specifically, what he is saying is that the aesthetic experience is able to reveal the sense of the world. How does this happen? Simply, in the presence of beauty an individual senses the purposiveness and intelligibility in the things around him. This beauty may be highly subjective to the individual or it may be his recognition of what is beautiful based on what has been culturally transmitted to him. Either way, when we apprehend the sublime, we feel as though we can see beyond the world to something overwhelming, ineffable and yet strangely grounded. Scruton (26) states that formerly it was the traditional concern of theology to provide a greater meaning of the world, but even before Kant, this faculty which has beauty as its goal, was the same thing as aesthetic contemplation. Scruton further states that human beings have always had “intimations of the transcendental”, either personal or cultural, as a quality of being human. None of this can be argued fully with reason. Language has its limits here. As we try to grope our way between thought and emotion we become intuitive rather than rational or analytical. This is because we are able to grasp the idea of the transcendental without being able to verbalize it. Ultimately we know nothing of the transcendental. But we feel it and it is in this feeling of beauty that we sense truth. (26). To take this idea further, we could say that when we become aware of the beauty in a literary work, its content begins to feel true. And simultaneously, as we start to become conscious of the literary “world” presented to us, certain truths about that world begin to emerge. We might even believe that these truths make perfect sense, within that world. This is remarkably so in the case of inspired religious texts, where apprehension of these works’ beauty, and therefore feelings of truth, inexplicably begins to intimate at meaning. This may seem to be a non sequitur where beautiful but different works of art both present the “truth” despite the contradictory nature of their content. Murdoch (8) explains that unlike philosophy and science, literature asks us “to submit oneself to criteria outside oneself; (the author) tries to say something that is impersonally true”. I feel the answer lies somehow closer to Aristotle’s concept, that just as we learn to value individuals within their qualitatively distinct situations, we must also consider works of literature within the contexts of their unique “worlds” and therefore examine the truth found therein. Therefore, there may be no absolute truths to be found in any one work of literature in relation to the “real” world; too much depends upon the circumstances presented in the story and also on the life, experiences and views of the reader, or, even more specifically, what that reader believes to be true, both subjectively as well as culturally, religiously, etc. Even scientific truths have been proven false since the time they were included in classical works. What we can say with some certainty is that taken collectively, there are “norms” of morality that emerge from a survey of the literary canon, which may point at “general truths”. Returning now to Kant’s third Critique, we see the significance of the shift from religion to philosophy, specifically Christianity to the Enlightenment, which was to bring ethics and aesthetics to the forefront. Echoing the Copernican revolution in science, Kant believes the mind gives structure to the world and not the other way round. What occurs, he says, is that we struggle to organize the bombardment of random stimuli into perceived objects, which is done by our imagination. The creation of conceptual categories is done through understanding. (Lyas 25). What we have when the mind plays back and forth between imagination and understanding is aesthetic delight or rapture. (31). This takes place in a state of disinterestedness, when there is no personal motivation for assigning value. (28). It is often called an aesthetic attitude, or a possession of a psychic distance, that allows the mind to roam with controlled imagination. The freedom that ensues releases us from the numbness of our daily lives. (31). This is why we are so attracted to art and why it is so powerful to us. (19). We stand in awe before representation and tend to cherish those works by gifted artists who are able to capture a part of life and truth. (38). Through its unique blend of form and content, then, art can remind us of our humanity in new and fresh ways and confirm our connectedness to others. It says a great deal about the permanence of values and conceptions of human nature that startles us when we realize we can still understand Homer and Aeschylus. Literature is the main vehicle, as it was in Homer’s time, for this wide-ranging understanding. We would not want to be cut off from this vast encyclopedia of the past, in terms of its art, history or moral viewpoints. (Murdoch 25).

