Published in Organised Sound, 8(1), 2003, pp. 117-124

The absence of gay themes and homoeroticism in electroacoustic music is discussed within the context of issues of gender and music that have been raised in the last decade. The author's emerging body of work that deals with these issues suggests possible uses of voice, text, video and music theatre within an electroacoustic language to portray sexuality and desire.

1. BACKGROUND

In proposing a discussion of the topic of homoeroticism and electroacoustic music, I am reminded of the 'politely sceptical' response that Roger Lonsdale received when he announced his interest in 18th century women poets, 'Were there any?'. Fortunately his research resulted in an Oxford anthology (Lonsdale, 1990) with 500 pages of examples of their work, along with his commentary that the 18th century saw a remarkable increase from just a few published women poets at its start to many more at its close. However, at the start of the 21st century, I would be hard pressed to find many examples of homoeroticism in electroacoustic music other than my own work and various performance pieces where live electronics is a component (see the Discography). It will be interesting to see if the situation has changed by the close of the century.

The question of this absence merits some speculation. Eroticism and gender issues in general seem curiously absent from electroacoustic music in its practice, and only as recently as 1995 were these issues raised by Hannah Bosma, Mary Simoni and Andra McCartney within the electroacoustic community, namely at the International Computer Music Conference in Banff, Alberta, where coincidentally I presented an act from my electroacoustic opera, Powers of Two, which featured two male singers, one of whom is a gay character (Truax, 1996). Discussion that arose at that conference and subsequently in other venues has centred on the role of women in electroacoustic music (McCartney, 1993), asking for instance, whether they have been 'filtered out' by processes within a 'techno-macho' culture associated with technology in general, and electroacoustic music in particular. Considerable effort has been made, at least in certain quarters, to encourage women composers of electroacoustic music and feature their work.

Since there appears to be a lack of gay themes in electroacoustic music, the same question could be asked as to whether gays and lesbians have been 'filtered out' of the system as well, perhaps for similar reasons to do with technology. In my experience, there are indeed far fewer gay and lesbian composers of electroacoustic music than one would find in the instrumental music community, and very few of them can be said to be 'out'. If one considers the artistic milieu beyond the electroacoustic music community, their absence seems even more remarkable. The 20th century has seen not only a highly visible presence of gay artists and writers, but also the proliferation of gay themes in their work. Homoerotic poetry, novels, films, dance and theatre works are numerous, even commonplace, and much of the public focus is on the extent to which these influences are 'invading' mainstream television and cinema. Within the arts community a gay presence is a given.

Before we rush to condemn the electroacoustic music community as 'behind the times', it might be wise to survey the role of gay artists in the music field generally. Although the entire scope of this question lies beyond this paper, it can be noted that it wasn't until the 1990s that gay or 'queer' issues were raised within the practice of musicology, most notably with the landmark publication of Queering The Pitch in 1994 (Brett, Wood and Thomas, 1994) as the culmination of the work of a dedicated group of American musicologists; see also (Solie, 1993; Gill, 1995). Their work built on the pioneering efforts of so-called 'radical' musicologists such as Susan McClary, Richard Leppert, John Shepherd and others, who in the 1980s suggested that music be considered within its social, hence gendered context, as expressed in their seminal anthology Music and Society (Leppert & McClary, 1987).

The debate that followed these publications, which continues periodically to this day, has its highest profile in the issue of whether such-and-such a composer 'was' gay (assuming that our modern term can be retrofitted to describe an historical personage). Speculation on the sexual orientation of such icons of Western classical music as Schubert and Handel have provoked intense controversy, possibly to the detriment of a realization how a composer living and working within a particular homosocial environment (e.g. Handel in the Italy in the early 18th century) might have responded to that situation in their musical output. Why do these issues provoke such a debate? Why should it be such an affront if the composer of the Messiah were shown to be a homosexual, when the painter of the Sistine Chapel most certainly was?

