Background

(Photo Via Flickr Creative Commons)

Problems

Various humanitarian organizations provided food and basic necessities, but overall health indicators of the internally displaced peoples (IDPs) were not monitored during this time (Schramm et al., 2016). Within these camps, issues such as drug and alcohol abuse, more sedentary lifestyles, poor hygiene, and unsafe sexual practices increasing risks of HIV were prominent, and more concentrated problems (Schramm et al., 2016).

After the peace agreement was signed in 2006, these people were pressured to return to their homes in rural, Northern Uganda (Schramm et al., 2016). Many humanitarian organizations subsequently left, and after twenty years of social, economic, and political instability, the Ugandan government lacked capacity to deal with the sudden disparities in access to much-needed healthcare that many of these former IDPs faced returning to their rural homes (Schramm et al., 2016).

Data Collection

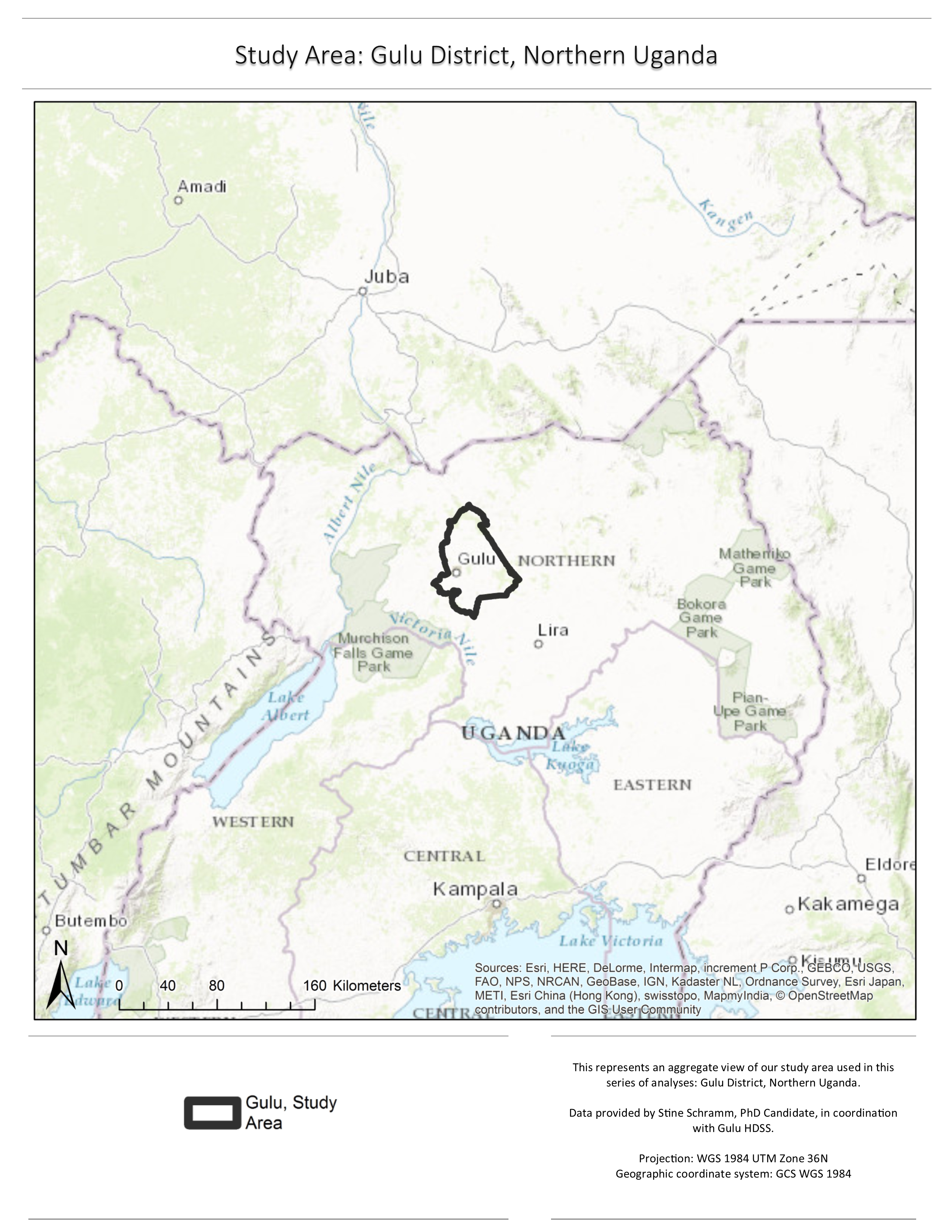

Monitoring and collecting data throughout health facilities in Northern Uganda creates a civil register which incorporates both spatial and temporal elements - health outcomes are connected to households which are measured and recorded over time (Gulu DSS Assistants, 2010). All of this information can help public health researchers document health changes and can help with identifying the poor and the vulnerable.

Thus, the HDSS and the data collected play a role in facilitating positive health outcomes which can build resilience and capacity for a region or nation, and thus aid in post-conflict recovery in Northern Uganda.