Collingwood and The Principles of Art Collingwood (15) goes to great lengths to define what art is not, and why. Art, he tells us, is not craft, mainly because it cannot have an end in mind when the artist is at the beginning. How does the author know what a story is about until she has written it? Art is not representational, in that it does not copy another work of art or real life situations. Imitation is impossible in storytelling anyway because if the writer changes one thing it becomes a completely different work of art. A true imitation would be the identical story. Further, an author trying to recreate a “real” event from life would find it impossible to include every visual detail, every personality trait and point of view without sacrificing the “story”. Plato believed all art was representational and therefore too removed from reality to convey the truth. But Collingwood disagrees; he says art may be representational but what makes it a work of art proper is another thing – what is missing is the emotional aspect, as we shall see. We might, however, acknowledge that Plato was on to something, and although he did not have the concept of aesthetics in his day, he criticized art in a way that echoes the public’s view of art, which tends to see art as mere entertainment or distraction. It is well known that Plato banished the poets from his ideal republic because he objected to the emotion that was stimulated by art, which in his view clouded the rational mind. What may have been further behind this is that in Plato’s era there was a shift in ancient Greece’s values. As Greece began to dominate the region in ideologies, religion, philosophy, politics and economics, the religious-based art of pre-Socratic times began to evolve from what Collingwood terms “magical art”, or art with a purpose, to one of a more trivial nature, “amusement art”. Whereas in the earlier times people used art to instill religious values, good behavior and noble deeds, now people were attending theatre performances to be entertained and to let off tensions through tragedy or comedy. Aristotle, on the other hand, defended Greek drama as being useful, and maintained that by arousing dangerous emotions in a controlled setting, the play was facilitating “catharsis”, or release of pent up emotions, which served a purpose in society. Plato might have disagreed, saying the opposite is more likely to occur just as we see in our own times with “copycat” crimes. The teenage boys who gunned down their fellow students at Columbine had supposedly just watched an extreme example of glorified violence in The Matrix. Art then for the ancient Greeks was “craft”, created with an end in mind. The aim was to entertain the masses and Plato objected most to its irrational, trivial nature. Plato wrote the Republic to warn of the dangers facing a society that is given over more and more to amusement, and also to the citizens who feel because there is less meaning in life they must reach out for distractions. He went as far as to say that the percentage of a society’s citizens who pursue pleasure is directly related to the health of its civilization. If this conception of art is accurate, we may well ask what this bodes for our times. Plato’s solution was to remove art in order to promote truth and rationality in the ideal republic. We must hold close to Aristotle’s view of ethics to find more appreciation of the arts in terms of its virtue, justice, pleasure, honor and the “good” it can bring. Before we move on, however, one last but important distinction must be made here between Plato’s condemnation of amusement art and the perfect refutation of that view in the example of hybridization in Shakespeare. Here we find the answer to Plato’s blanket dismissal. Keenly aware that his livelihood depended on enthralling the masses, Shakespeare nonetheless applied his unique abilities to raising art above amusement to “art proper”, by adding emotional complexity and rational contemplation on multiple levels of understanding. His plays appealed to the groundlings up to the royal boxes and here we have proof that art can be many things at once. Returning to our definition of art, which Collingwood has labeled not as craft, magic or amusement, we must now ask, what is “art proper”? Genuine art, Collingwood tell us, is about expressing emotion. The act of expressing it, in the process of making the work, is an exploration of the artist’s emotion. It cannot be crafted because the artist does not yet know what the emotion is because she has not yet expressed it. Along with this is the idea that it cannot be technique; if a writer describes an emotion, it is no longer expressed. The beginning writer is exhorted: Show! Don’t tell. Many authors have slipped in their art because they were lazy or somehow believed the “message” would not get through. This is the case at the end of Crime and Punishment, when Dostoyevsky cannot refrain from resorting to direct statements about the character’s situation and the implications for humanity. Ironically, he must have felt the whole novel previous to this did not say the same thing and the poet in Dostoyevsky yielded to the philosopher. (Cutler 3). As a result, the astute reader feels hit over the head with the redundancy and the imaginative aesthetic experience is greatly diminished. Coleridge may have said it best when he claimed to identify a poet by the fact that as the poet was expressing his emotions he was enabling us to express our own. It may be the case that not all artists are willing to do the hard labor that is required to create art proper. For it is true that it is much more difficult to read, and therefore write, literature proper. Non-fiction not only tells us what to think, it tells us how to think about its subject. All the hard work is done for us in reading non-fiction. It is presented in a clear, rational, journalistic style and leaves no doubt to meaning – that is, what it means to the author. The authorial voice is firmly in place. If we choose, we never have to search for our own meaning. But, we can relax; just accept what we read as the truth. Somebody else’s truth. In sharp contrast, literature that challenges us to find out who we are and what we think helps us in the world. This is the essence of the aesthetic experience. Put simply, good art is good for us. Putting Feeling to Work in Aesthetics