Since the middle of the 19th century, the music of various composers has had a specific gender attached to it, often in pairs. The heterosexual stalwarts of European classical music, Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, are gendered as masculine, with Handel, Schubert and Tschaikovsky gendered as their respective feminine counterparts. This issue, as simplistic as it may seem, directs our attention towards the music and away from the biography. In the 20th century, with its emphasis on a plurality of musical styles, it seems that gender and sexual orientation have become detached from the composer's chosen stylistic allegiance. The musical establishment claims that its artistic choices are devoid of discrimination because musical quality is all that matters. Women and gay composers often are heard to echo this sentiment by denying they are any different from their male or heterosexual counterparts. They are simply composers who happen to be women or gay or whatever other category. In fact, a blind listening test with their music would probably find little difference in 'voice' between such composers. Maybe the traditional musicologists are right after all - instrumental music aspires to a level of abstraction where issues such as gender or sexual orientation play no role.

Such neutrality, however, cannot be maintained in the other bastion of Western culture, namely opera. Voice, text, and drama render every aspect of opera highly gender specific. The heterosexual norm as exemplified in romantic love remains central and inescapable until well into the 20th century, if not beyond. Alternative viewpoints, as in other areas of society, have to be indulged in as subtexts, understood by initiates while preserving the veneer of normality. The tradition of 'trouser roles' for women in opera, for instance, provides a delicious double entendre (Blackmer and Smith, 1995), as did possibly the castrati and counter-tenors of earlier times. There is a long tradition of homosexual attraction to opera where a tragic heroine can be identified with (Koestenbaum, 1993), or where the extended register of the mezzo-soprano from deep masculine notes to high feminine ones can have similar appeal, reportedly a formative influence on Walt Whitman, for instance (Schmidgall, 1997).

However ambiguously gender may have been read by homosexuals, opera, particularly in the 19th century, remained securely rooted in its heterosexual norms, with no instance of a gay positive character emerging until as late as Alban Berg's Lulu and the Countess Geschwitz, arguably the only person in the opera who really loves, and is ready to die for, the title character. It is now thought that this sympathetic portrayal is related to Berg's sister Smaragda being lesbian. In Britain where homosexual activity remained illegal through most of Benjamin Britten's career, his operas appear to transmute homosexuality into the role of a generic (but sympathetic) outsider, as in Peter Grimes, or into a tragic encounter between goodness and evil within a homosocial naval environment, as in the characters of Billy Budd and John Claggart. Not surprisingly, critics still debate whether a homoerotic reading of these works is valid.

2. THE ELECTROACOUSTIC ERA

Given this background, it may be easier to see why, at least in its first 40 years or so, there has been little concern for gender issues in electroacoustic music, and few if any alternative expressions of desire or eroticism. First of all, the Western privileging of abstraction in music provides a theoretical ground for its continuation in electronic and computer sound synthesis, and even with electroacoustic music based on real world sounds. Pierre Schaeffer quickly became troubled by the 'anecdotal' nature of his concrète materials, and sought to create an abstracted approach, now known to us as a principle of acousmatic music (Emmerson, 1986). Linda Dusman (2000) argues that it is the very absence of the body in electroacoustic music that creates an uneasiness of gender identification with its abstract sounds. An alternative model would involve contextually based music creation (Truax, 1994a, 2000), even if the result is a virtual world, or else a more dramatically enacted realization.

Secondly, electroacoustic music emerged during the post World War II era when male control of technology, from educational and consumer training through to the engineering profession in general, and audio engineering in particular, was the norm (Truax, 1992b, 2001). Only recently have women been able to make any headway into male-dominated audio professions (Sandstrom, 2000). As a result, men working together with technology create a homosocial environment, similar to that found in sports and the military, where strict taboos on homosexual activity are enforced and result in expressions of homophobic denial. A musical version of this homosocial situation occurs within the traditionally male-dominated jazz community that also has been largely homophobic. Exceptions can occur, such as the case with Billy Strayhorn, whose homosexuality was tolerated through his professional role as Duke Ellington's pianist and arranger. Although there has not, to my knowledge, been widespread homophobia in the electroacoustic music community, there has been a tacit avoidance, or at least an absence, of expressions of homoerotic sensibilities, interesting exceptions being Alessandro Cipriani's Still Blue (Homage to Derek Jarman) for mime, saxophone, cello, piano, video and tape, which also exists in a video version, and Matthew Suttor's interactive performance work Sarrasine, for performer with tape and video based on Balzac's novella and Roland Barthes' 'S/Z', the story of a French sculptor who falls in love with an Italian castrato.

