REALISM

|

The Gleaners - Jean Francois Millet |

Realism and the Realist NovelRealism is an aesthetic mode which broke with the classical demands of art to show life as it should be in order to show life "as it is." The work of realist art tends to eschew the elevated subject matter of tragedy in favour of the quotidian; the average, the commonplace, the middle classes and their daily struggles with the mean verities of everyday existence--these are the typical subject matters of realism. The attempt, however, to render life as it is, to use language as a kind of undistorting mirror of, or perfectly transparent window to, the "real" is fraught with contradictions. Realism in this simplified sense must assume a one-to-one relationship between the signifier (the word, "tree" for example) and the thing it represents (the actual arboreal object typically found in forests). Realism must, in effect, disguise its own status as artifice, must try and force language into transparency through an appeal to our ideologically constructed sense of the real. The reader must be addressed in such a way that he or she is always, in some way, saying, "Yes. That's it, that's how it really is." Realism can never fully offer up the world in all its complexity, its irreducible plenitude. Its verisimilitude is an effect achieved through the deployment of certain literary and ideological conventions which have been invested with a kind of truth value. The use of an omniscient narrator who gives us access to a character's thoughts, feelings and motivations, for example, is a highly formalized convention that produces a sense of psychological depth; the characters seem to have "lives" independent of the text itself. They, of course, do not; the sense that they do is achieved entirely by the fact that both the author and the reader share these codes of the real. The consensual nature of such codes is so deep that we forget that we are in the presence of fiction. As Terry Eagleton notes, The sign as "reflection," "expression" or "representation" denies the productive character of language: it suppresses the fact that what we only have a "world" at all because we have language to signify it. (136) The realist novel first developed in the nineteenth century and is the form we associate with the work of writers such as Austen, Balzac, George Eliot and Tolstoy. According to Barthes, the narrative or plot of a realist novel is structured around an opening enigma which throws the conventional cultural and signifying practices into disarray. In a detective novel, for example, the opening enigma is usually a murder, or a theft. The event throws the world into a paranoid state of suspicion; the reader and the protagonist can no longer trust anyone because signs--people, objects, words--no longer have the obvious meaning they had before the event. But the story must move inevitably towards closure, which in the realist novel involves some dissolution or resolution of the enigma: the murderer is caught, the case is solved, the hero marries the girl. The realist novel drives toward the final re-establishment of harmony and thus re-assures the reader that the value system of signs and cultural practices which he or she shares with the author is not in danger. The political affiliation of the realist novel is thus evident; in trying to show us the world as it is, it often reaffirms, in the last instance, the way things are. As Catherine Belsey notes, classic realism is "still the dominant popular mode in literature, film, and television drama" (67). It has been denounced as the crudest from of the readerly text, and its conventions subverted and parodied by the modern novel, the new novel and postmodern novel. However, the form, like the capitalist mode of production with which it is historically coincident, has shown remarkable resiliency. It will no doubt continue to function, if only anti-thetically, as one of the chief influences on the development of hypertext fiction. 1993-2000 Christopher Keep, Tim McLaughlin, Robin Parmar. (from: <http:// Realism and the Realist Novel > |

|

Whistler's Mother |

| UNDERSTANDING

THE AESTHETIC OF REALISM IN LITERATURE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY by Dr. Jane Rose First, it is important to understand the aesthetic the came before realism--romanticism. The aesthetic of romanticism, which was popular in the first half of the century, was strongly influenced by Neoplatonic idealism. We see this in several recurring ideas: (1) that true reality is not found in the mutable,

material world. We see this in Edgar Allan Poe's poem Sonnet: To Science: Why preyest thou [science] thus upon the poet's heart, (2) that the soul is immortal and also dwells in all

things. We see this idea in William Wordsworth's poem Ode: Intimations of Immortality: Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: (3) that the goal of art is to transcend the mundane and

the material to express transcendent truth through beauty. We see this idea in John Keats's poem Ode on a Grecian Urn: When old age shall this generation waste, At about the middle of the nineteenth century, the influence of many social forces caused aesthetic taste to change from romantic idealism to realism. Many writers felt that the romantics-- with their focus on the spiritual, the abstract, and the ideal--were being dishonest about life as it really was. The realists felt they had an ethical responsibility to be honest. They felt that the romantic impulse had led to escapist literature that presented life as we wished it to be, but not life as it was.

