Repatriation can be an opportunity to teach, learn and remember for future generations (Krmpotich 2010; 2014; Nahrgang 2002).

Drawing on my experiences with the return of the Rickley Collection in 2014, I reflect on the repatriation process in the Canadian context and offer some key lessons learned that may be useful for future, small-scale repatriation efforts. These lessons reinforce the importance of in-depth analyses of repatriation cases for a broader understanding of this complex and highly localized process.

The Rickley site, located in southwestern Ontario, was brought to the attention of the University of Windsor in the late 1960s. There, in 1974 and 1975, the university leased an area of field from a local farmer for the location of an undergraduate archaeology field school. The field school ran for two seasons, with the classes discovering many artifacts but also a number of human burials on the site. The final discovery of a circular formation of six cremated bundle burials marked the end of the excavation. Soon after that, the field school program was terminated due to selective looting and the lack of authoritative action rectifying it (Kroon 1975).

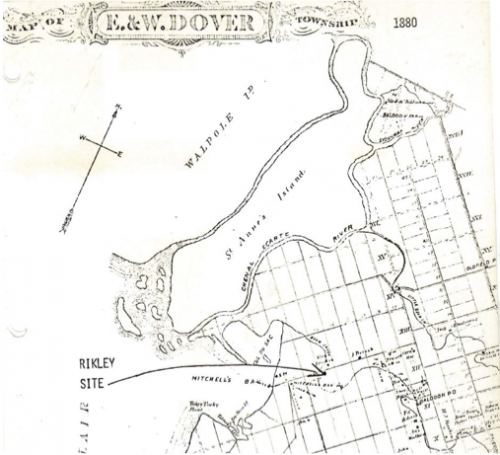

(Top left). One of the artifacts that went missing from the Rickley site was a unique birdstone. It has never been recovered; (above) Map of Dover Township, Ontario where the Rickley site is located. Images used with permission of the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Windsor.

Much of what transpired during the excavation has been obtained from unpublished student accounts and the official site report (Kroon 1975). There is little information as to how the human remains from the Rickley site were received by the Anthropology Department at the University of Windsor, but it was noted that the circular bundle burial was re-interred with some ceremony (Kroon 1975). The rest of the remains are assumed to have been curated and briefly used for teaching, before being boxed and largely forgotten.

In the early 2000s, the collection was re-discovered by a newly hired physical anthropologist, Dr. John Albanese, who contacted Russell Nahdee at the Aboriginal Education Centre on campus. Together they consulted with Walpole Island First Nation, then the closest recognized First Nation to the University of Windsor and to the site itself. Contemporary archaeological policies for Ontario guided their actions, though the consultation practices outlined by government policy are intended primarily for current excavations rather than for collections of remains held for 30+ years (Ontario 2011). One of the first agreed upon tasks was to extensively inventory and catalogue the collection and associated documents.

In 2013 the university administration became involved and a committee was established with the Walpole Island First Nation to discuss the next steps. Ultimately the final decision to rebury the remains held in the Rickley Collection came in the spring of 2014 and subsequently, invitations were extended to local First Nations, to several U.S. tribes, and to the non-Indigenous stakeholders, to rebury the remains on Walpole Island in the early days of summer.

Legacy Collections

Archaeological data collected during the mid-20th century was often recorded sporadically. In the time before heritage regulations were enacted, these recordings were also often limited to a basic inventory of items with descriptions and sometimes tentative provenience. Collections were then conserved through the boxing of materials, and stored in a dry, convenient location, often an attic, shed or basement (Latta 2004). These trends were evident in the state of the Rickley Collection when it was re-examined in 2013.

When the idea to repatriate the Rickley Collection arose, a thorough investigation was begun into its history and contents. An enormous amount of work was required to adequately organize the collection for repatriation. Beyond sparse information recorded on inventory cards, no documents were found that detailed the provenience, osteobiographical information, or long term plans for the remains that were collected from the Rickley site. Complicating this, over the years the collection became mixed with collections from other sites. The messy state of the collection contributed to the significant delay of its return, but with a comprehensive inventory of the collection finally completed in the summer of 2013, the committee could move forward with discussions regarding the next steps.