When vocal performance or voice recordings have been included in electroacoustic practice - which inevitably bring gender issues into play - Bosma (1995) has noted that the predominant choice by male composers is the live female voice, often with no text or only semi-comprehensible text, and usually in the soprano range, though greater variety of gendered voice is found with the tape component. A typical performance involving the male composer and/or technician hidden behind a mixing console wielding considerable audio power, with a female performer on stage as a visual display, seems to reflect stereotypical gender roles in our society. The situation has a strong parallel to the male painter at his easel depicting the nude female model, traditionally as an object of desire, but in the 20th century often portrayed in a distorted, even neurotic fashion. Male electroacoustic music practitioners have done little so far to question these power-based gender roles.

3. AN ALTERNATIVE VOICE EMERGES

Art is said to mirror society, but if you look in the mirror and see no reflection, then the implicit message is that you don't exist. Hence, the role of electroacoustic technology should be to allow, encourage and facilitate alternative voices to emerge and be heard, freed from some of the constraints of traditional music creation. Although access to this technology will always remain an important issue, since the emergence of such voices presupposes this access, an even more important and difficult issue is the incorporation of other points of view into the work itself, what I am calling 'other voices'. In other words, the composer progresses from being an artist who happens to be a woman, gay, lesbian, transgendered, of colour, and so on, to one for whom any and all of those qualities become integral parts of their work. I believe the emergence and legitimation of these alternative voices is the only way to combat the hegemony of technology and its control over our lives.

In my own case, I can date the interest in voice and gendered text and its integration within my compositional work to the late 1980s when I began working with sampled sound and its processing, most notably with granulation techniques (Truax, 1992a, 1994b). This interest in turn grew out of a focus on timbral design during the previous 15 years. Timbre, as John Shepherd (1987) reminds us, is the central entity that links sound to the real world; it 'speaks to the nexus of experience that ultimately constitutes us all as individuals. The texture, the grain, the tactile quality of sound brings the world into us and reminds us of the social relatedness of humanity.'

My first work based on the granulation of sampled sound was The Wings of Nike (1987) whose sole source material for three movements was two phonemes, one male, the other female. They were used with high densities of grains, including transpositions up and down an octave, thereby sometimes blurring the distinction in gender. A more extensive use of gendered text was involved in Song of Songs (1992) where a decision had to be made how to use the original Song of Solomon text which includes lines that are conventionally ascribed to the characters of Solomon and Shulamith, his beloved. The simple solution was to have both the male and female readers of the text record it without changing any pronouns. When these versions are combined, the listener hears both the male and female voice extolling the lover's beauty, comparing it to the bounties of nature, as well as erotic lines such as the refrain:

I am my beloveds and my beloved is mine, he feedeth among the lilies.

There is frequent use of time stretching in the piece, from slight prolongations of spoken syllables to render it more rhythmic and song-like, through longer stretches that emphasize the inflection patterns of the reading, and finally to extreme extensions where the vocal sound becomes an ambient texture. Granular stretching of a voice, by adding a great deal of aural volume to the sound with the multiple layers of grain streams (Truax, 1998), often seems to create a sensuousness, if not an erotic quality in the vocal sound. A word becomes a prolonged gesture, often with smooth contours and enriched timbre. Its emotional impact is intensified and the listener has more time to savour its levels of meaning. Song of Songs exploits this effect throughout the work, reserving the larger degrees of stretching for interludes after each portion of the text is heard where the tape accompanies the equally sensual lines of the live oboe d'amore or English horn and the curvilinear forms of projected computer graphics by Theo Goldberg.