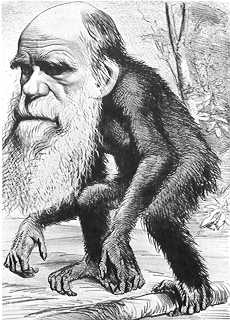

Because this reaction to the earlier romantics was caused in part by changes occurring in their world, and because the realistic writers were trying to depict that world accurately, it is helpful to consider some of the forces at work in the mid-nineteenth century. 1. The industrial revolution had created a society with many new socio-economic problems. 2. Mass production also led to a more affluent, materialistic middle class. 3. Democracy had created a society in which ordinary people were seen as worthy of respect. 4. Increased public education created a more literate society. 5. In Europe, there were revolutions, and serious class issues being contested; in the United States, the Civil War ended slavery, and waves of immigrants created a multi-ethnic society. 6. Women in Europe and the U.S. were challenging their limitations. 7. Technology was transforming countries with railroads and telegraph. 8. Photography gave us a new view of our world. 9. Inexpensive magazine publication brought literature to ordinary people, and made it easier for ordinary people to become published authors. 10. Intellectuals were being stimulated and disturbed by new ideas that were all deterministic:

11. There was an increasing impulse toward social reform in many areas. Realism was more than an artistic aesthetic; it was an ethical position. Realistic writers felt that is was their responsibility to tell the truth about life as it really is, rather than as we wish it to be. As novelist George Eliot, explains in a critical essay, “Our social novels profess to represent the people as they are, and the unreality of their representation is a great evil." 1. Many realists--like Theodore Dreiser, and Leo Tolstoy, and Henrik Ibsen--wished to depict life honestly in the hope that seeing social conditions accurately would lead to improving those conditions. For instance, the demise of a seemingly happy middle-class marriage in Ibsens's play A Doll's House calls into question the highly gendered, patriarchal ideals of the nineteenth century, when Nora explains to her husband why she must leave him to find herself: I went from Papa's hands into yours. You arranged everything to your own taste, and so I got the same taste as you. . . . I've lived by doing tricks for you, Torwald. But that's the way you wanted it. It's a great sin what you and Papa did to me. You're to blame that nothing's become of me. (Act III) 2. Many realists-- like Henry James and Gustave Flaubert--asserting that writers should accept their human limitation and not assume to know an ideal, they felt compelled to remain objective--to depict life as it is, without commenting on it. For instance, Flaubert does not try to make Emma, the title figure of his novel Madame Bovary perfect, but she is also not evil. She is real. He depicts a complicated woman in a complicated situation--an extra-marital love affair has led her to be withdrawn from family into her private world. His challenge is to present the realities of this human drama without judgment. In scenes like the one below, he dares to depict dramatically an ambivalence that leads Emma to less-than-ideal behavior for one in that most idealized role--mother: "Let me alone!" Emma cried, thrusting her [toddler daughter] away. The expression on her face frightened the child, who began to scream. "Won't you let me alone!" She cried, thrusting her off with her elbow. Bertha fell just at the foot of the chest of drawers, cutting her cheek on one of its brasses. She began to bleed. Madame Bovary rushed to pick her up, broke the bell-rope, called loudly for the maid; and words of self-reproach were on her lips when Charles [her husband] appeared. "Look what's happened, darling," she said, in an even voice. "The baby fell down and hurt herself playing." (Bk. II: Chap.4) The writing of the realists reflects a shift in values from the idealism of the romantics. The list of characteristics below are not necessarily present in all realistic texts, but they show common ways that realistic values changed literature. 1. Realism

focuses on the common, everyday life of average, ordinary people here and now. Theodore Dreiser's novel Sister Carrie, for instance, opens with a

scene being enacted daily in the last decades of the nineteenth century as young people

sought opportunity in the burgeoning cities: When

Caroline Meeber boarded the afternoon train for Chicago, her total outfit consisted of a

small trunk, a cheap imitation alligator-skin satchel, a small lunch in a paper box, and a

yellow leather snap purse, containing her ticket, a scrap of paper with her sister's address in Van Buren Street, and four

