Thanks to “fast fashion”—the availability of trendy, low-quality clothing designed to be worn and discarded—North Americans send a staggering 10 million tonnes of textiles to landfill each year.

Naomi Krogman is the Dean of SFU’s Faculty of Environment and professor of resource and environmental management. One of her research focuses is sustainable consumption. With the intense use of resources and the clothing waste created by the fashion industry, she wanted to understand why Canadians produce so much post-consumer clothing waste and what alternatives were available.

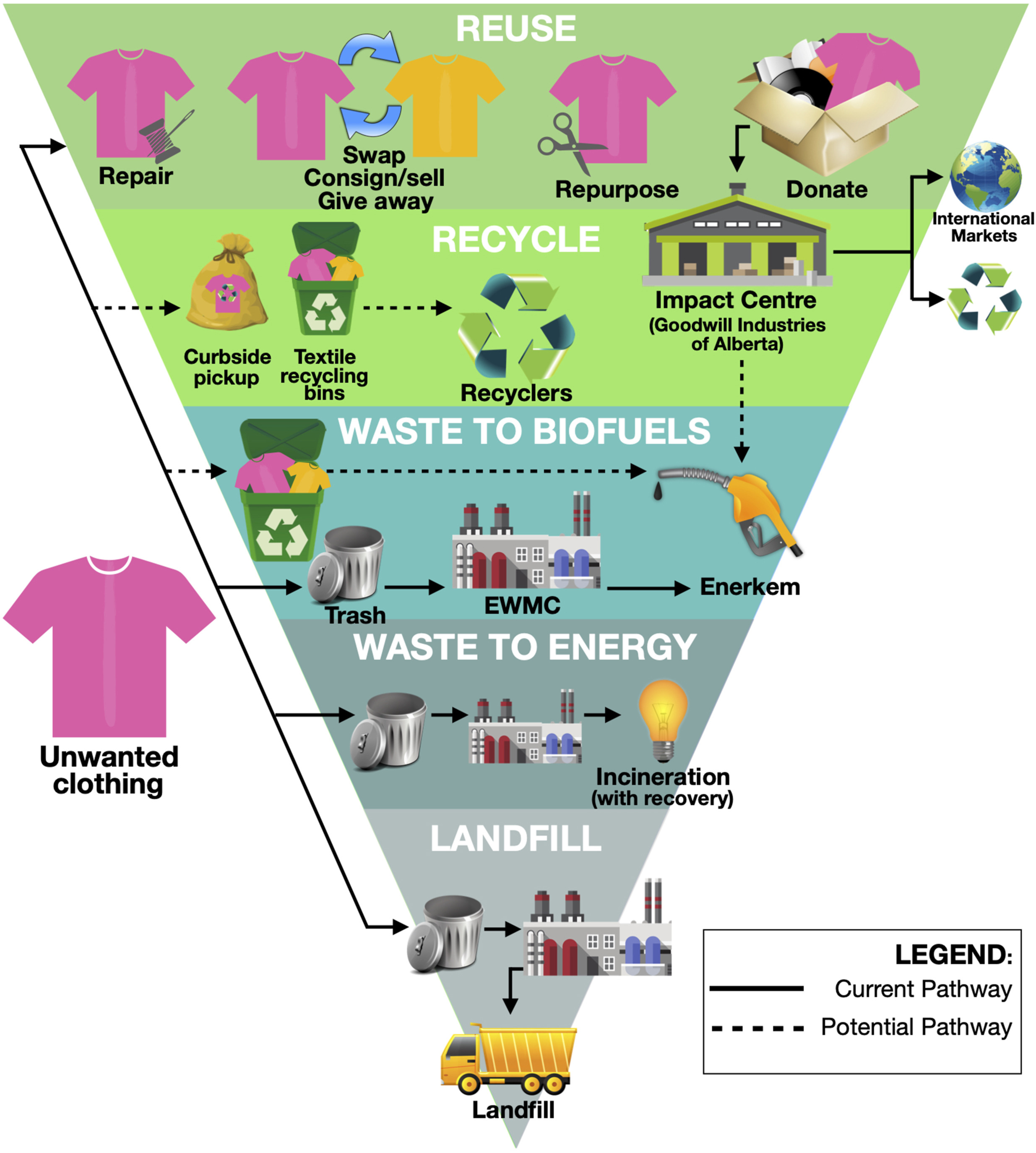

Krogman collaborated with researchers Lauren Degenstein and Rachel McQueen from the University of Alberta to study how the City of Edmonton deals with unwanted clothing. Current options include donating, repurposing and landfilling. As well, the City offers a unique waste-to-biofuels initiative that is currently underutilized, while the study survey found Edmontonians are interested in sustainable options.