Throughout the work there is a blurring of boundaries, a metaphor for love itself. For instance, the highly stretched voices referred to earlier resemble ambient sounds, while the actual soundscape recordings (e.g. birds, cicadas, crickets) that are also stretched and harmonized begin to resemble human utterances. The musical references to melodies from the Christian and Jewish traditions also become increasingly intertwined as the piece progresses. Likewise, the gendered text and the male and female voices speaking it are often intermingled and their distinctions blurred. For instance, the famous 'I am the Rose of Sharon, the Lily of the Valley' text is recited by the female voice with three accompanying transpositions downwards into the male voice range. The blurring of heterosexual and homosexual portrayals of the text reaches an emotional peak in the third movement, 'Evening,' which uses the text:

He brought me to the banqueting house and his banner over me was love.I sat down under his shadow and his fruit was sweet to my taste.

Thou art all fair my love, there is no spot in thee.

The joints of thy thighs are like jewels, the work of the hands of a cunning workman.

This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes.

Until the day break and the shadows flee away, I will get me to the mountains of myrrh and the hill of frankincense.

I am my beloveds and my beloved is mine. I am my beloveds and his desire is towards me.

Accompanied by a crackling fire, the male and female voices share this text, sometimes reflecting an opposite sex form of address, and sometimes a same sex form, such as when the male and female voice share the phrase 'thy breasts are clusters of grapes' but the female voice prolongs the phrase. The most explicitly homoerotic moment occurs at the climactic point where the male voice brings out the final phrase 'his desire is towards me' (3:25), leading to the most heavily stretched and expanded version of the word 'desire', accompanied by the prolonged singing voice of a monk, the crackling fire, and a florid elaboration of the cantillation melody played by the English horn.

Song of Songs was a direct inspiration for the creation three years later of the music theatre piece Powers of Two: The Artist (1995), which would later become Act 2 of the complete opera Powers of Two which I have summarized previously (Truax, 2000). The four main characters of the opera include a heterosexual couple (soprano and baritone, as an alternative to the conventional soprano/tenor pairing), a gay lyric tenor (The Artist) and a lesbian mezzo-soprano (The Journalist). The texts for Act 2 have been presented and discussed previously (Truax, 1996). I decided to begin the composition of the opera with this act because it was the one with only male characters, and up to that point I had fallen into the pattern identified by Bosma (1995) of writing only for female voice (though I had used a spoken male voice as taped material in The Blind Man (1979), Wings of Nike, and Song of Songs, as described above). Even though the two male roles in this act (Artist and Seer) are not lovers, their vocal ranges are similar (lyric tenor and counter-tenor) yet distinguishable. The intertwining of two high-pitched male voices creates a potentially homoerotic sound that, it seems, most heterosexual composers have avoided, though an operatic example involving tenor and baritone will be discussed later.

Much of the dramatic story of the opera involves the respective quests of each character for a partner, as well as for psychological and spiritual fulfillment. Acts 2 and 3 feature the homosexual characters and explore the theme of the 'imaginary other' who appears as a desirable but unattainable video image projection. The 8-channel tape accompaniment consists mainly of vocal material provided by the counter-tenor and alto voices featured in those acts, respectively, expanded by means of resonators and granular time stretching such that the live performers (and audience) are immersed within a vocal soundscape. The quest by each character is couched in terms of artistic inspiration for the Artist and a 'media story' for the Journalist. In keeping with these contrasting situations, the 'desirable other' for the Artist appears as aestheticized and idealized male images on video, and as female models derived from television advertising for the Journalist. Each character must forsake these illusory images to progress in their quest. For the Journalist this means abandoning material pursuits, as symbolized by her becoming the successor to the Sibyl character (an alto) and being renamed Sappho. The Artist learns that the answers he seeks are not in the external world, symbolized by the Seer character to whom he turns but cannot understand, but rather within himself. His final acceptance of himself, as well as his lover, is embodied in his final text, 'I embrace you in me'. The actual 'partner' for each character turns out to be the dancers from Act 1 who mirrored them but whom the singers couldn't see. Both pairs are united in Act 4.