Perhaps we need to go a bit deeper beyond the meaning of art proper to the artist. Who must the artist be in order to produce a significant work of art? Collingwood (279) cites the necessity of deep and powerful emotions, and Coleridge describes the poet as someone who must feel deeply before he can think deeply. But the artist is not the “genius” of the Romantic era who is endowed with special powers, or Plato’s concept of the “mad” or irrational poet who serves as a conduit of the gods. Collingwood (119) says the artist is one who solves the problem of how to express emotion and thereby leads the reader to his own expression. In The Principles of Art, Collingwood painstakingly outlines his theory of the role emotions play in our aesthetic response. He suggests that phenomenon bombard us with stimuli which reach us through the senses. Each “sensum” we receive comes with an emotional charge, which are inseparable at the psychical level, below our awareness. As our attention shifts and we notice a particular sensum-emotion, we become conscious of receiving it. For example, waves of sound move into our ear as mere “noise”, simultaneously high-pitched and tense, a sensum and an emotion. When we become conscious of it, our field of awareness splits into hearing the sound, noticing it and then naming it as “high-pitched and tense” as we seek to dominate it as an idea in our imagination. Our attention now focuses on this one thing in exclusion to others. Here in the conscious imagination we decide what we feel about it, then begin to make connections or relations with other ideas. It now moves into the realm of the intellect. But this is not all of it. When a writer creates a story, it may only exist in her mind. (Collingwood 131). If she puts it down on paper, it is only black symbols on a white page, or groups of letters strung across paper. The artist’s goal is to bring the story into existence as she feels and sees in her head. The words on the page are at this point only the means by which the reader, if he reads intelligently, can reconstruct for himself the story that existed in the author’s mind at the time of writing. (139). For it is true that unless the reader begins to “hear” the words, even silently inside his head, take them as his own, respond to the rhyme and rhythm, pattern and intonation, as well as falling in with the author’s particular use of language and begin to recognize the effect of this language to reproduce emotion, then the work will remain nothing but ink prints on white paper. However, if the author has through symbol, language and sound put an emotional experience in motion, and if the reader’s imagination is able to fill in all the spaces around these symbols to flesh out the experience, then the mind’s eye of the reader begins to see a whole world there, which adds up to much more that ink or words. It is these very areas of indeterminacy that are the most fundamental elements of aesthetic response. The gaps invite engagement and participation. (Iser). But again, we have to make the effort. If the author evokes enough vivid points of reference, say, in describing the rumbling of canons along a gutted road, cries coming from the trees and smoke reddening an already bloody sunset, then a powerful emotional response begins to coalesce, as well as a fuller picture of a “world” beyond what we are told. This is how we can feel we have been present at the Battle of Borodino; the experience of reading War and Peace is that immediate. Tolstoy has provided the first part; that of translating his own aesthetic experience into words that would make a sensum-emotional impression upon our consciousness so that we as readers could imaginatively reconstruct it in our own minds. This is not to say that we focus only on the sensuous part and put our imagination to work; we are able to find impressions because we are utilizing our imaginative powers to discover what the author would like to reveal. Collingwood (151) describes this as an “imaginary experience of total activity which we find (in the work of art) because (the artist) had put it there”. “The work of art proper is a total activity which the person enjoying it apprehends, or is conscious of by the use of his imagination”. The artist is not aiming to produce a preconceived emotional effect in the reader; the author is exploring her own emotions (122). The only aim at the beginning of creating a work is to discover emotions in herself as related to a subject, characters, or situation, etc., that she was previously unaware of. By sharing with the reader the process by which she discovered them she enables the reader to a) witness the discovery, and b) enable the reader to make a similar discovery in himself. Again, this is not done by direct statements in literature or by telling the reader what to think. This is key to understanding how ethics and aesthetics are united in art.