dollars in money. It was in August, 1889. She as eighteen years of age, bright, timid, and

full of the illusions of ignorance and youth. In The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Leo Tolstoy makes his protagonist's ordinariness

thematic when he declares, "Ivan Ilyich's life had been most simple and most ordinary

and therefore most terrible" (Chap. 2). This

is very different from the romantic novels, like Sir Walter

Scott's Ivanhoe, stories of

idealized heroic knights and pure damsels and in long-ago time. 2. Authors of

realistic fiction see themselves as scientists. As the French novelist Emile

Zola explained, they tried to write "scientifically" by inventing realistic characters,

placing those characters in realistic situations, then imaginatively recording how those

characters realistically responded. A classic

example of this technique is seen in Stephen

Crane's The Red Badge of Courage, which is not a book thematically

focused to condemn or celebrate war, but simply to examine what can happen to a young man,

reared on heroism and patriotism, when submitted to the real horrors of battle: The

youth had been taught that a man became another thing in a battle. He saw his salvation in

such a change. Hence this waiting was an ordeal to him. . . . He wished to go into battle

and discover that he had been a fool in his doubts, and was, in truth, a man of

traditional courage. The strain of present circumstances he felt to be intolerable. (Chap.

3) But battle, when it comes, is

not what he has expected: His

impotency appeared to him, and made his rage into that of a driven beast. Buried in the

smoke of many rifles his anger was directed not so much against the men whom he knew were

rushing toward him as against the swirling battle phantoms which were choking him. (Chap.

5) This is very different from

the idealized "romances,"

like Nathaniel Hawthorne

's Scarlet Letter, in which characters and situations

are constructed to illustrate abstract human qualities. 3. Most

realists attempt to provide an objective reproduction of life. They use descriptive language

to describe sights and sounds, creating a texture that suggests meaning, but they avoid

explaining the meaning or interpreting the significance of a scene. Edith Wharton's novel The Age of

Innocence immerses the reader

in the material opulence of New York's elite. Entire paragraphs are spent directing the

reader's attention to telling atmospheric details, as is the case in this description of

the opera stage in the opening chapter: The foreground, to the footlights, was covered with emerald green cloth. In the middle distance symmetrical mounds of woolly green moss bounded by croquet hoops formed the base of shrubs shaped like orange-trees but studded with large pink and red roses. Gigantic pansies, considerably larger that the roses, and closely resembling the floral penwipers made by female parishioners for fashionable clergymen, spring from the moss beneath the rose-trees; and here and there a daisy grafted on a rose-branch flowered with luxuriance prophetic of Mr. Luther Burbank's far-off prodigies. This is very different from

the symbolic, mood evoking descriptions of romantics like Edgar Allan Poe, which are to be

affecting but not depicting. 4. They often

use dialect to depict real, ordinary speech. They take great pain to

reflect the way a characters from a certain region would truly speak. While we think of Mark Twain as a realist in his social satire, we

are less aware of his desire for regional accuracy in speech. When he wrote The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,

Twain was aware that readers might wrongly approach this novel as another "boys book." To prepare his readers for novel's

careful attention to dialect, he begins the novel with this note: In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods South-Western dialect; the ordinary "Pike Country" dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a hap-hazard fashion, or by guess-work; but pains-takingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech. Twain's concern that readers

"would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not

succeeding" is the concern of a realist. Because

of its focus on flawed actuality, the material present, the prosaic, the aesthetic

of realism has not stimulated much great poetry. But in the stylistic innovations of Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself," we see the realist's grounding in

ordinary speech about ordinary subjects: The

butcher-boy puts off his killing-clothes, or sharpens his knife at the stall in the

market, I

loiter enjoying his repartee and his shuffle and breakdown. Blacksmiths

with grimed and hairy chests environ the anvil, Each

has his main-sledge, they are all out, there is a great heat in the fire. (St. 12) This poem illustrates a change

from the elevated language that marks traditional verse and prose as "literature." 5. Realists

are often impelled by the urge for social reform. They attempt to expose situations in order to change them. When Rebecca Harding Davis opens her story Life in the Iron-Mills, she expresses this desire, shared by many realists, to disabuse her genteel readers of their smug innocence. She want us to know what life in America is like for immigrant laborers: A cloudy day: do you know what that is in a town of

iron-works? . . . The air is thick, clammy with the breath of crowded human beings. . . .