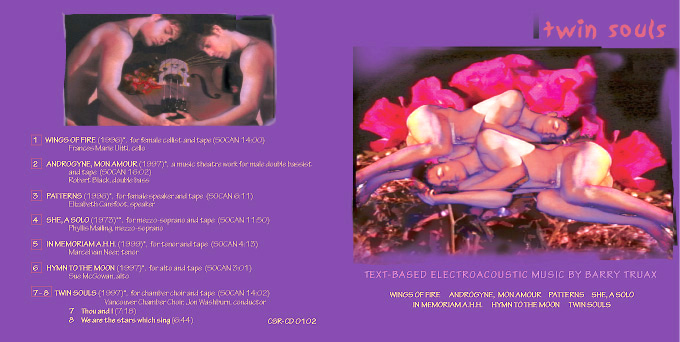

4. TWIN SOULS

My most recent CD, called Twin Souls, presents a collection of electroacoustic works with gendered texts and various styles of live performer interaction with those texts. The central theme of the 'twin soul' can be applied to a variety of forms of human desire for another being, whether a 'mirror image', an idealized partner, or a complementary 'opposite'. Disembodied electroacoustic sound, which I often design as a larger-than-life image of the live performer, seems particularly appropriate for creating this mirrored role. However, this archetype, whether interpreted as an opposite sex or same sex relationship, takes on a different interpretation in the latter instance. As pointed out by William Roscoe (1995) and others, the myth of the archetypal or divine male Twins has a long history (e.g. Baldr and Loki in the Norse Eddas, or Gilgamesh and Enkidu, the subject of my second opera, Gilgamesh), one that can inform our understanding of gay partnerships and other same sex friendships.

The twin soul theme is explored in two choral arrangements, the title tracks of the CD, based on music from Powers of Two. The first, subtitled 'Thou and I', brings together two texts, the first from Rumi (1207-1273), and the second from the Katherine Philips (1631-1664):

Happy the moment when we are seated in the Palace, thou and I,With two forms and with two figures but with one soul, thou and I.

The colours of the grove and the voice of the birds will bestow immortality

At the time when we come into the garden, thou and I

The stars of heaven will come to gaze upon us;

We shall show them the Moon itself, shall be mingled in ecstasy,

Joyful and secure from foolish babble, thou and I.

Jalal al-Din Rumi: The Divan of Shams I Tabriz (trans. by R. A. Nicholson)

Thus our twin-souls in one shall grow,

And teach the World new love,

Redeem the age and sex, and show

A flame Fate dares not move:

And courting Death to be our friend,

Our lives together too shall end.

Katherine Philips: To Mrs. M. A. at Parting

The love expressed by Rumi is for the dervish Shams al-Din, of Tabriz, whom he saw as a spiritual partner, and that of Katherine Philips is for her close women friends, a type of love that differed from what she felt for her husband. This type of same sex bonding is best expressed in the text used in the second choral arrangement (derived from the Journalist's aria in Act 3 of Powers of Two) that reads in part:

I did not live until this timeCrowned my felicity,

When I could say without a crime,

'I am not thine, but thee.'

…

Then let our flames still light and shine,

And no false fear control,

As innocent as our design,

Immortal as our soul.

Katherine Philips: To My Excellent Lucasia, On Our Friendship

Two other excerpts from Powers of Two are included on the CD, namely In Memoriam A.H.H., the male duet from Act 1, and the Sibyl's Hymn To The Moon from Act 3. The former is based on a stanza from Alfred, Lord Tennyson's monumental collection of 131 poems dedicated to the memory of his friend Arthur Hallam who died unexpectedly.

Thy voice is on the rolling air;I hear thee where the waters run;

Thou standest in the rising sun,

And in the setting thou art fair.