Small, but substantial collections like this undoubtedly remain hidden in attics or basements, forgotten, uninventoried and unanalyzed due to the poor standards for data collection when they were excavated. There is often little to no incentive for Canadian institutions to locate and process older collections in the present day.

Patience is a Virtue

Repatriation negotiations often take a significant amount of time to complete, sometimes continuing for years, as was the case with the Rickley Collection. In countries such as the United States and Australia, units established to deal exclusively with repatriation of ancestral remains —such as the Repatriation Office at the Smithsonian Museum in the U.S. or the Repatriation Program at the National Museum of Australia—and the formation of protocol and logistics strategies have streamlined the process (Goldstein 2014; Pickering 2010).

In Canada, however, there are no specific federal laws focused specifically on repatriation (Fisher 2012). Some museums have developed clear repatriation policies, but not all have a formal written protocol, which can hinder the process when claims are made. Miscommunication, legal limitations, and the absence of accounts detailing provenience and ownership can also contribute to lengthy repatriation timelines. In the case of the Rickley Collection, a combination of application wait times, personal obligations, and lack of administrative support stretched the process out over almost a decade.

In addition, for many communities, the practice of disinterring the dead is unprecedented, thus constructing ceremonies for their reburial requires a deep consideration of both traditional knowledge and contemporary subjectivities and practices (Lambert-Pennington 2007; Nahrgang 2002). The repatriation process is often slowed by the complex and varied customs of burial and treatment of the dead among those stakeholders involved.

Money Matters

The lack of funding and resources was another factor that significantly delayed the return of the Rickley Collection. For nearly 40 years, the collection was available for study, but aside from periodic student-led projects they remained unstudied. Interest in scientific research involving the ancestral remains in the collection was communicated in negotiations with the Heritage Centre, but when funding did not materialize it was decided that reburial would be undertaken instead.

Funding continues to be the major obstacle facing repatriation efforts (Fisher 2012). Museums, for example, seldom have funds to cover the costs of research on such collections. With the Rickley Collection, our funding only allowed us to conduct a basic inventory and some background site investigation.

Visits to collections by community members are also often required to complete the necessary preliminary ceremonies for the dead, which adds cost and time to the pursuit of repatriation. Community funding for these excursions is difficult to come by, which then limits the number of communities who can afford these efforts to return ancestral remains. In the case of the Rickley collection, a delegation from Walpole Island was able to come to the University to ceremonially visit the remains through a fund provided by the Aboriginal Education Centre.

(Left) student sketches of two projectile points found at Rickley in 1975. Image used with permission of the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Windsor.

In contexts where repatriation is guided by legislation, funding allowances have clearly been shown to hasten the process. For example, repatriation at the National Museum of Australia or at the Smithsonian Institution is a direct result of federal and state funding and has allowed for the establishment of the repatriation program units to facilitate the necessary research, act as a repository, and guide negotiations of the repatriation of human remains and objects of cultural significance (Pickering 2010; Rosoff 2003). Government-funded institutions like these proactively research, inventory and analyze collections of remains to determine their provenience and return them to identified descendent communities (Rowley and Hausler 2008).

Again, the limited budgets of First Nation communities in Canada do not often allow for the investigation of museum collections to retrieve ancestral remains and items of cultural significance. The needs of the living often come before those of the dead. As in the case of the Rickley Collection repatriation, discussions are often deferred until funding is secured and successful completion is guaranteed. The lack of available funds means that in many cases, First Nations communities in Canada simply cannot afford the necessary costs involved to return collections as may be required. Repatriation thus remains an elusive process for communities unfamiliar with the request process or lacking the resources needed for return.

Conclusions

In Canada, there is no federal policy facilitating the return of ancestral human remains from museums and cultural institutions to descendant communities (Gadacz 2012). Instead, Canadian First Nations and cultural institutions are guided by the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples (sponsored by the Assembly of First Nations and the Canadian Museums Association). The Task Force Report informs the ethical frameworks and guidelines established in museums and cultural institutions regarding Indigenous human remains and cultural items (Hill and Nicks 1992; Holm and Pokotylo 1997).

This lack of a coherent repatriation framework has both benefited and hindered the process in Canada. That is, while there is often no need for litigation, there is also no requirement of institutions to inventory collections or to provide funding to communities requesting repatriation. Questions of responsibility for the costs associated with the study, return and reburial in particular are raised as ancestral remains were generally removed without permission.

