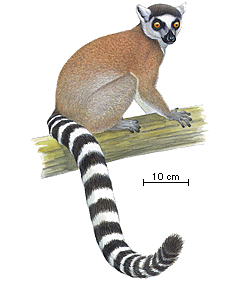

Lemur catta Linnaeus, 1758

Order PRIMATES

Family LEMURIDAE

The Ring-tailed Lemur is found in the dry forests and bush of south and south-western Madagascar. Population numbers are not known and estimates of density vary from 17 to 350 individuals per sq. km. Though previously considered not threatened, recent reports suggest this may no longer be the case. Lemur catta is one of the most studied of the lemurs. It is a medium-sized diurnal species which spends more time on the ground than any of the other lemurs. It is found in groups, containing several adults of both sexes, of up to 24 individuals. It's diet is principally fruit, leaves and flowers. It is the most common lemur in zoos, over 950 individuals are reported to be held in captivity. It is found in six protected areas. Listed in Appendix 1 of CITES, Class A of the African Convention and is protected by Malagasy law.

Found patchily distributed in the dry forests and bush of south and south-western Madagascar. The northern limit to the range of L. catta is the forest of Mahababoky (at 20°44'S, 44°0'E), in Kirindy reserve about 45 km south of Morondava River (Sussman, 1977a). The eastern limit of its range is around 46°48'E, or, approximately, along a line joining Fianarantsoa and Taolanaro (Fort Dauphin) (Sussman 1977a; Tattersall, 1982). The Ring-tailed Lemur ranges into the interior highlands further than does any other lemur (Tattersall, 1982).

No figures are available for total population number. There have been a variety of density estimates for this species, mostly at Berenty (near Taolanaro). Counts of 153 and 152 individuals in 94 hectares (167 individuals per sq. km) of the reserve were made in 1972/73 by Budnitz and Dainis (1975); an earlier estimate by Jolly (1966), extrapolating from her 10 ha study site, gave figures of 350 individuals per sq. km; while Sussman (1974), on the basis of group size and home range, calculated 250 individuals per sq. km at Berenty; estimates for 1983-1985 were 115.3 individuals per sq. km when infants were excluded and 143.7 when they were not (O'Connor, 1987). In the south-west at Antserananomby, Sussman (1974) estimated that there were 215 individuals per sq. km. In the disturbed forest of Bealoka on the Mandrare River, near Berenty, density of L. catta was estimated at only 17.4 individuals per sq. km (O'Connor, 1987). Population numbers are probably declining (Richard and Sussman, 1987).

A diurnal species that lives in brush and scrub forests and in closed canopy deciduous forests, it is also found in the dry, rocky and mountainous areas in the southern portion of the central plateau where patches of deciduous forest remain (Sussman, 1977a, 1977b). The ranging and foraging patterns of L. catta may be related to its ability to cope with these semi-arid environments in which resources are sparse and unevenly distributed (Sussman, 1977b). They probably cannot, however, survive year round in sub-desert vegetation where there is no forest (Budnitz, 1978; M. Pidgeon, in litt.). There have been several sightings of the species in very dry areas away from any forest and it is possible that they migrate into these areas during the rainy season or, alternatively, there may be water available there for some months of the year; L. catta apparently does need to drink at least ocassionally (M. Pidgeon, in litt.).

Most of the studies of this species have been in Berenty, a Private Reserve near Taolanaro (Fort Dauphin), which is owned by the de Heaulme family (Jolly, 1966, 1972; Klopfer and Jolly, 1970; Budnitz and Dainis, 1975; Sussman, 1974, 1977c; Mertl-Millhollen et al, 1979; Jolly et al, 1982; Jones, 1983, Howarth et al, 1986, O'Connor, 1987, Mertl-Millhollen 1988). Sussman (1974, 1977b) has also done a short study at Antserananomby, just north of the Mangoky River in the west of Madagascar. A long term study of the social organisation, demography and reproductive behaviour is underway in Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve in the south-west (Sussman, 1989; Sauther, 1989).