I want you to hide your disgust, take no heed to your clean clothes, and come right down

with me,--here into the thickest of the fog and mud and four effluvia. I want you to hear

this story. . . . I want to make it real to you. 6. Realists

focus on people in social situations that often require compromise. They develop characters that are unheroic--they are flawed, and often cannot be "true to themselves." William Makepeace Thackery gaves his novel Vanity Fair the subtitle "A Novel without a Hero," and George Eliot's novel Middlemarch, subtitled "A Study of Provincial Life," shows with the life of Dorothea Brook that people of noble ideals are compromised by the imperfect society they dwell in. This is particularly true for women, who can only achieve social and economic status through marriage. Using Saint Theresa as a model of the ideal, Eliot explains, Many

Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life. . . perhaps only a life of

mistakes . . . perhaps a tragic failure which found no sacred poet and sank unwept into

oblivion. With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and

deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere

inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent

social faith and order. . . . (Prelude) The poet Robert Browning's dramatic monologues reflect the realistic impulse. His speakers ironically reveal their own very natural human frailties. For example, the friar in "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" shows the way petty jealousy has compromised his ideals and led to hypocrisy: Gr-r-r--there

go, my heart's abhorrence! The aesthetic of realism

rendered the terms "hero" or "villain" inappropriate. Unlike Charlotte Bronte's

Jane

Eyre or Charles Dickens's David Copperfield, protagonists in realistic

novels often cause their own problems, or accept compromised solutions to them. 7. While

realists emphasize external, material reality, they also recognize the reality complex of

human psychology. Their characters are

complicated personalities, whose individual responses to situations are influenced by many

external and internal factors. Henry James's fiction is extremely psychological, both in

his treatment and in the character's proclivities. His highly sophisticated characters

constantly play mind games, and analyzing nuances of speech and gesture. Daisy Miller:

A Study, is not just a study of Daisy, an ingenuous young American who fails to

understand European society; it is also a study of how the cosmopolitan Europeans are not

prepared to understand her. The close examination of Winterbourne, a neglected suitor,

shows James's focus on the psychological dimensions of the drama: He

had perhaps not definitely flattered himself that he had made an ineffaceable impression

upon her heart, but he was annoyed at hearing of a state of affairs so little in harmony

with an image that had lately flitted in and out of his own meditations; the image of a

very pretty girl looking out of an old Roman window and asking herself urgently when Mr.

Winterbourne would arrive. (Chap. 3) |

Honore Daumier The Third Class Carriage |

Literature and Philosophy Revisited

It is not my intention to suggest that we

must choose between art and philosophy, but it has been argued that art is capable of

achieving the same valuable goals as philosophy, such as finding ways to live and learn. I am suggesting that literature by virtue of its

form may achieve this in deeper and wider ways than philosophy. However, to do justice to the field of philosophy,

we may add to Murdoch’s comments that perhaps literature is just more accessible to

the average person; that we are more accustomed to learning from stories and require less

specialized training to grasp the ideas encoded there.

That said, there are many crucial philosophical ideas that are naturally

explored in literature and after a certain point in these types of novels, it is often

impossible to distinguish which is the literature and which is the philosophy, they are so

complimentary. Examples of this are the great

works of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, which I will discuss later. Perhaps ultimately it is simply the layman’s

preference to have complex philosophical concepts presented in literary form so as to make

them more comprehensible. Today an author cannot write in the same manner as the nineteenth century authors. It comes down to the relationship to characters. There has been a moral change, Murdoch (27) informs us, and modern writers are more ironical and less confident. No longer can a writer impose her direct judgment or authority over the work in the omniscient voice of the past. This coincides with Taylor’s view of authenticity and not wanting to judge other lifestyles. Murdoch confirms this by blaming the disappearance or weakening of traditional religion in the West, perhaps the greatest change over the last one hundred years. The major nineteenth century novelists like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky took their belief for granted. Another reason for a shift in the moral voice is the loss of a social hierarchy, which undermines a person’s sense of belonging and makes judgment more diffident. (27). Tolstoy (1828 – 1910)

Of the writers we shall examine, Tolstoy was possibly the most torn between

literature and philosophy. His life splits in

two parts – first, as the author who wrote titanic novels that defined the form of

realist fiction, and second, as the prophet of personal and social vision, the moral and

religious teacher who taught non-violence and influenced Gandhi.