The authors’ paper ‘What goes where’? Characterizing Edmonton’s municipal clothing waste stream and consumer clothing disposal suggests ways for municipalities to redirect textiles from landfill and give them a second life. (SFU login required for free journal access).

We met with Krogman, Degenstein and McQueen to discuss their study.

Can you summarize your recommendations for ways cities can reduce and redirect unwanted clothing from landfill?

In this research, we explored current pathways for unwanted clothing and disposal habits of Edmontonians. Recommendations from our research require collaboration between municipalities, citizens, and businesses to better integrate waste management streams and take advantage of existing opportunities while circular solutions are scaled. Strategies such as public education campaigns to communicate the impacts of trash disposal of clothing, teaching repair skills, informing citizens on the conditions of clothing suitable for different disposal methods, and providing people with convenient means of disposal (e.g., clothing bins and curbside textile pickup for unusable textiles) would help divert textile waste from landfill.

Consumers in Edmonton appeared open to options for sustainable clothing disposal. What are some of the barriers that prevent them from recycling or upcycling waste clothing?

Unlike paper and plastic recycling where there is curbside pickup, options for sending clothing for recycling aren’t easy due to the varying qualities and fibre types of clothing and the potential for textiles to become moldy when wet. There is also a lack of convenient disposal options, uncertainty around what items are acceptable for donation and the options for unusable clothing. People may not have the skills, time or inclination to turn clothing they don’t wear into something else. The cost of purchasing new clothing can be perceived as a less expensive option than paying for garment repair or alterations.

During the pandemic, has the interest in fast fashion waned? If not, do you think it ever will?

Fast fashion consumption seems to have waned during the pandemic. In an unpublished study by McQueen of 514 Canadian and U.S. consumers, about 60 per cent stated they buy less fast fashion garments during COVID-19 (data collected March to May 2021). However, only about 40 per cent of them indicated they were more concerned about sustainability of garments since the pandemic began, and would be much more likely to buy locally. A U.K./German study found Generation Z (ages 18-23) and Millennials (ages 24-39) were also more likely to shop for secondhand clothing and repair clothing as part of a behavioral shift due to the pandemic, although we don’t know if these behaviors will persist.

Do developing countries really want bales of unwanted clothing? Is sending clothes overseas a viable option?

Thrift stores receiving vast quantities of clothing cannot sell poor quality clothing. Data collected by one Canadian thrift organization indicated that at their largest store in Vancouver about 20,000 items of clothing are donated every month, with about 55 per cent being unsaleable, recycled or destined for landfill. There are vibrant secondhand economies in low-income countries and yes, our secondhand clothing can be desired—but we should be sending clothing that they want so we are not just offshoring our textile waste. Finding solutions within Canada to recycle our unwanted textiles is the best solution.

What is next for this line of research?

Finding solutions for unwanted textiles that aren’t suitable for reuse in their current form is essential. At the consumer level, this would involve promoting sustainable behavior change such as buying less, purchasing higher quality clothing and textiles, and repairing clothing when needed. From a broader perspective, scalable textile recycling solutions are needed to handle our vast amounts of unwearable clothing. We also need to explore the types of policy levers that will discourage overproduction and textile landfill disposal while incentivizing reuse, repair and recycling.

SFU's Scholarly Impact of the Week series does not reflect the opinions or viewpoints of the university, but those of the scholars. The timing of articles in the series is chosen weeks or months in advance, based on a published set of criteria. Any correspondence with university or world events at the time of publication is purely coincidental.

For more information, please see SFU's Code of Faculty Ethics and Responsibilities and the statement on academic freedom.