Truth in the Artist

It is often said that a writer writes because she must. Something within her compels her to write a certain story. She is in need of exploring a particular set of circumstances, and of all the possibilities, she has chosen this one. Collingwood (287) says that “each (work of art) is created to express an emotion arising within (the artist) at that point in his life and no other…and if the generative act which produces that utterance is an act of consciousness, and hence an act of thought, it follows that this utterance, so far from being indifferent to the distinction between truth and falsehood, is necessarily an attempt to state the truth. So far as the utterance is a good work of art, it is a true utterance; its artistic merit and its truth are the same thing.” It is precisely in this struggle to discover and convey deep, authentic emotion that leads to creating significant art, and holds the potential of being called “good” art. Collingwood (291) says, “the artist is a person who comes to know himself, to know his emotion…this knowing of himself is a making of himself.” In other words, the work that she creates at this particular time is personally true for this artist. To define a thing implies there could be a good thing of that kind (280). “To call things (such as art) good and bad is to imply success and failure.” For Collingwood, it follows then that a work of art may be either good or bad, but a bad work of art might be due to an unsuccessful attempt at becoming conscious of a given emotion. If this fault lies within the artist, it could be construed in a number of ways. The writer may weakly express an emotion, as we’ve said, and just “tell it”. Or, she could avoid it altogether, misread it, or blunder through it. But in the way it relates to our problem, it seems to be a case of disguising it from herself. This might be caused by denying to herself that it exists, or that it is not her own emotion but coming from something else. Collingwood (282) says this choice occurs in the level of awareness just before consciousness -- earlier would be too soon for awareness; later would be to tell oneself a lie, since if she were conscious of the truth she could not deceive herself about it. Therefore, it is on the border of the psychical level and conscious level. “It is the malperformance of the act which converts what is merely psychical (impression) into what is conscious (idea)” which leads to a ‘corruption of consciousness’”. Often this very corruption of consciousness, caused by a failure to express an emotion, is what prevents the writer from realizing whether the emotion has been expressed or not. It is a veritable circle – a bad artist is a bad judge of her own art (283). But Collingwood generously states that no one’s consciousness is completely corrupted – it is often partial or temporary – and that is why at other times the writer is able to judge the success of her own work and realize when it is not working. In fact, most experienced authors are constantly on guard to eliminate these corruptions. What is of danger, as we have implied above, is when instead of expressing emotions, the artist disowns them or intentionally avoids facing the truth of them. If the author wishes to remain ignorant of emotions that terrify or disgust, for example, then this is not only bad art but damaging art. (284). How this occurs we shall show in later sections. The Good in the Artist

If the artist has two goals, first to become

more in touch with a greater range and depth of emotions (imagination), and secondly, to

improve her ability to express those emotions through her art (skills), then how might she

go about this? If “good” art is

expressing emotions successfully, then does it follow that a “good” writer would

be more successful at discovering emotions within herself?

How would someone improve their ability to discover emotions? I think we might say it comes back to the idea of

being attentive to the emotional truth within oneself and working hard to avoid a

corruption of consciousness. But we are still

too limited in ourselves and our lives to have experiences which might lead to discovering

a greater range and depth of emotion. Granted,

some authors have made careers of going over and over the same territory, ever deepening

their own understanding of their obsessions, such as Fitzgerald and Munro. But even they had to have exposure to other forms

of these experiences and emotions in order to grow. The

obvious answer here is to read other successful literature.

One of the main ways that

literature is unique, as Aristotle says, is that it ushers us into a larger life; without

it we have not lived enough to escape the confines of our parochial existence. (Nussbaum 47).

Also, because we engage with literature in a disinterested manner, we are

able to get close enough to watch and begin to understand the “other”. There is irony here; while recognizing the

strangeness of others, literature invites us to withhold judgment until we have discerned

the separate and qualitative uniqueness of other beings.

After we have opened ourselves up, we have a chance to see ourselves in

them. It allows us to perceive beyond

ourselves. “Then the

‘otherness’ which enters into us makes us ‘other’”. (Steiner 188).

The challenge is to let go ourselves in order to become something better, as

writers, readers or human beings. As the author becomes more adept at determining the

truth in emotions, she more easily discerns what is “good” art. But how is the artist to find what is good in

herself? There is no formula for developing

the virtues of being a writer, but the artist can subject herself to self-examination to

determine the truthfulness of her consciousness. And

yet writing is such a solitary act. A writer

needs readers, but even then there is little direct response in the same way that an actor

has an audience. For writers it is important

to have the feedback of other writers, for support as well as criticism. The literary critic comes too late for the author;

it is during the process of writing that a response is needed. The place where much valuable collaboration occurs

is in the creative writing classroom.

The Author’s “True” Personality (The Only Author We Can Really Know) In literature, the identification of the

“posited” author is most critical to student learning. By “posited” I mean not a character in

the story who might seem to represent the author’s viewpoint, or even the narrator,

who appears to be leading the reader through the story and pointing at things to notice. Nor do I mean the historical author, the man

Melville or the woman Virginia Woolf. We can

know little about what they as people really thought about “savages” sailing on

whaling boats or how lonely professor’s wives felt.

Precisely then, the posited author is the controlling intelligence of the story,

the emotional-thinking being who created the story in her imagination through an emotional

discovery and decided this result was what best expressed meaning for her. Shakespeare could have had a bit of Edmund in

him, or saw himself as King Lear in his own life, but he is not saying, “I am an

existentialist”, or, “Kings should rule until their death”, as his overall

message to the reader. These ideas may be

imagined by the reader because Shakespeare’s characters felt them from their position

in their “worlds”. But Shakespeare

as posited author had a much more complex intention in mind for us as readers. The effect in the last scene in King Lear

when the beaten king carries on stage the lifeless body of his daughter is impossible to

render in words. The audience is left to work

through issues of being and existence raised to new levels of consciousness.