Born into the most aristocratic of families, Count Tolstoy was orphaned as a child

and raised by his aunts. He was tutored at

home and then began studies at university, starting with oriental languages, changing to

law and finally dropping out and joining the military.

He was compulsive about keeping a diary, and even the early entries focused on

self-analysis. From a young age, there was a

polarity to his thinking; he wanted to live a moral life and searched for rules to live by

but his repeated failures to live up to his self-imposed standards led to the belief that

life is too difficult, random and complex to adhere to a rigid code of behavior or

philosophical system.

His first stories were written about his childhood and about the suffering of

soldiers during war in one of the earliest stream of consciousness styles that later

influenced Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. Tolstoy

declared that although he loved all his characters, most beautiful to him was the truth. This would later be the reason he divided from

Shakespeare. His literary success did not lead to his joining an intellectual camp and the Russian literati spurned him as an outsider. Tolstoy became interested in pedagogy, and through his life, experimented with various schools. He published a reading primer that was widely used, and even started a school for peasants in his home town. His marriage and 13 children settled him on his estate and he began the labor of writing his great novels.

Bloom takes umbrage at Tolstoy’s essay, What is Art? and calls it a ‘disaster’. He claims it is Tolstoy’s rebellion

against the aesthetic, and in particular, “his spiritual revulsion against the

immoral and irreligious tragedy of King Lear.” (Bloom, WC 58). Tolstoy wanted to Christianize the

bard’s pre-Christian plays. It has been

noted that Shakespeare was neither a Christian nor a moralist and, in comparison to the

inferior later works of Tolstoy, we can appreciate that some of the power in Shakespeare is due to a freedom from

moral and religious tendentiousness. (58). Ironically,

the composer Bach also failed Tolstoy’s test for what could be delivered as good and

simple to the people as an example of Christian moral art, as did the Greek tragedies,

Dante and Michelangelo. Tolstoy claimed to be

a champion of the truth, but Shakespeare, for one, was not interested in the truth.

And yet there must have been at least a few doubts in Tolstoy’s mind. Hadji

Murad , the masterful novella he wrote very late in his career but left unpublished,

contradicted nearly all of his principles of religious and moral ideals. The character of Hadji Murad lives and dies as

the ancient epic hero, culling together the qualities of Odysseus, Achilles and Aeneas,

and greatly influencing Hemingway’s character in For Whom the Bell Tolls.

(336-37). Hadji Murad is Shakespearean in

character, and free of pity, rage and desire. That

Tolstoy could conceive of this character is reassuring for his aesthetic reputation. (348-49).

Sadly, at the end of his life, Tolstoy became more and more dogmatic and his once

happy household dissolved in misery. He died

in a railway station, metaphorically-speaking, trying to escape from the irreconcilable

differences between his art and his religion. He

had discovered his nihilism and his inability to abide nihilism. (333).

In literature, he will remain the symbol for the search for the

meaning of life. We shall now have a look at

another author who wrote in the realist tradition; one who became famous for an analysis

of the moral imagination. George Eliot (1819 – 1880)

George Eliot, the pseudonym of Mary Ann Evans, was doubly formed by her first

society. Raised religiously in a village in

the Midlands, she was sent to Protestant boarding school where she did well but returned

home to keep house for her conservative father when her mother died. Fortunately they moved to a larger town and she

came into contact with several families who not only expressed their religious doubts but

enlarged her social circle to include free thinkers.

It was this change that directly led to her break with religion and also allowed

her to escape the provincialism of her younger years.

When her father died, she obtained a job as a freelance writer through other

friends in London where she began editing a weekly magazine and lived an unusually liberal

life for her times.

