By Daniela Balanzátegui and Ana María Morales, in collaboration with CONAMUNE and GAD La Concepción

Over the last two decades, some South American archaeologists who are promoting decolonizing and critical perspectives have pointed out that the archaeological study in the Andean region is largely focused on the pre-Hispanic past.

By emphasizing the history of white-mestizo and pre-colonial indigenous heroes as the symbols of the Andean nations, archaeology has supported the racial marginalization of modern Afro-descendants and Indigenous peoples (Gnecco 1999, 2002; Singleton and de Souza 2009; Wade 1997). Unfortunately, few archaeologists have been interested in the history of post-contact indigenous and mestizo populations (Balanzátegui et al. 2016). Even less has been said about the material culture of the African Diaspora in Ecuador. Afro-Ecuadorian material expressions, traditional knowledge, and cultural practices have also suffered processes of blanqueamineto (“whitening”) and appropriation in order to become part of the national heritage. In this context, the destruction, exclusion, and removal of the Afro-descendant past from Andean history raise questions about the larger socio-political structure. Who defines what narratives of the past matter? Which archaeological remains are important to preserve? And whom does this heritage represent?

In this blog, we summarize the results of three years of work on a collaborative archaeology and anthropology initiative in La Concepción, Afro-Ecuadorian Ancestral Territory of the Chota-Mira Valley[1]. The project supports recognition of the Afroecuadorian past and a process of reparations based on historical injustices related to slavery, loss of land, psychological trauma. This collaborative initiative involves intercultural discussions about the Afro-descendant experience of their heritage, community-driven guidelines for managing heritage, and an examination of the place of academic production within traditional ways of interpreting the past and material culture. Here, we discuss relationship-building with the Afro-Ecuadorian community of La Concepción and our role, not just as scholars, but also as collaborators in a long-term process of historical reparation.

The Afro-Ecuadorians[2] in La Concepción

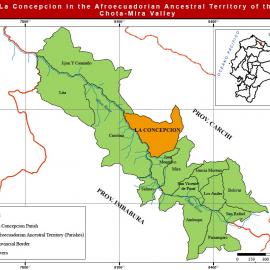

La Concepción Parish is located in the Chota Mira Valley that lies between the provinces of Carchi and Imbabura in the Northern Highlands of Ecuador (Figure 1, above). Around 25,400 Afro-descendants live between both provinces and correspond to 2.06% of the total Afro-Ecuadorian population[3]. The parish includes 18 communities in which a majority of the population self-identifies as Afro-descendant, with the community of La Concepción as the administrative and political centre of the parish. Historically, La Concepción was the largest 18th-century Jesuit hacienda of the Chota-Mira Valley where the majority of the enslaved population worked in the cultivation and processing of sugar cane (Bryant 2005; Coronel 1991). The Jesuits were expelled in 1767 from the Royal Audience of Quito, resulting in instability within the Afrodescendant families who were mistreated by the new owners of the haciendas. The enslaved population resisted enslavement by many means, including strategies like cimarronaje (runaway organized communities), revolts, and commemoration of their African past.

The system of slavery officially ended in 1852, however, elders interviewed from La Concepción confirmed that the system of exploitation continued until 1964 when the peasants, both indigenous and African descent, finally achieved recognition of their right to be owners of their lands and free from any work or debts to the hacienda owners. Nevertheless, with the abolition of slavery and the formation of the Ecuadorian nation, Afro-descendant population continued to suffer from racial discrimination and social marginalization based in colonial precepts. In 1998, Afro-descendant rights as Ecuadorian citizens were recognized in the National Constitution. In recent years, their cultural heritage has been nationally acknowledged in several ways, the result of efforts of Afro-Ecuadorian political movements and leaders.

Building bridges: First Dialogues (2012–2013)

In 2011, anthropologists Ana Maria Morales and Victoria Maldonado started an ethnohistorical investigation about a 1940 train station town, named Estación Carchi, located in La Concepción. They researched the participation of Afro-Ecuadorians in the construction of the Ferrocarril del Norte (“Train of the North”) connecting the Coast and the Highlands of Ecuador, a remarkable symbol of early 20th-century Ecuadorian nation-building.

The next year, we began our project with the Afro-descendant communities in La Concepción looking for better ways to address our mutual interests in investigating an African Diaspora past. When we arrived in La Concepción in 2012, Daniela’s doctoral investigation centred on the archaeology of the African diaspora in Ecuador, became the main focus of this project. We initially approached the representatives of the community in order to find out how we could build this study of the past using archaeology and anthropology as complementing sources of analysis.