The repatriation of the Rickley Collection highlights how the state of collections and their documentation (or lack thereof), the lengthy process of negotiations and a lack of funding continue to directly impact the process of returning ancestral remains to descendent communities in Canada. These efforts showed that further ethnographic documentation of repatriation processes from a variety of institutions and communities will facilitate a more efficient and positive return of ancestral remains in the future.

Ultimately, efforts to repatriate ancestral remains remind us of the humanity of these individuals who once walked the earth, which is perhaps the most important lesson our team learned when returning these individuals to rest.

References Cited

Fisher, Darlene. 2012. Repatriation Issues in First Nations Heritage Collections. Journal of Integrated Studies 1(3).

Gadacz, Rene R. 2012. Repatriation of Artifacts. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Goldstein, Lynne. 2014. Repatriation: Overview. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith pp. 6327-6335. Springer, New York.

Hill, Tom, and Trudy Nicks 1992 Turning the Page: Forging New Partnerships between Museums and First Peoples: Task Force Report on Museums and First Peoples. Assembly of First Nations and the Canadian Museums Association. Ottawa.

Holm, Margaret, and David Pokotylo. 1997. “From Policy to Practice: A Case Study in Collaborative Exhibits with First Nations.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 21(1): 33-43.

Krmpotich, Cara. 2010. Remembering and Repatriation: The Production of Kinship, Memory and Respect. Journal of Material Culture 15(2): 157-179.

Krmpotich, Cara. 2014. The Force of Family: Repatriation, Kinship and Memory on Haida Gwaii. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Kroon, E. Leonard. 1975. University of Windsor Site Report: Rikley, 1975. Ms. on file, Ontario Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Recreation, London, Ontario.

Lambert-Pennington, Katherine. 2007. What Remains? Reconciling Repatriation, Aboriginal Culture, Representation and the Past. Oceania 77: 313-336.

Latta, Martha A. 2004. An Archaeological Generation: View from the New Millennium. Ontario Archaeology 77/78: 10-14.

Nahrgang, R. Kris. 2002. The State of Archaeology and First Nations. Ontario Archaeology 73: 85-93.

Ontario Provincial Government: Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport. 2011. Engaging Aboriginal Communities in Archaeology: A Draft Technical Bulletin for Consultant Archaeologists in Ontario.

Pickering, Michael. 2010. Despatches from the Front Line? Museum Experiences in Applied Repatriation. In The Long Way Home: The Meaning and Values of Repatriation, edited by Paul Turnbull and Michael Pickering, pp. 163-174. Berghan Books, New York.

Rosoff, Nancy B. 2003.Integrating Native Views into Museum Procedures: Hope and Practice at the National Museum of the American Indian. In Museums and Source Communities, edited by Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown, pp. 72-80. Routledge, London.

Rowley, Susan, and Kristin Hausler. 2008. The Journey Home: A Case Study in Proactive Repatriation. In Ultimut: Past Heritage—Future Partnerships, Discussions on Repatriation in the 21st Century, edited by Mille Gabriel and Jens Dahls, pp. 202-213. Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Recommended Reading

Gulliford, Andrew. 1996. Bones of Contention: The Repatriation of Native American Human Remains. The Public Historian 18(4): 119-143.

Kakaliouras, Ann M. 2012. An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice. Current Anthropology 53(5): 210-221.

Killion, Thomas W., and Paula Molloy. 2000. Repatriation’s Silver Lining. The SAA Bulletin: Working Together: Native Americans and Archaeologists 17(2): 111-117.

Morell, Virginia. 1995. Who Owns the Past? Science 268: 1424-1426.

Ramos, Harold. 2008. Aboriginal Protest. In Social Movements, edited by Susan Staggenborg, pp. 55-70. Oxford University Press, Toronto.

Rose, Jerome C., Thomas J. Green, and Victoria D. Green. 1996. NAGPRA is Forever: Osteology and the Repatriation of Skeletons. Annual Review of Anthropology 25: 81-103.

Sustainable Archaeology. n.d.

Chelsea is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University and an IPinCH Associate.