Initially a critic and a translator, she soon began to write novels. Middlemarch is regarded as her masterpiece

and she is given credit for having developed the novel from “mere entertainment to a

highly intellectual art form”. (Britannica

CD ROM). She writes in the realist tradition

and includes all classes of human beings, from the landed gentry and clergy, to

shopkeepers and publicans, farmers and laborers. By

applying scientific analysis of the internal processes, she examines social and individual

existence.

Nietzsche criticized Eliot for banishing God from her writings but preserving Christian morality. This was Nietzsche’s

error – Eliot’s morality owed a debt to Wordsworth’s view on life. They both elevated the same sense of pure, natural

human relations, a vision of pastoral man and woman as the essence of goodness. Renunciation to Eliot meant an aesthetic and moral

goodness that in modern terms we might call the sublime in “human nature” –

manifest as the solitary figure who is yet open to others.

In this, Eliot is more closely affiliated with the Romantics. (321).

Eliot is most definitely not a philosopher; she is the novelist as thinker, like

Shakespeare, like Emily Dickinson. And like

these authors, “she had to re-think everything for herself.” She tends to be misunderstood because her

cognitive strengths are underestimated. The

combination of her “perspectivizing” and moral insights frees her from an

extreme self-consciousness that would prevent her from judging her own characters so

wisely. (322).

AestheticsTolstoy, in his essay, “What is Art?” rejects the idea that we ought to be satisfied only by the beauty in art. If the apprehension of beauty inevitably leads to pleasure, he says, then pleasure must be the goal of art. We know from other philosophical writings that Tolstoy was convinced that there needs to be at least a social dimension to art, such that the artist and audience will to come to understand one another’s feelings and attitudes in a negotiation of the experience. (Lyas 61). But this view falsely assumes the artist has said feelings to begin with, and undervalues the work of art as object, as well as assuming the audience will arrive at the same feelings as the artist. I feel that this view of transmitting meaning from creator to audience implies a right and wrong way of experiencing art. In addition, it ultimately professes that the artist has an intention in putting the work out there. It is often true that the artist will shape or point at clues to guide the audience to certain ideas in the work but there are still limitless interpretations available. In other words, there is nothing concrete about quality art. It is critical to distinguish between the act of entering the emotions, thoughts and attitudes of a work and another to believe it is possible or desirable to adopt the artist’s own sense. The extent to which we inhabit a story depends on our emotional and cognitive investment in it. In the end, however, our impressions of it will remain subjective due to who we are. Lyas (66) states that it may grip us, exercise an absolute claim on us, but the “purpose” of art is not to provide a historical or common truth. Art stands on its own. It is everything and anything. It also has the freedom to mean nothing. If Hamlet tells us anything, it tells us about Hamlet the individual, his specific circumstances, not about life in general. A work’s objective is to single out a particular idea and make it explicit. If it has truth in it, we cannot judge; it can only be generally true and for that matter we can say the experience of works of art transcends judgment. Think of Shakespeare, Homer, Tolstoy. It is the transcendence in their art that we feel; and our inadequate labels of “good” and “bad” seem petty. If a “novel of ideas” is lacking in art, perhaps it is because it belongs to another form. And yet, if it is good art, then the ideas appear to be smoothed into oneness with the work and fall into a rhythm of narration and reflection, narration and reflection, such as in War and Peace. In “What is Art?”, Tolstoy explains ideas in such a way that they embody the highest perceptions of his era. For him the measure of good art is akin to religious rapture and he effectively expounds religion through art to his generation. One of the best examples of “purpose” subordinated to the aesthetic is found in Dickens. His social reflections are aesthetically valuable, Murdoch (21) states, since they are grounded in character; that is, with substructures that are not abstract. The guiding principle remains founded upon art. Although Dickens had specific social targets and did indeed instigate change, he was still a most imaginative writer first while being a social critic second. It was likely that the corruption in society most strongly spurred his imagination and creativity. The reason his novels are so effective is because he is able to portray living, breathing characters in their frightful, David Copperfield-like situations. (17). Dickens allows his characters to speak directly to us and we as thinking, feeling readers identify strongly with them. Through this literary experience, I feel we become socially aware on our own, without being preached at or threatened. Awakening to new ideas in this subtle manner is probably the main thrust of the power of art. (comprised of excerpts from Barber, Immediacy and "Writer and Society")

|

Francisco de Goya - A Village Bullfight |