What art thou then? I cannot guess;

But tho' I seem in star and flower

To feel thee some diffusive power,

I do not therefore love thee less:

My love involves the love before;

My love is vaster passion now;

Tho' mixed with God and Nature thou,

I seem to love thee more and more.

Far off thou art, but ever nigh;

I have thee still, and I rejoice;

I prosper, circled with thy voice;

I shall not lose thee tho' I die.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson: In Memoriam A.H.H., CXXX

In the opera, the duet is between the heterosexual baritone and the gay tenor, but in keeping with the twin souls theme of the CD, the recorded version is multi-tracked by the tenor taking both parts and continuing into the next solo, based on a stanza from Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass (Songs of Parting). It has frequently been remarked that there are few male duets in the traditional opera repertoire, presumably because of the absence of any loving relationships between men in their plots. Males singing together in opera, other than as a chorus, are usually those in competition or conflict, if not outright battle. The exception that proves this rule is the oft quoted 'Pearl Fishers Duet' from Bizet's Les Pêcheurs de Perles, where the two male friends, Nadir and Zurga, recall when they were both in love with the same beautiful woman, but chose to renounce her in order to remain friends. Such sensible behaviour was presumably acceptable in the 19th century because the opera was set in an exotic non-European location (Ceylon), whereas the same situation in a European one would have inevitably involved a duel and death (such as that portrayed in Eugene Onegin).

In my parallel version of this situation, all of the characters in Act 1 are confused in their search for love, and in the duet the gay tenor thinks he's in love with the baritone who in turn is infatuated with the video image of the soprano. In singing the above text, the tenor and baritone take alternate phrases and join together on the last line of each stanza, thus mirroring each other and uniting, even if the object of their love is not mutual. The failed embrace that follows and destroys the tenor's illusion of love results in the Whitman song of parting from an unknown lover.

All of these works can be regarded as the reclaiming of a same-sex reading of traditional texts, particularly lyrical expressions of love. My treatment of them brings out their homoerotic implications, but the original texts keep this interpretation as a subtext. To develop these ideas further, I turned to the lyrical homoerotic poetry of Tennessee Williams found in his anthology Androgyne, Mon Amour (1977), my work taking the same title. As described earlier (Truax, 2000), the first version of the work is a music theatre piece, written for the American virtuoso double bass player, Robert Black, whose recorded performance appears on the Twin Souls CD. The poems, as read by Douglas Huffman, are heard on tape, and in the performance an illusion is created that they are addressed to the instrument itself as the 'androgyne' character of the text. To support this illusion, the text is often processed through resonators that model a physical string and are tuned to the pitches of the open strings on the bass. Thus, the male performer, whose voice is represented by the poetry on tape, becomes intertwined with the sound of the bass that is usually gendered as male (in contrast to the cello that is usually gendered as female). The expanded versions of the voice and bass on tape similarly create a sensuous soundscape that reflects this homoerotic relationship.