The authorities of La Concepción are organized as a rural parish, politically administrated by what is known as a Decentralized Autonomous Government (GAD in Spanish). An elected president and a committee of representatives govern the La Concepción GAD. They welcomed our research and since then have supported our proposals. In 2012, we mainly worked with the representatives developing an initial proposal integrating topics that the community was interested in exploring. Recognizing that Daniela’s time in Ecuador was limited by her doctoral studies in Canada, we agreed with the GAD to mainly work during two seasons of May-September 2013 and May-November 2014. The rest of the year, Ana Maria continued to visit the community and further her historical and ethnographic investigation about Estación Carchi.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012: 118) has written much about the importance of how research problems are conceptualized and designed, how the community and its members participate, and what the research means for the participant including its implications. Such a methodology of collaborative archaeology and anthropology, which is fundamental to achieving our project goals, has been employed over the course of these three years. The archaeological investigations at La Concepción required efforts to build trust and respect between the parties. As researchers, we were open to modifications to address issues brought up by community members and leaders. These first steps resulted in a constructive way to design questions and discuss our own archaeological and anthropological methodologies relative to community interest and needs.

One of the main concerns brought up in conversation within the socializaciones was related to the intellectual property of the proposals, projects and results. The community had doubts about our intentions because previous non-Afro-descendant investigators were intrusive and did not contribute to cultural and historical reparations. The elders insisted they did not want to share their history if the traditional knowledge was to be used only for the personal interests of the researchers. Acknowledging this concern, we asked the community and their representatives to share with us the authorship of proposals, projects and investigations; we now specify authorship by indicating “In collaboration with,” such as is used for this article. Workshops carried out with young leaders, as well as conversations and debates with community representatives and elders have been incredibly informative for us.

When the 2013 fieldwork season started, our main concern was the slow integration of Afro-descendant community members in archaeological surveys. This was due to the fact that participating in the project would interfere with their agricultural work. With the authorization of La Concepción GAD, we decided to bring in archaeological volunteers— our Ecuadorian and Spanish colleagues— which gave us more time to focus on our work with the community and to continue workshops with the elders, community representatives and young leaders. The volunteer group formed by four graduate students from social sciences and education, along with members of the community, developed a workshop for local children with the theme “Imagine yourself as an archaeologist” (Figure 2). By the end of the season, the successful archaeological surveys allowed us to identify places to continue investigating in dialogue with the community.

Fig 1., at top, Location of La Concepción Parish in the Afroecuadorian Ancestral Territory of the Chota-Mira Valley. Fig. 2, above, Wilson Delgado teaching about artifact classification during the family workshop “Imagine yourself as an archaeologist,” La Concepción, 2013. All images courtesy of Daniela Balanzátegui, used with permission.

The Meaning of Collaboration: The CONAMUNE (2014-2016)

During the first year of the project in 2012, there were challenges in developing a relationship with the community. We thus began our second phase of work better understanding the importance of intercultural communication, and of sharing knowledge and experiences from both sides. From this standpoint, archaeological research becomes a shared practice. In 2014, once the community had a clearer understanding of our objectives and long-term commitment, a family and three young men decided to work with us in the archaeological excavations, in an effort to protect and manage their own heritage (Figure 3).

Fig 3. Community collaborators and Zooarchaeologist, Ibis Mery, excavating the Teresa Montero site, La Concepción, 2014.

During the second fieldwork season, we also continued our community meetings. We also started working with an Afro-Ecuadorian Women Organization called CONAMUNE (Coordinadora Nacional de Mujeres Negras-Carchi), created in 1999, that undertakes political action for the protection and reinforcement of Afro-Ecuadorian women and community rights. Our relationship with CONAMUNE was enriched by our shared interests and actions, such as heritage commemoration, inter-cultural learning, and the eradication of racism.

The revitalization of Afroecuadorian identity is one of the CONAMUNE’s main goals (2003; 2015). The CONAMUNE, along with other stakeholders, developed an ethnoeducation program in the Chota-Mira Valley that works with Escuela de la Tradición Oral la Voz de los Ancestros (Oral Tradition School of the Voice of the Ancestors). Ethno-education is described as the process of teaching and learning casa adentro (“within-home”) from an Afro-descendant perspective for the Afro-descendant communities, and as the next step, casa afuera (“out-home”), sharing their history with others (Pabón 2007). Our community conversations reinforced the importance of translating complex academic language and creating a framework where different ways of comprehension are valued. This must be seen as a form of decolonizing knowledge.

