Lemur coronatus Gray, 1842

Order PRIMATES

Family LEMURIDAE

The Crowned Lemur is found in the dry forests in the north and far northeast of Madagascar. It is the only lemur to occur in the dry forests of the Cap d'Ambre. Population numbers are unknown, but it can occur at densities of more than 200 individuals per sq. km. Its range is comparatively small and is shrinking due to logging, burning and cattle grazing within the forests. This species is also hunted. L. coronatus has been studied for several months, but much remains to be learned of its ecology and social organization. It is mostly diurnal, though nocturnal activity is not uncommon. It has been seen in groups of up to 10 individuals with several adults of both sexes in the groups. It eats fruit and some leaves. There are about 45 individuals in captivity, many of which were bred there. Crowned Lemurs are found in the four protected areas in the north of Madagascar. Listed in Appendix 1 of CITES, Class A of the African Convention and protected by Malagasy law.

Found in the north of Madagascar in the dry forests of Cap d'Ambre, south of this its range extends to the west as far as the Ankarana Massif, between Ambilobé and Anivorano Nord, and to the east to the Fanambana River just south of Vohimarina (Tattersall, 1982). Its range includes the slopes of Mt d'Ambre.

Population numbers are unknown but they are considered to be probably declining (Richard and Sussman, 1987). There are a number of estimates of population density. In Analamera Special Reserve estimates of 77 ± 58 individuals per sq. km (mean and 95% confidence level) have been made, while there are reported to be as many as 221 ± 79 individuals per sq. km in the canopy forest of the Canyon Grand in Ankarana Special Reserve (Hawkins et al, in press). Even higher densities, up to 5 adults per ha (500 per sq. km) in the richest canopy forest of the Canyon Grand, have been reported (Wilson et al, 1989; Fowler et al, 1989), but the authors considered that these high densities were restricted to an area of 200 ha of selectively logged forest. Overall density throughout the Canyon Grand and Canyon Forestier was just over one individual per ha, though the density of Crowned Lemurs throughout the rest of their range was estimated to be considerably lower (Wilson et al, 1989). In the dry forest of Sakalava, population density of L. coronatus was estimated at 104 individuals per sq. km, while in the humid forest of Mt d'Ambre a density of only 49 animals per sq. km was estimated (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983).

In 1935, Crowned Lemurs were reported to be very common in the dry wooded areas of the northern savanna and to occur also in the dry forest on the slopes of Mt d'Ambre, up to about 800m, but to be absent from the higher, humid forests on the summit (Rand, 1935). However, the species is now reported to occur in these humid forests and it is suggested that this is a recent extension of their range, possibly due to pressure on their preferred habitat (Petter et al, 1977). The species does appear to be tolerant of selective tree extraction and it is found where there is constant human disturbance (Wilson et al, 1988). L. coronatus has been studied in the dry forests of Sakalava and Ankarana and in the humid forest on Mt d'Ambre (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983; Wilson et al, 1989, Fowler et al, 1989). In Ankarana, Crowned Lemurs were seen most frequently in the canopy forest, rather than in edge or degraded forest, though there was evidence that even the driest areas were used at times (Wilson et al, 1989). L. coronatus was observed at all levels in the forest though appeared reluctant to travel on the ground, mostly descending only to eat fallen fruit or lick earth (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983; Wilson et al, 1989). In contrast Petter et al (1977) found that Crowned Lemurs travelled substantial distances on the ground.

In Ankarana, the diet of the Crowned Lemur, at the end of the six month dry season, was almost exclusively made up of fruit, with leaves being taken only rarely (Wilson et al 1989). The fruits that they commonly ate there included Ficus spp, Strychinos spp Pandanus spp, Diospyros sp and Tamarindus indica (Wilson et al, 1989). It was, however, considered probable that they ate more leaves in the wet season (Wilson et al, 1989). The lemurs visited waterholes to drink during the dry season, some of these were deep inside caves (Wilson et al, 1987; 1989). In Sakalava and the humid forest on Mt d'Ambre, both fruit and leaves were eaten, though fruit seemed to be the more important component of the diet (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983).