The Ring-tailed Lemur has been seen feeding on fruit, leaves, flowers, bark and sap from at least 34 different species of plant, but particularly from Tamarindus indica, the kily tree (Jolly, 1966; Sussman, 1974, 1977b and c; O'Connor, 1987). At Bealoka, the lemurs raided crops and ate melons and the leaves of sweet potatoes (O'Connor, 1987). In addition, L. catta has been seen eating small quantities of dead wood, earth and invertebrates (O'Connor, 1987). The amount of time the lemurs spent eating each type of food varied between study sites, seasons and years. For instance, Jolly (1966) observed the Ringtailed Lemur spending 70% of its feeding time eating fruit and 25% eating leaves (studied between February-September, 1963 and March-May 1st 1964), while at the same site in November 1970, Sussman (1974, 1977c) recorded L. catta eating 59% fruit, 24% leaves, 6% flowers and some herbs, bark and sap; only 23% of their feeding time was spent eating Tamarindus indica (mostly leaves and pods), half that recorded by Jolly. Between July and September 1970 at Antserananomby, fruit was eaten for 33.6% of the observations, leaves for 43.6%, herbs for 14.6%, and flowers for 8% (Sussman, 1974, 1977c). There were two peaks of feeding during the day, with a rest period of two hours or so around midday (Sussman, 1977c).

Ring-tailed Lemurs are active and feed in all the strata of the forest and they, more than any other lemur, spend considerable periods of time on the ground (Budnitz, 1978; Sussman, 1974, 1977b). Sussman (1977b) found that they spent over 30% of their time on the ground at both his study sites, 70% of travel was on the ground. O'Connor (1987), however, reports only 15.8% and 17.8% of time spent on the ground in Berenty and Bealoka respectively; most travel occurred there. The Ring-tailed Lemurs were outside the area of continuous canopy for over 58% of the day, although they slept in the canopy at night (Sussman, 1977c).

The size of L. catta groups ranges from three to 24 individuals (Budnitz and Dainis, 1975 Jolly, 1966; Sussman, 1974, 1977b, 1989; O'Connor, 1987), with sex ratios varying between 0.6 to 2.7 adult males to females (Jolly, 1966). Within the groups there is a well defined dominance hierarchy, with the females being dominant over the males (Sussman, 1977b, Jolly, 1966). This tends to give rise to subgroups and during movement the troop can be spread out over 20 to 30 m with the subordinate males lagging in the rear (Jolly, 1966; Sussman, 1977b).

The home range size of L. catta appears to be directly related to the abundance and distribution of resources, including water (Sussman, 1977c). For instance, Budnitz and Dainis (1975) found that a troop of Ring-tailed Lemurs living in open forest, brush and scrub had a home range of 23.1 ha. as compared to their figures of 6.0 and 8.1 ha for troops living in "richer" closed canopy forest. In the disturbed forest of Bealoka, a group of nine animals used a range of at least 34.6 ha (O'Connor, 1987). The troops studied by Jolly (1966) and Sussman (1974) had ranges of between 5.7 and 8.8 ha. Day ranges averaged 950m (Sussman, 1977b). The degree of overlap between home ranges also changed between study periods. Each group maintained almost exclusive use of its home range and boundaries overlapped only slightly at Antseranoanomby and at Berenty in 1963-64 (Jolly, 1966; Sussman, 1977b). However, at Berenty in 1970, groups shared a large portion of their home range, though they used the overlap areas at diferent times, and intergroup encounters were more frequent (Jolly 1972, Sussman, 1974, 1977b). This same situation was recorded by O'Connor (1987) during her study in Berenty from April 1984 to September 1985.