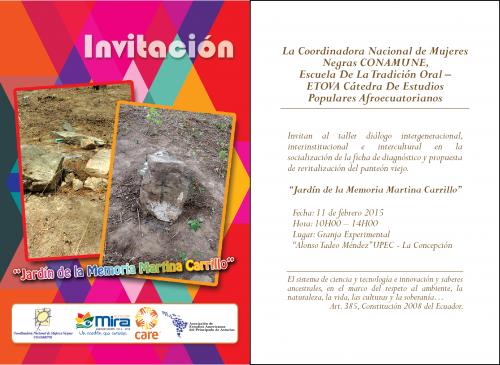

As a consequence of these dialogues, CONAMUNE proposed the elaboration of a project to protect and research an 18th-century cemetery, used until the early 20th century and then abandoned. This sacred place, where the ancestors of the Afro-descendant communities of La Concepción rest, has been named Jardín de la Memoria Martina Carrillo (Garden of the Memory Martina Carrillo). The cemetery was named for an 18th-century enslaved woman from La Concepción, who escaped from the hacienda and later sued the owners for their mistreatment of the families of La Concepción.The proposal to revitalize and commemorate this remarkable place for the African Diaspora heritage in Ecuador was lead by Barbarita Lara and Olga Maldonado (CONAMUNE), Daniela Balanzategui, and Ana María Morales.

Within the project of the Jardín de la Memoria Martina Carrillo, a methodology was proposed by CONAMUNE which called for collective work, or minkas (Andean indigenous name for community work). These minkas, which brought together people from the community, CONAMUNE leaders, the research team and the Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi, involved cleaning the graveyard to make the tombs visible and to define the area of the cemetery archaeologically (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Minka at Jardín de la Memoria Martina Carrillo. Barbarita Lara (CONAMUNE), David Carcelén (community collaborator), Daniela Balanzátegui and Manuel Siguenza (archaeologists), La Concepción 2014.

Ana María Morales, with a research team formed by three young men, interviewed the elders of the community. CONAMUNE also organized workshops with elders to better understand the history of this sacred place.

In February 2015, a major presentation of the proposal to recuperate the cemetery was made. The project was presented to different Afro-Ecuadorian organizations, NGOs, community leaders, regional and national authorities, and people from La Concepción in a large assembly (Figure 5). This meeting contributed to the growth of the proposal into a long-term project including the physical recuperation of the cemetery, the creation of an interpretation centre, and a ceremonial centre.

For this project, we used IPinCH publications and website resources, particularly the “Declaration on the Safeguarding of Indigenous Ancestral Burial Grounds as Sacred Sites and Cultural Landscapes,” to better address the position of the Afro-descendants to safeguard this cemetery. The archaeological practices employed at the African Burial Ground in New York and the Cemetery of Pretos Novos in Rio de Janeiro, as well as Blakey’s ethical and epistemological viewpoints about the study of human remains and cemeteries (Blakey 2008; Roberts and McCarthy 1995), also aided our research. The comparative examples from the Americas helped us to define some parameters for a more ethical approach to the archaeological study of African Diaspora “culturally, spiritually and politically sensitive sites”(Leone et al. 2005).

Fig. 5. Invitation elaborated by CONAMUNE for the February assembly that includes national Afroecuadorian movements and organizations, La Concepción, 2015.

All of these activities constitute part of what Katzer and Samprón (2011) have called a collaborative ethnography: a performance of mediation, sharing of different views and building “a multi-situated network of reflexive subjects.” Here ethnography becomes a narrative style that produces knowledge (2011:61). This knowledge is constantly re-configured by interdisciplinary dialogues between political leaders, the researchers and the community members. The product of this kind of communal work and research is a different construction of—and political action towards—heritage. Our research methodology, born out of the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology, is also the result of individual, collective, and historical narratives contributed by the community.

Future Challenges

Three years ago we arrived in La Concepción to practice an archaeology that was thought to be “conflictive, subjective, and historically irrelevant.” What we found was a community that opened their doors to working collaboratively, and invited us to reconsider our anthropological and archaeological knowledge and learn from deep intercultural dialogues. We increasingly feel that the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology really matter because they are actively supporting a process of historical reparation, social justice, and recognition. After three years, this is only the beginning of our relationship with the community of La Concepción.

Collaborative archaeology and anthropology have promoted the recognition of Afro-Ecuadorian tangible and intangible heritage that was previously ignored, hidden, and erased from official histories and heritage declarations. We expect that the strong relationships we have developed may generate transformations in national and international debates around why the heritage of some marginalized groups matter more than others, and a reconsideration of the place of African Diaspora heritage in the Americas.