Devereaux (7) says, “Our access to the posited author is secured through the

act of interpretation… As readers, however, the primary object of our attention is

not the pages – the ink on paper – but the story. To make sense of such judgments we must consider

the narrative from the standpoint of the reader. Seen

from that standpoint, the posited author becomes intelligible. We read under the concept of literary

purposiveness”. Therefore,

“we can dispute whether The Merchant of Venice criticizes, endorses, or merely

investigates the idea of moral payment embodied in Shylock’s “pound of

flesh”. The evidence for our judgments

about the posited author will consist in texts and the reading of texts.” In the end, moral judgments about the

literary work itself are not determining who the real life person was, but in interpreting

the emotional viewpoint of the posited author.

When students learn about their own authorial voice as posited author they see

their vision from a distance. Beyond this,

they recognize the quality of their own aesthetic experience as writers. They begin to engage with truth in emotion and

the ideas in stories and gain experience and maturity as writers and as persons. The focus moves towards elucidating their

understanding of humanity and existence. That

life is not rational becomes clear and soon they grasp that some truths just cannot be

learned through rational methods. Heidegger

states that there is a fundamental way of being that is not cognitive. In fact, it is the mirror image of

Descartes’s famous phrase, “cogito sum ergo”. It comes down to “being” instead of

“knowing”, and not the reverse. What

we see at the end of King Lear is about “being” in the world. (Pike 26). We

see the same thing in our experience of T.S. Eliot’s poem, “The Waste

Land”. There is a resistance to having

it explained by another reader because we just want to “be” in the experience. The poem eludes explication anyway, and any

attempt will fail to capture its entirety. It

is best left as art to express its own meaning. Knowledge in Art

Knowledge in art, Collingwood (289) tells us, is knowledge of the individual. Because the writer or thoughtful reader has

developed the habits of mind that allow her to think and feel for herself, she

automatically weighs the quality of her own aesthetic experience while engaging with the

art and compares the author’s ethics with her own personal ethics.

Because literature does not tell us directly what to think and feel, the reader is

imagining what the author’s words mean through a unique way of experiencing. Each reader has his own memories, way of assigning

emotion to sensum, making intellectual associations and in the end, his overall reactions

will be specific. And here is the great

paradox of literature: it is both specific and universal.

No one reader’s interpretation of a novel will be identical to another

reader’s, nor to the writer’s. One

example of this is how different the picture we have in our head of a novel is compared to

the film version we view in the theatre. We

are shocked to “see” how the director or producers have portrayed the

characters, setting, etc. It just

doesn’t match how we have envisioned it. And

yet, how could it? Imagination varies between

individuals. On another level, we are also in the habit of judging

the author’s moral sensibility. When

concepts don’t match our own, flags come up, which say, this doesn’t make sense

to my worldview; or, it is unjust or plain wrong. If

enough flags are lifted, we begin to doubt the narrator; when there seems to be no purpose

to have an unreliable narrator, we call the posited author into question. Because we are thinking and feeling for ourselves,

and therefore using our “moral imagination” as Nussbaum (162) calls it, we move

into a more critical stance.

I must clarify here the difference between a character who is immoral and the

faulty consciousness of the author. As

mentioned before, authors often use “evil” characters for a purpose; they have a

role to play in driving the plot forward. Iago,

for instance, the most cunning of villains, teaches us about the folly of pride and

gullibility by the way he manipulates Othello. Shakespeare

as posited author is not condoning people who train on other people’s weaknesses to

advance their own designs. On the other hand,

had Shakespeare made Iago a general after Othello’s death and celebrated his triumph,

we as sharp readers would shake our heads in confusion.

This ending would not fit our picture of the cosmos and our moral

imaginations cannot resolve the intentions behind such an outcome.

In summarizing our point for this section then, we might say that an interpretation

of the actual Othello will be slightly different for each person, depending on who

they are, their circumstances in life and so on, but the overall experience could be said

to be universal due to the play’s archetypes and themes. In this way, the knowledge we acquire after

spending time with literature is both specific for the individual as well as universal in

terms of humanity and existence. The

aesthetic experience, therefore, as a matter of course, delivers us into a moral universe

where ethics emerge as a natural part of engaging with the art. Ethics and Aesthetics as One in Literature

In this essay I have assumed there is an interplay between reading and writing and

have written elsewhere about why literature matters more to students who are creative

writers (Barber 2004). I would now like to

emphasize that the same interplay exists between ethics and aesthetics at the deepest

level of reading and writing.

