Production of Androgenetic Haploids and Diploids

(Source: G.E. Corley-Smith, C.J. Lim, and B.P. Brandhorst, Simon

Fraser University, B.C., Canada)

Immediately following is the protocol as printed in Eugene's

Zebrafish book in Aug 95. Refinements to protocol

Overview of procedure:

Androgenetic haploids can be produced by holding zebrafish eggs

in coho salmon ovarian fluid, irradiating them with 10,000 R of

x-rays, and then fertilizing them with normal sperm. To produce

diploid androgenotes, the same procedure is followed as for haploid

androgenotes, but is followed by inhibition of the first mitotic

division. The first mitotic division can be inhibited by various

methods. We use heat shock because it is easy to perform and control.

We will keep updates of the protocols on our www zebrafish server.

http://darwin.mbb.sfu.ca/imbb/brandhorst/zfish.html

Equipment Required to Produce Haploid Androgenotes:

1. Irradiation source. If using an x-ray source, it should

produce at least 150 KV. We purchased a Torrex 150D cabinet style

x-ray inspection system (Faxitron X-Ray Corp., Buffalo Grove,

IL., USA. phone: 708 465-9729). Based on research we have performed

using salmon eggs, we believe gamma rays should also work well

for zebrafish eggs.

2. In vitro fertilization supplies. As outlined

in this book under Delayed In Vitro Fertilization Using

Coho Salmon Ovarian Fluid.

Additional Equipment Required to Produce Diploid Androgenotes:

1. Hot water bath. Set to maintain fish water in a beaker

at 28.50.5C. Fish water is a term we apply to the water we use

for raising fish. If desired, embryo water (refer to Recipe Section

of this book) can be used in this protocol, wherever fish

water is indicated. Since timing of the first mitotic division

is temperature dependent, accurate temperature control of this

hot water bath is particularly important for producing diploid

androgenotes.

2. Second hot water bath. Set to maintain fish water in

a beaker at 41.4±0.05C. A calibrated thermometer is required

for this accuracy (e.g. Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 15041A). Inside

both hot water baths we have beakers containing fish water. To

promote heat transfer, the water in the beakers is constantly

stirred using either a stir paddle or a magnetic stir bar. Temperatures

should be measured in the beakers, since water temperatures in

the beakers are usually slightly lower than in the surrounding

water baths due to thermal loss from evaporation.

3. Heat Shocking Tubes. To transfer eggs between hot water

baths and allow for abrupt thermal changes to be applied to the

eggs, we use uncapped 50 ml polypropylene conical tubes from which

the bottoms have been sliced off and a fine mesh melted on. We

use 153µm pore size Nitex mesh on these heat shocking tubes.

Collection of Eggs:

We collect eggs into approximately 100µl coho ovarian fluid

located in the centre of a 50mm diameter petri dish.

Irradiation of Eggs:

We irradiate eggs at 23 cm from the focal point of the x-ray beam

of the Torrex 150D (shelf 8). Settings used are 145 KV and 5 mA.

X-ray dosimetry indicates that at this distance and electrical

setting, the x-ray output is 12.2 R/sec. Thus, we irradiate for

820 sec to achieve a total dose of 10,000R. Eggs are irradiated

in coho ovarian fluid at room temperature. We attempt to have

a monolayer of eggs with as thin a layer of ovarian fluid over

eggs as possible. The Torrex 150D has a built in 1.2mm beryllium

window. We use no extra filters, as they extend the time required

to deliver 10,000R. If an x-ray machine with sufficient output

is used, a 0.5mm aluminum or copper filter will help to selectively

remove soft x-rays. Soft x-rays (low KeV) are suspected of causing

more cytological damage than hard x-rays which are more selective

in targeting DNA.

Fertilization of Eggs and Production of Haploid Androgenotes:

Proceed as described in Delayed In Vitro Fertilization

using Coho Salmon Ovarian Fluid described in this book.

Embryos that subsequently develop and exhibit the haploid syndrome

are putative haploid androgenotes. No embryos having diploid appearance

should be observed.

Heat shocking to produce diploid androgenotes:

1. Start timer as soon as 0.5 ml of 28.5±0.5C fish water

is added to milt and eggs. This is time = 0.0 minutes.

2. Place petri dish in a 28.5 °C incubator or on a shallow

ledge in a beaker containing 28.5 °C water. After 1 minute,

very gently add 28.5C water to 3/4 fill petri dish.

3. At 5 min, transfer eggs to a heat shocking tube (50ml tube

with net bottom) and suspend tube in beaker containing 28.5C fish

water that is in water bath. Tubes should be suspended, not rested

on bottom of beakers and should be left uncapped.

4. At 13 min, transfer heat shocking tube containing eggs to beaker

containing 41.4C fish water.

5. At 15 min, very gently transfer heat shocking tube containing

eggs back to 28.5C beaker and leave there undisturbed for 1.5

h.

6. After 1.5 h, transfer eggs very gently into petri dishes 3/4

full of water and place in a 28.5C incubator.

7. At 24 h, view developing embryos under dissecting microscope.

At 24 hours, if many haploid and no diploid embryos are observed

in the irradiated and non-heat shocked group, any embryos in the

irradiated and heat shocked group that have a diploid appearance

should be diploid androgenotes.