The United Nations declared 2015-2024, the “Decade of the Afrodescendants” (2015-2024), a key time for recognition, social justice, and historical reparation. With these goals in mind, we will continue to support local interests with our archaeological and anthropological research, particularly the cemetery revitalization and the Estación Carchi project. We also expect to collaborate on ethno-education curricula, translating the academic results from our projects into more useful educational materials for different audiences.

Daniela Balanzátegui is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University and an IPinCH Associate.

Acknowledgements

We thank CONAMUNE, La Concepción GAD, UPEC (Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi), Delgado-Gudiño family, the 2013-2014 Research team and volunteers, Dr. Gretchen Hernandez, and the IPinCH team for this opportunity.

References Cited

- Balanzátegui, Daniela, Ross W. Jamieson, and Florencio Delgado (editors). 2016. Arqueología Histórica del Ecuador, edited volume, Universidad San Francisco de Quito and Simon Fraser University, Quito, in press.

- Blakey, Michael L. 2008. An Ethical Epistemology of Publicly Engaged Biocultural Research. In Evaluating Multiple Narratives: Beyond Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist Archaeologies, edited by Junko Habu, Clare Fawcett, John M. Matsunaga, pp. 17–28. Springer, New York.

- Bryant, Sherwin Keith. 2005. Slavery and the Context of Ethnogenesis: African, Afro-Creoles, and the Realities of Bondage in the Kingdom of Quito, 1600-1800: The Ohio State University. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Ohio.

- Coronel, Rosario. 1991. El valle sangriento de los Indígenas de la coca y el algodón a la hacienda cañera jesuita: 1586-1700. Quito: FLACSO-Sede Ecuador y Ediciones Abya-Yala.

- Edwards, Brent Hayes, Cheryl Johnson-Odim, Agustín Laó-Montes, Michael O. West, Tiffany Ruby Patterson, and Robin D.G. Kelley. 2000. “Unfinished Migrations”: Commentary and Response. African Studies Review 43(1): 47–68.

- García, J. 2010. Territorios, territorialidad y desterritorialización. Un ejercicio pedagógico para reflexionar sobre los territorios ancestrales. Quito, Fundación Alotrópico.

- Gnecco, Cristóbal. 1999. Archaeology and Historical Multivocality. In Archaeology in Latin America, edited by Gustavo Politis and Benjamin Alberti, pp: 266-279, Taylor and Francis US, London and New York.

- Gnecco, Cristóbal. 2002. La indigenización de las arqueologías nacionales. Convergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales (27): 133-149.

- Leone, Mark P., Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, and Jennifer J. Babiarz. 2005. The Archaeology of Black Americans in Recent Times. Annual Review of Anthropology (34): 575–598.

- Pabón, Iván. 2007. Identidad afro: procesos de construcción en las comunidades negras de la Cuenca Chota-Mira. Editorial Abya Yala.

- Roberts, Daniel G., and John P. McCarthy. 1995. Descendant Community Partnering in the Archaeological and Bioanthropological Investigations of African American Skeletal Populations: Two Interrelated Case Studies from Philadelphia. Wiley-Liss, New York.

- Katzer, Leticia and Agustín Samprón. 2011. El trabajo de campo como proceso. La etnografía colaborativa como perspectiva analítica. En: Revista Latinoamericana de Metodología de la Investigación Social (2):59-79.

- Singleton, Theresa, and Marcos André Torres de Souza. 2009. Archaeologies of the African Diaspora: Brazil, Cuba, and the United States. In International Handbook of Historical Archaeology, edited by Majewski, Teresita, and David RM Gaimster, pp. 449–469. Springer, New York.

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies. Zed Books, London.

- Wade, Peter. 1997. Race and ethnicity in Latin America. Vol. 3. Pluto Press, London.

[1] In Ecuador, Afroecuadorian political movements have recognized two Ancestral Territories. One that is located in the Chota- Mira Valley where the enslaved Africans and their descendants arrived since the 15th century. The other is located in the northwest coastal province of Esmeraldas that continues through the Pacific Ocean, including the Afro-Colombian communities (Garcia 2010).

[2] The terms “Afro-descendant” and “Afro-Ecuadorian” are ethnic and political identities recognized under the Ecuadorian Constitution, but mainly by the Afro-Ecuadorian political movements, leaders and civil society. Both terms make reference to politics of difference and a conception of world history that treats the African diaspora as a unit of analysis (Edwards et al. 2000, Patterson and Kelley 2000).

[3] Resultados Autoidentificación de Población del Censo 2010, CPV 2001 y 2010. CODAE