Writers and readers have a moral responsibility to use the aesthetic experience to

verify ethics. Only a deep and prolonged

engagement with art will yield emotional truths and therefore confirm or deny the moral

health of each posited writer the reader encounters.

In Heidegger’s words, “Art is truth setting itself to work.”

Students need to be encouraged to develop the habit of engaging with literature,

not only because they need to discern what is quality art but also to exercise their moral

imaginations. For we have recognized the

dangers of a corrupt consciousness that senses the truth but turns away from it, denies it

and eventually represses it. The corrupt

consciousness prefers fantasies because it cannot dominate the impression and shrinks from

the effort. But the feeling from which

attention is distracted does not disappear; it infects the imagination to the extent that

the idea must be blamed on others, cast off or suppressed.

Collingwood (217-220) condemns the condition of a corrupt consciousness not only as

an untruth but as an example of evil. The

mind that refuses to face down this evil has delivered itself into the power of its

feelings.

What happens when a person, a society or even a whole civilization prefers

fantasies? Or, specifically, prefers the

fantasies promoted by newspapers, television newscasters or even government propaganda

departments? Taylor’s (9) third

“malaise” suggests the outcome: a

loss of freedom. When people choose the

pleasures of staying home, watching trivial entertainment and enjoying “the

satisfactions of private life, as long as the government of the day produces the means to

these satisfactions…” the future may hold a new kind of tyranny where leaders

appear “mild and paternalistic” but in fact hide a “soft” despotism

over which people will have little control. Contrasted

with recent political events in the world, Taylor’s prediction appears prescient. However, Taylor (32) is not a pessimist, and he believes the remedy for the malaises is to be found in art and what is most basic to human life: its fundamentally dialogical character. “When we come to understand what it is to define ourselves… we see that we take as background some sense of what is significant.” In the shadow of the malaises, I believe the art of teaching now demands a more active pursuit of the virtues -- more courage to resist instrumental reasoning, more honouring the slow process of emerging consciousness, more justice and perhaps more righteous indignation. For it is true that the teacher is an artist with an ethical awareness, whose business is nothing less than to teach artistic excellence as well as the meaning of life. (excerpt from Barber, Susan. “The Ethics and Aesthetics of Literature” Dec.2004) |

|

Perceiving versus Judging (Or, is this an example of a high-end Perceiver?!)As I have mentioned, MBTI uses four divisions to separate people into sixteen

different categories. One may have the impression that these four distinctions all have

equal status. The theory of MBTI, however, states that the four splits fall into two

different types. The T/F and S/N splits (the two we have already discussed) are treated as

fundamental. In contrast, the P/J and I/E divisions are viewed as modifications

that adjust the operation of the two fundamental splits.[141] A similar distinction exists in the theory of mental symmetry. We have found

that the four simple styles (Teacher, Mercy, Perceiver and Server) work with mental

content, whereas the three composite styles (Exhorter, Contributor, Facilitator) use this

content to operate the mind. Thus, when comparing MBTI with mental symmetry we should find

that the T/F and S/N splits relate to the simple styles and should discover that the P/J

and I/E splits involve the composite styles. The connection between T/F and S/N and the simple styles has already been discussed.

Now we need to examine the other two MBTI categories in the light of the composite styles.

The problem is that we will only be discussing the Exhorter, Contributor and Facilitator

in detail in a later book. So, before we look at the last two MBTI categories, I will need

to present a ‘sneak preview’ of the composite styles. Obviously, this overview

will have to be somewhat sketchy.[142] The composite styles form three stages of a mental ‘pump.’

Exhorter thought is stage one, tying together Teacher theories with Mercy experiences. The

Exhorter person ‘learns from life’ as Mercy situations get linked to Teacher

theories, and he demands that Teacher theories be applied to real Mercy experiences,

‘where the rubber meets the road.’ Exhorter strategy works with excitement, a derived sensation built upon Mercy and

Teacher feelings. Exhorter thought hates to be frustrated and avoids boredom at all costs.