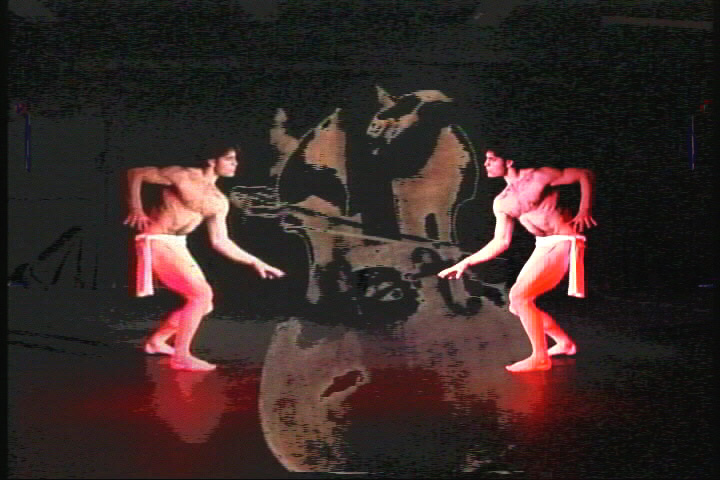

To accompany the CD, a video version of the work was prepared in which a male dancer, Walter Kubanek, acts out the role of the androgyne. At several key points in the video the image of the dancer is superimposed on that of the bass as played by Robert Black. In the opening sequence, 'You and I', the illusion is intensified by seeing the nearly nude body of the dancer, head down, feet in the position of the instrument's neck, being stroked and bowed by the bassist. The image cuts to a closeup of the dancer's body being struck by a real bow during the col legno gestures. In the subsequent solo dance sequence, the dancer appears twinned (through superimposition of a digitally reversed image) with a mirror image of himself. When the piece returns to the second half of the 'You and I' poem at the end, the mirror sequence is repeated, this time with a 7 second delay. This amount of de-synchronization creates the illusion of a second character rather than a mirror image, in keeping with the text, 'Who am I? … An enemy of yours. Your lover.'

The only other poem used in its entirety is 'Winter Smoke', which does not advance the story but captures gendered images that are related to the theme of the work.

Winter smoke is blue and bitter:women comfort you in winter.

Scent of thyme is cool and tender:

girls are music to remember.

Men are made of rock and thunder:

threat of storm to labor under.

Cypress woods are demon-dark:

boys are fox-teeth in your heart.

During the first two stanzas the dancer is seen cross-dressed as a female character. In the third and fourth stanzas, he reverts to male dress, first as an aggressive, struggling man, then as an attractive adolescent, with short cut-away's to a bare-chested version on the snap pizzicato that synchronizes with the 'fox teeth' image of the poem.

The erotic peak of the work, entitled 'Liturgy of Roses', shows the dancer first asleep and then waking superimposed over the seated bassist playing harmonic glissandi, and then in a duet with the bass instrument itself against a background of a closeup of the instrument covered in roses. The dancer moves sensually around the instrument exploring its curves and apertures, the cadence of this sequence cutting to a closeup of the dancer asleep in an embrace of the instrument. A twinned version of this image is on the back cover of the CD booklet.

The next scene, 'Wolf's Hour', depicts the aftermath of the erotic encounter, when it's 3 am and the lover has left. The bassist is smoking a cigarette, then looks longingly at the instrument lying on the ground and moves to caress it, at which point an image of the sleeping dancer is superimposed. The twinned version of this image appears on the CD cover. Williams expresses the memory of the encounter lyrically as follows:

Nevertheless there is this bit of comfort:in my hands' curved remembrance there remains indelibly

the unclothed flesh of the youth who refused to stay longer,

and I could settle for less,

God knows if not unknowing.

In the video version, two versions of the dancer are superimposed, one sleeping, the other which gets up from the prone position and begins to exit across the screen, pausing at two points while the mournful musical line ascends through the entire compass of the instrument. The video makes the homoeroticism of the text and the music much more explicit, but ultimately it is a visualization of the drama played out in the live performance version where the 'desired other' must be imagined by the listener.

5. CONCLUSION

Access to electroacoustic technology by women or minority groups will always remain an important issue. However, equally important and perhaps more challenging is what other visions the technology will allow the artist to express. If everyone gains the opportunity to sound alike, will we call it equality? Over the last dozen years or so, I have embarked on an artistic journey to create works that are contextually based, as distinct from those that remain abstract. Soundscape compositions and text-based music theatre works (Truax, 2000) have been the main vehicles for this exploration. Besides designing the works such that they are inextricably linked to and shaped by their contextual references, I find it to be a further challenge to make them more 'universal' such that they will have a life beyond their origins. Only time will tell whether the strategies I have used will assure that longevity. Gender and sexuality seem to be some of the trickiest issues to deal with artistically, particularly musically. It is not difficult to see why most composers have avoided an engagement with them. On the other hand, these aspects are at the centre of our lives and our ways of being in the world, and we ignore the energy they provide at our peril if we exclude them from our creative endeavours.