L. catta begins mating in mid-April (Jolly, 1966; Budnitz and Dainis, 1975). Results from studies of L. catta in captivity have indicated that gestation period in this species is between 134 and 138 days (Van Horn and Eaton, 1979). In the wild, infants are born from midAugust to November, but mostly in August and September (Jolly, 1966; Budnitz and Dainis, 1975, Sussman, 1977b). Twins are produced in captivity and in the wild, but singletons are more common (Van Horn and Eaton, 1979; O'Connor, in litt.). The infant initially clings to its mother's front, within three days of birth it is moving around actively on its mother (Jolly, 1966, Sussman, 1977b, Klopfer and Boskoff, 1979), and by about two weeks of age it is regularly riding on her back (Sussman, 1977b). At two and a half months, although it is still carried by its mother when the troop moves, it plays with other offspring, explores its environment and climbs about in the trees and bushes tasting various foods (Sussman, 1977b). It takes two years for a female to mature, but then it seems that the majority can give birth every year (Jolly, 1972). At Beza Mahafaly it is reported that females first gave birth at three years old (Sussman, 1989). In 1987, 86% of the females there gave birth; infant mortality was 20% in the first six months of life (Sussman, 1989). Females remain in their natal area, while males transfer between troops (Jolly, 1966; Jones, 1983; Sussman, 1989).

Recent satellite surveys of the gallery forest remaining in the south of Madagascar suggest that it has diminished alarmingly (Green and Sussman, in prep). The two basic habitats of L. catta, the dense euphorbia bush and the riparian forest, are fairly restricted and are diminishing due to fires (set to promote grass growth), overgrazing by livestock and tree felling for making charcoal. As a result, this species may be more threatened than has been thought in the past (Sussman and Richard, 1986; A. Jolly, in litt.). It is hunted with dogs in some areas and it may be vulnerable to hunting pressures (Sussman and Richard, 1986). Severe hunting has almost certainly lowered the population of L. catta in Bealoka Forest to a critical level (O'Connor, 1987). Individuals are frequently kept as pets in Madagascar (O. Langrand, in litt.).

This species is found in all the protected areas within its range, namely: Isalo National Park, Tsimanampetsotsa, Andohahela and Andringitra Nature Reserves, Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve and Berenty Private Reserve (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989). Of these, Isalo and Tsimanampetsotsa are the only Government-run Reserves which do not have management and development plans either already underway or in the process of being formed (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989).

This is one of the few species that has been studied for more than a few months. In 1987, a long term study, involving individual marking of all the L. catta in the site, was begun in Beza-Mahafaly (Sussman, 1989).

Surveys are needed to determine the distribution and population numbers of the remaining Ring-tailed Lemurs and whether gallery forests and/or water are essential for its survival (Sussman and Richard, 1986; M. Pidgeon, in litt.).

All species of Lemuridae are listed in Appendix 1 of the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Trade in them, or their products, is subject to strict regulation and may not be carried out for primarily commercial purposes.

All Lemuroidea are listed in Class A of the African Convention, 1969. They may not, therefore, be hunted, killed, captured or collected without the authorization of the highest competent authority, and then only if required in the national interest or for scientific purposes.

The laws of Madagascar protect all lemurs from unauthorised capture and from hunting. These are, however, difficult to enforce.

The Ring-tailed Lemur breeds very well in captivity. Females frequently bear and raise twins and there have been three cases of triplets being successfully raised at Duke Primate Center (E. Simons, in litt.). It is the most common lemur in captivity. ISIS (June, 1989) lists 784 individuals (95% captive born) in 93 institutes. Wilde et al (1988) list a further 212 individuals in European institutes that are not included in the ISIS lists. In Madagascar, there are four individuals at Ivoloina and 13 in Parc Tsimbazaza (A. Katz, M. Pidgeon, G. Rakotoarisoa, in litt.).

L. catta is probably the most familar of the lemurs because of its comparatively frequent occurrence in zoos. It is a medium-sized species, weighing around 2.3-3.5 kg. There are no pelage differences between the sexes. Fur on the back is usually brown-grey, rump and limbs are light grey. Underparts are white or cream. Forehead cheeks, ears, and throat are white. There are black rings round the eyes and the muzzle is black; the tail is banded black and white. For a more detailed description see Tattersall (1982) and Petter et al, (1977). Malagasy names are maki and hire (Tattersall, 1982).