In Ankarana, Crowned Lemurs were generally active from first light at 04.30h until after dark at 18.15h, with a rest period from approximately 10.30h to 14.30h (Wilson et al, 1989). However, some groups traveled for up to two hours after nightfall and feeding and traveling was commonly noted between midnight and 02.00h. In Sakalava, activity patterns were generally similar, though in the wet season the animals tended to be more active and the midday rest period was not so pronounced (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983). In the humid forest, activity increased, there was a short rest period early in the morning and some reduction in activity between 10.30 and 13.00 hrs (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983). Locomotion was mostly quadrupedal but some elements of "clinging and leaping" were also observed (Wilson et al, 1989).

The maximum group size seen in Ankarana was nine individuals plus two infants; groups of two and three were common and solitary animals were also seen (Wilson et al, 1989). A typical group, however, comprised five individuals, two adult pairs and a sub-adult or juvenile (Wilson et al, 1989). Arbelot-Tracqui (1983) suggests that group size is reduced in the humid forests, she recorded three groups of between eight and ten individuals (mean of nine) in Sakalava and four groups of between four and six individuals (mean of five) in Mt d'Ambre. There was little spatial cohesion between the members of a group, after resting periods some individuals would frequently remain behind for an hour or more before following the departed lemurs (Wilson et al, 1989). Interactions between groups were rare though smaller troops tended to leave feeding patches when approached by bigger groups (Wilson et al, 1989). Several aggressive interactions were observed between groups of Crowned Lemurs and Sanford's Lemurs (Lemur fulvus sanfordi), the latter usually displaced the Crowned Lemurs at localized resources, but male L. coronatus chased off Sanford's lemurs if they were approaching females with infants (Wilson et al, 1989). Petter et al (1977) report L. coronatus groups of between five and 10 individuals

In Ankarana, Crowned Lemurs gave birth from mid-September, thereby coinciding with the first rains, with the earliest births occurring in the richest canopy forest of the Canyon Grand (Wilson et al, 1989). Births were seen over the next five weeks, with the later ones being in the drier forests where fewer fruits were available (Wilson et al, 1989). Further north, in the dry forests of Sakalava and in the humid forest of Mt d'Ambre, most births occurred in the third and fourth weeks of October, (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983). However, in Sakalava, two approximately three week old infants were seen in early February and two other infants seen in August, were judged to be about three months old. These observations suggest further births in mid-January and mid-May respectively (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983). The infants were initially carried on their mothers' front but then moved to ride on her back (J. Wilson, pers. comm.). One year old males were about half adult size (Wilson et al, 1989). In captivity, gestation length has been calculated as 125 days; age at first conception has been recorded as 20 months; a male also reached sexual maturity at this age (Kappeler, 1987). Twin and singleton births appear to be equally common (Kappeler, 1987).

Poaching of lemurs in Montagne d'Ambre National Park is reported to be widespread and increasing, both L. coronatus and L. fulvus sanfordi are shot there (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989). Bush fires threaten the edges of the Park and there is illegal forestry within it (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989). Analamera Reserve is unguarded and unmanaged, it is being destroyed by logging, burning and grazing and lemurs are hunted in this area (Hawkins et al, in press). Until recently, Ankarana Reserve had remained relatively undisturbed, the lemurs are not hunted there (Wilson et al, 1989) though boys with sling shots are reported to kill some of the animals (E. Simons, in litt.). A possible disaster for the lemurs in this area has now occurred. During three weeks of May 1988, one third of the forest within the Canyon Grand was clear felled by Kharma Sawmill Company (P. Vaucoulon, pers. comm. to Wilson, 1988). It is not known whether complete clearance of the Canyon Grand is planned (Wilson, 1988).

The area of suitable habitat remaining for the Crowned Lemurs is probably less than 1300 sq. km and this is continuing to shrink (Wilson et al, 1989). Interchange between populations of L. coronatus is becoming increasingly difficult as the forest patches become smaller and more isolated (Hawkins et al, in press, Wilson et al, 1989). For instance, it is estimated that the distance between the forests of Ankarana and those of Montagne d'Ambre has increased from 10 km in 1982 to 30 km in 1988 (Wilson et al, 1989).