REFERENCES

Blackmer, C. and Smith, P. 1995. En Travesti: Women, Gender Subversion, Opera. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bosma, H. 1995. Male and female voices in computer music. Proc. of the Int. Computer Music Conf. (Banff, Canada), pp. 139-142. San Francisco, CA: International Computer Music Association.

Brett, P., Wood, E., and Thomas, G. 1994. Queering The Pitch: The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology. New York: Routledge.

Dusman, L. 2000. No bodies there: absence and presence in acousmatic performance. In P. Moisala and B. Diamond (eds.) Music and Gender. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Emmerson, S. 1986. The relation of language to materials. In S. Emmerson (ed.) The Language of Electroacoustic Music. London: Macmillan.

Gill, J. 1995. Queer Noises: Male and Female Homosexuality in Twentieth Century Music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Koestenbaum, W. 1993. The Queen's Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire. New York: Poseidon Press.

Leppert, R. and McClary, S. (eds.) 1987. Music and Society. Cambridge University Press.

Lonsdale, R. (ed.) 1990. Eighteenth Century Women Poets. Oxford University Press.

McCartney, A. 1993. Inventing metaphors and metaphors for invention: women composers' voices in the discourse of electroacoustic music. In B. Diamond and R. Witmer (eds.) Canadian Music: Issues of Hegemony and Identity. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Roscoe, W. 1995. Queer Spirits. Boston: Beacon Press.

Sandstrom, B. 2000. Women mix engineers and the power of sound. In P. Moisala and B. Diamond (eds.) Music and Gender. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Schmidgall, G. 1997. Walt Whitman: A Gay Life. Penguin Books.

Shepherd, J. 1987. Music and male hegemony. In R. Leppert & S. McClary (eds.) Music and Society, pp. 151-172. Cambridge University Press.

Solie, R. (ed.) 1993. Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Truax, B. 1990. Composing with real-time granular sound. Perspectives of New Music, 28(2): 120-134.

Truax, B. 1992a. Composing with time-shifted environmental sound. Leonardo Music Journal, 2(1): 37-40.

Truax, B. 1992b. Electroacoustic music and the soundscape: the inner and outer world. In J. Paynter, T. Howell, R. Orton and P. Seymour (eds.) Companion to Contemporary Musical Thought, pp. 374-98. London: Routledge.

Truax, B. 1994a. The inner and outer complexity of music. Perspectives of New Music, 32(1): 176-193.

Truax, B. 1994b. Discovering inner complexity: Time-shifting and transposition with a real-time granulation technique. Computer Music Journal, 18(2): 38-48 (sound sheet examples in 18(1)).

Truax, B. 1996. Sounds and sources in Powers of Two: towards a contemporary myth. Organised Sound, 1(1), 13-21.

Truax, B. 1998. Composition and diffusion: space in sound in space. Organised Sound, 3(2): 141-6.

Truax, B. 2000. The aesthetics of computer music: a questionable concept reconsidered. Organised Sound, 5(3), 119-126.

Truax, B. 2001. Acoustic Communication, 2nd edition. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing.

Williams, T. 1977. Androgyne, Mon Amour. New York: New Directions Press.

DISCOGRAPHY

Gay American Composers, vols. 1 & 2, 1996, 1997. CRI CD 721, 750 (some works with electronics).

Oliveros, P. et al. 1998. Lesbian American Composers. CRI 180 (some works with electronics).

Truax, B. 1991. Pacific Rim. Cambridge Street Publishing, CSR-CD 9101 (Wings of Nike).

Truax, B. 1994. Song of Songs. Cambridge Street Publishing, CSR-CD 9401 (Song of Songs).

Truax, B. 1996. Inside. Cambridge Street Publishing, CSR-CD 9601 (Powers of Two: The Artist).

Truax, B. 2001. Twin Souls. Cambridge Street Publishing, CSR-CD 0102 (Androgyne, Mon Amour; In Memoriam A.H.H.; Hymn To The Moon; Twin Souls).

WEBSITES

www.sfu.ca/~truax

www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/su/gaylesb/glgxiv-mus.htmls

See also: Musicworks article,

#108, 2010