It excels at starting; it is not good at finishing or following through. Finally, Exhorter

strategy is imagination. The Exhorter person can daydream for hours and he thrives

on vision and possibility. Contributor thought forms the second stage of this pump. It

makes decisions based upon Perceiver facts and Server sequences. As far as the Contributor

person is concerned, actions are always considered in the light of Perceiver facts, and

facts are not true unless they are or can be applied. Unlike Exhorter strategy, which

looks for loose relationships between grand Teacher theories and significant Mercy

experiences, Contributor strategy builds specific connections between individual

Perceiver facts and Server sequences. Contributor strategy works with confidence. It builds upon Perceiver and

Server information, which is also based in confidence. But, confidence can be overwhelmed

by excessive emotion. The Contributor person is therefore triply vulnerable to losing

control, for not only does Contributor mode use confidence, but its supporting strategies

of Perceiver and Server thought use confidence as well.[143]

Facilitator mode forms the third and final stage. It fine-tunes the

decisions made by Contributor thought. It adds shades of gray to the black-and-white of

Contributor confidence. It takes the ‘plan A’ of Contributor choice and

supplements it with elements of ‘plan B’ and ‘plan C.’

By the way, I suggest that this fine-tuning function of Facilitator strategy

explains the origins of MBTI. Our research has discovered that most psychologists and

philosophers have the cognitive style of Facilitator.[144]

I have just stated that Facilitator strategy blends and averages between the decisions

made by Contributor thought. But, MBTI describes mental splits, in which people choose to

follow one mental path rather than another. And operational choices, by definition,

involve Contributor thought. Thus it is natural that Facilitators would turn to a system

such as MBTI in order to help them to bridge the mental gaps produced by Contributor

choices. Before we return to the MBTI categories, we need one more essential piece of

information. I have mentioned that Exhorter thought combines Teacher and Mercy memories.

Exhorter strategy operates by holding a memory fixed in one of these two modes of thought

and using this as a mental anchor for moving through the other. Thus, Exhorter thought,

and the Exhorter person, can operate in one of two different modes: In

‘practical’ mode, Exhorter strategy anchors itself in a Teacher theory and finds

excitement by moving through Mercy experiences. In contrast, ‘intellectual’ mode

roots itself in a Mercy memory and then moves through the world of Teacher theories.[145] Contributor thought is the second stage of the mental ‘pump’ and

is driven by the excitement of Exhorter strategy. Since Exhorter thought has two possible

modes, Contributor strategy, and the Contributor person, also tend to fall into either a

‘practical’ or an ‘intellectual’ rut.[146] Now that we have done our homework, let us analyze the last two MBTI

categories, starting with a few quotes about Judging versus Perceiving. Myers-Briggs begins, “The judging types believe that life should be

willed and decided, while the perceptive types regard life as something to be experienced

and understood. Thus, judging types like to settle things, or at least to have things

settled, whereas perceptive types prefer to keep their plans and opinions as open as

possible so that no valuable experience or enlightenment will be missed. The contrast in

their lives is quite evident. Judgment is eternally coming to conclusions—with the

finality the word implies.” What we have here is a separation between Exhorter and Contributor thought.

Contributor mode is the ‘judger’ that wills, decides and comes to conclusions.

In contrast, Exhorter strategy is constantly searching for new Mercy experiences and

Teacher enlightenment. Does this mean that all Exhorter persons are Perceiving and all Contributor individuals

are Judging? To a first approximation, yes. However, it is possible for a Contributor

person to let go of control and allow his mind to be driven by subconscious Exhorter

urges. His MBTI type would then change from Judging to Perceiving. It is also possible,

though rare, for an Exhorter person to become Judging. It is usually the Facilitator person—stage three of the

‘pump’—who vacillates between Judging and Perceiving. Depending upon his

environment and upbringing, his behavior can vary all the way from the Perceiving of the

freethinking artist to the Judging of the hidebound bureaucrat. I should point out again that the word Perceiving now has two opposite meanings. First,

there is the cognitive style of Perceiver, a mode of thought that uses associative

processing on abstract data. Second, there is the MBTI category of Perceiving, a mental

bias that avoids solid conclusions. Very seldom does the Perceiver person have the MBTI

label of Perceiving, because facts lead naturally to conclusions and Judging. Now that we have linked Exhorter mode to Perceiving and Contributor thought to Judging,

let us look at a few more quotes: “It is natural for a judging type to decide what is the best way of

doing a thing and then consistently do it that way.” Contributor strategy makes the

decisions. It also reassembles plans in order to make them better, or more efficient. As

we will see in another volume, Contributor mode is responsible for optimization. In contrast, speaking of Perceiving: “Spontaneity is the

ability to take whole-heartedly the experience or enlightenment of the present moment,

even though some intended thing goes undone.” This describes the behavior of raw

Exhorter thought. It is driven by its current enthusiasm. It drops what it is currently

doing if something more exciting comes along. Exhorter strategy is highly motivated by excitement and repelled by boredom.