The Crowned Lemur occurs in Forêt d'Ambre, Analamera and Ankarana Special Reserves and in the Montagne d'Ambre National Park (Hawkins et al, in press; Wilson et al, 1988,1989; Nicoll and Langrand, 1989).

A management plan has been proposed for all four reserves in which the Crowned Lemur is found. This is being carried out jointly by the Department of Water and Forests, WWF, the Catholic Relief Service and US-AID (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989). The following (from Nicoll and Langrand, 1989) will be included in the plan:

Extra full-time guards, with better equipment, are necessary if the areas are to be adequately patrolled. It is suggested, for instance, that camping equipment and a motorbike are essential for a guard employed in Ankarana.

A conservation education programme for the villagers around the reserves which made them aware of the importance of the forests and the protected areas would be very productive. The reserves themselves have great educational and tourist potential and this could be developed. A visitor information center could be set up and marked paths cut through the reserves leading to places of particular interest. If a development plan for the local people is integrated with the management plan there is more chance that the reserves will be protected from encroachment

Domestic animals should not be allowed into the reserve. In addition, no permits to make charcoal or exploit the trees within the reserves, should be issued and the illegal activities within the reserves has to be stopped. An alternative means of providing wood should be found. Reforestation is necessary in the places where there is severe erosion. Fire breaks are needed around the protected areas.

A French teacher, B. LeNormand has released a number of Crowned Lemurs on the small, uninhabited island of Nosy Hara (Wilson et al, 1988; J. Wilson, in litt.)

Surveys are needed to determine the remaining areas of suitable habitat for the Crowned Lemurs and their population numbers so that adequate protective measures can be taken.

All species of Lemuridae are listed in Appendix 1 of the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Trade in them, or their products, is subject to strict regulation and may not be carried out for primarily commercial purposes.

All Lemuroidea are listed in Class A of the African Convention, 1969. They may not, therefore, be hunted, killed, captured or collected without the authorization of the highest competent authority, and then only if required in the national interest or for scientific purposes.

Malagasy law protects all lemurs from unauthorized capture and from hunting, but this is impossible to enforce.

ISIS (June 1989) reports that there are 36 Crowned Lemurs in captivity (Lemur mongoz coronatus in their sheets), 83% of them being captive born, most of these are descendants of three individuals caught for Cologne Zoo around 1969 (E. Simons, in litt.). According to the ISIS lists, Cologne (Koln) Zoo holds 15 individuals, Duke Primate Center has 18, there is one pair at Los Angeles and a single animal at Touroparc. It is possible that this latter animal is L. mongoz and not L. coronatus (Lernould, in litt.) In addition, there is one animal in Paris Zoo (J.-J. Petter, in litt.), and three pairs in Mulhouse Zoo and Strasbourg Université Louis Pasteur Médecine which were imported between 1981 and 1986 and are managed as a group (J.-M. Lernould, in litt.). In Madagascar, there are two pairs in Tsimbazaza, which have bred successfully (M. Pidgeon, G. Rakotoarisoa, in litt.) and three animals at Ivoloina (A. Katz, in litt.). L. coronatus is also commonly kept as a pet in Madagascar (O. Langrand, in litt.)

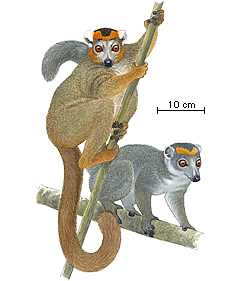

This species was considered to be a subspecies of L. mongoz until recently, but is now regarded as a distinct species. Crowned Lemurs weigh about 2kg; they are sexually dichromatic, the brown male has a triangular crown of black fur between his ears, while the female is gray with a light brown crown (Wilson et al, 1989). Females that are almost completely white have been reported on the slopes of Mt d'Ambre, though generally the individuals in the humid forest were darker than those in the dry forests (Arbelot-Tracqui, 1983). For a more detailed description of the species, see Tattersall (1982) or Jenkins (1987). The Malagasy names of the species are ankomba, varika and gidro (Tattersall, 1982; Petter et al, 1977; Paulian, 1981)