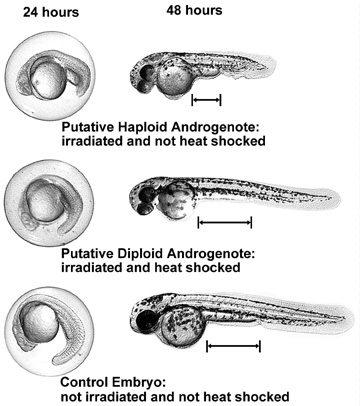

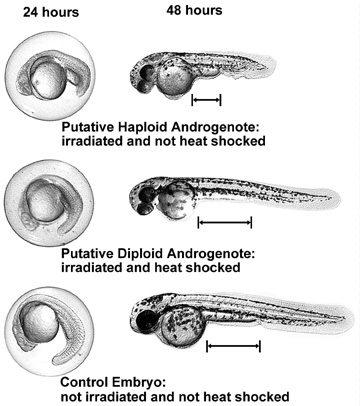

Assessing Putative Haploid and Diploid Androgenotes:

When attempting to produce diploid androgenotes, it is advantageous

to have at least three groups of eggs: 1) normal diploid control

group; 2) irradiated and not heat shocked (putative haploid androgenotes);

3) irradiated and heat shocked (putative diploid androgenotes).

After collecting eggs, put a small group of eggs aside (control

group) and irradiate the rest. Fertilize all eggs at same time.

Part of the irradiated group can go into 28.5C incubator (potential

haploid androgenotes), and the rest are heat shocked (potential

diploid androgenotes). The control group is to ensure that delayed

in vitro fertilization is working and to allow for the

visual comparison of putative haploid and diploid androgenetic

embryos with normal diploid embryos, as well as for genetic analysis.

Two phenotypes that must be recognizable by the researcher are

the diploid phenotype and the haploid phenotype. Haploid embryos

exhibit what is called the haploid syndrome: shortened body, small

melanocytes. The haploid syndrome can be seen at 24 hours as a

shortened body phenotype (Figure 1). At 48 hours, the shortened

body is easily noticeable and the difference in melanocyte size

starts to become noticeable (Figure 1) and is pronounced by 96

hours (not shown). The development of androgenetic diploid embryos

is initially retarded in relation to diploid control embryos (Figure

1). However, by the end of the first month, the androgenetic diploids

achieve approximately the same size as the diploid control fish.

Figure 1: Comparison of haploid and diploid androgenotes and normal

diploid embryos at 24 and 48 hours. Three embryos are shown, each

at two different stages of development. Note: the distance between

the posterior yolk sac margin and the anal pore is greater for

the diploid phenotype than for the haploid phenotype. Click on

image to get higher resolution image (791 KB).

Figure 1: Comparison of haploid and diploid androgenotes and normal

diploid embryos at 24 and 48 hours. Three embryos are shown, each

at two different stages of development. Note: the distance between

the posterior yolk sac margin and the anal pore is greater for

the diploid phenotype than for the haploid phenotype. Click on

image to get higher resolution image (791 KB).

We originally determined the irradiation dosage based on the Hertwig

effect (Hertwig, 1911). To ensure that the irradiation dose is

adequate to destroy the maternal genome in each experiment, we

always include an irradiated and nonheat shocked group. No diploid

phenotypes should ever be observed in this group. If no diploid

phenotypes are observed in the irradiated and non-heat shocked

group, then it is likely that diploid phenotypes in the irradiated

and heat shocked group are androgenetic diploids.

Confirmation of exclusive paternal inheritance requires investigating

the inheritance of parentally polymorphic DNA markers to putative

androgenetic progeny. The lack of homozygous maternally specific

markers in the progeny is strong evidence supporting sole paternal

inheritance, although it does not rule out the possibility of

some maternal leakage.

References:

Hertwig, O. 1911. Die Radiumkrankheit tierischer Keimzellen. Arch.

Mikr. Anat. 77, 1-97.

Die Radiumkrankheit tierischer Keimzellen

means

Die: The

Radiumkrankheit: Radium Disease

tierischer: of animal

Keimzellen Germ Cells

Acknowledgments:

We are indebted to Charline Walker for the *AB line of fish, and

for her extremely helpful advice on in vitro fertilization

and on heat shocking zebrafish eggs.

Updated on August 1995: Tentative results suggest that improved

survival of diploid androgenotes may be achieved by ramping the

heat shock temperature from slightly below the final temperature,

up to the final heat shocking temperature during the first minute

of heat shocking.

Return to List of Protocols

Return to zebrafish home page

Figure 1: Comparison of haploid and diploid androgenotes and normal

diploid embryos at 24 and 48 hours. Three embryos are shown, each

at two different stages of development. Note: the distance between

the posterior yolk sac margin and the anal pore is greater for

the diploid phenotype than for the haploid phenotype. Click on

image to get higher resolution image (791 KB).

Figure 1: Comparison of haploid and diploid androgenotes and normal

diploid embryos at 24 and 48 hours. Three embryos are shown, each

at two different stages of development. Note: the distance between

the posterior yolk sac margin and the anal pore is greater for

the diploid phenotype than for the haploid phenotype. Click on

image to get higher resolution image (791 KB).