The new is exciting; the old becomes mundane and is quickly abandoned. The Exhorter person

is also the ‘instant expert.’ Briggs-Myers describes these traits: “One of

the liveliest gifts of the perceptive types is the expectation that what they do not yet

know will be interesting. Curiosity leads them into many byways of knowledge and

experience and into amassing astonishing stores of information. It also wards off boredom,

as it finds something of interest in almost any situation.” Perceptive types

“take great pleasure in starting something new, until the newness wears off.” In contrast, Contributor strategy requires stability. It wants solid,

lasting connections between facts and actions. Thus, projects are completed and not left

hanging; loose ends are tied up. As Briggs-Myers says, “Having once decided to do a

thing, the judging types continue to do it. This application of willpower results in

impressive accomplishments. The tortoise in the race was certainly a judging type. The

hare, because he liked to operate in tremendous spurts, was probably an extraverted

intuitive but lacked adequate judgment.” Judging types “take real pleasure in

getting something finished, out of the way, and off their minds.” By now, I think we have established the connection between Exhorter strategy

and MBTI Perceiving and between Contributor thought and MBTI Judging with sufficient

certainty. That brings us to the next question. I have mentioned that Exhorter and

Contributor thought can operate in either ‘practical’ or

‘intellectual’ mode. Is the Perceiving/Judging split associated with one

of these two modes? Myers-Briggs answers this question herself: “It is important,

especially for introverts, to remember that the JP preference applies to a person’s

customary attitude toward the outer world. What shows in most casual contacts with other

people (and governs the JP index on the Type Indicator) is the extraverted process, the

one usually relied on for the conduct of outer life.” And what is the ‘outer

world’? It is a realm of Perceiver objects, and Mercy experiences and feelings. In

other words, the P/J split involves the practical side of Exhorter and Contributor

thought. As further confirmation, Briggs-Myers defines the P/J split in terms of

practical experiences, not intellectual theories. For instance, judging types

“depend on reasoned judgments...to protect them from unnecessary undesirable

experiences.” In contrast, perceptive types desire “a constant flow of new

experience—much more than they can digest or use.”[147]

The distinction between ‘practical’ and ‘intellectual’ thought

could be stated in another way. Practical thought involves the real world of experiences

and facts—the realm of Mercy and Perceiver thought. Because these two operate in the right

hemisphere, we could refer to T/F and P/J as right hemisphere divisions. What

is the difference between these two? T/F is a cortical split, describing two

different ways of organizing mental content. In contrast, P/J is a subcortical separation,

describing two distinct ways of operating. While there is a correspondence between the MBTI divisions and brain

regions, it is probably best not to emphasize this relationship too strongly. That is

because these two are fundamentally opposed to one another. MBTI describes mental walls

whereas the brain is a device that operates. Using walls to describe operation

is like equating a dam to a river. A dam stops water whereas a river, by

definition, involves the flow of water. [141] MBTI is based upon mental splits. Yet, it uses these divisions to build a theory of mental operation. This inherent contradiction between separation and integration means that neither side of MBTI can be fully developed without running into problems. If one understands the mind more thoroughly, though, it is possible to put both of these aspects upon a solid footing.[142] I should mention that we developed our theory independently of MBTI. We did not ‘steal’ from them or adjust our theory to fit their information. Rather, it was only after we fully developed our theory that we studied MBTI and discovered that we had sufficient tools to analyze it effectively. As we shall see later, whenever one theory can ‘swallow up’ another without modifying either of them, this is a sign that soft science is turning into hard science.[143] Mentally speaking, he is only consciously aware of Contributor confidence. In contrast, he assumes the presence of Perceiver and Contributor confidence. If it ever ‘cracks,’ then, like a person skating on thin ice, he ‘falls through’ into the ‘cold water’ of raw experience.[144] The few who are not Facilitators by style still make heavy use of subconscious Facilitator thought and probably spend most of their time interacting with Facilitator persons.[145] This little fact is extremely significant and has major implications upon mental processing. We will use it extensively in the next book when we talk about ‘flipping modes.’[146] Another major point over which we are just skimming.[147] Could the P/J split involve abstract thought? Yes, under certain conditions. We will examine this issue in a few more pages.(from: <http: Google

Image Result for http://209.87.142.42/y/book2/Book_056.png> |