Section 2.6 Heiltsuk - HAULAɫAS - HÁUSA DU GLW̓A

Written by: Veselin Jungic and Mark MacLean

Illustrated by: Simon Roy

Heiltsuk translation by: Constance Tallio and Evelyn Windsor

Haulaɫa'uis wísm háusláya, Gi hiálaq̓am nánúɫtuba la.

Small Number is a little boy, and he is always getting into mischief.

'Císlasuis ǧaqǧṃ́pási,'Ksay̓asi wán̓iqas hialama h̓áml̓ínisi.

He is in the care of his grandparents, for, they put up with the way he plays.

'Kiágilaxv ǧaǧmpasi ɫúq̓va λiálac̓iƛ, Gi h̓auá yápa háusḷá' qn láisi, h̓ámɫuls du w̓áukvas x̌ix̌apxv.

Grandpa has to carve a feast dish, “go out and play with the other children.”

Háixƛalapsis hay̓ṇ́x̌s pxlas k̓vqḷá, gi h̓auá k̓ík̓x̌vnc̓s lá h̓ámɫa la w̓a'ámpax̌i.

It's a nice spring sunny day, and they ran down to play in the water.

'Hákq̓aṃ̓ás duqvlasusi wáli q̓áyax̌'aidailas h̓áluɫts h̓áml̓íní, Gi h̓auá q̓ay̓ax̌'ait 'Qaikasas klxsm qn h̓ágvaƛiay̓alanás t̓ísm gila c̓x̌'áitsi la w̓a'ampax̌i.

Everything they see sparks a new game, and Small Number's friend Big Circle suggests they see who can make a stone skip the farthest on the surface of the water.

Hál̓akaiq̓a' áuɫ'aƛḷa wi'ísmáx̌i n̓ax̌vi msḷá qn x̌vísgílís t̓ísm hiáǧlmsi yíáqɫgiláy̓asi paɫtus glɫtúxst̓uxvs tism.

The boys learned if they want their stones to go far, they had to use a flat oval shape stone.

Yiálaglis Háuláɫas Háusḷá x̌víx̌vsgílá líta t̓ísmáts h̓áikuáy̓u.

Small Number walked far looking for the rock that will win.

Tuá laglisi la k̓ítṃ́isax̌i gi h̓auá q̓áq̓nx̌ṇála m̓núxvs m̓ás. Kíx̌c̓u xvák̓vná guɫdia t̓áy̓álá la k̓ít̓ṃáx̌i.

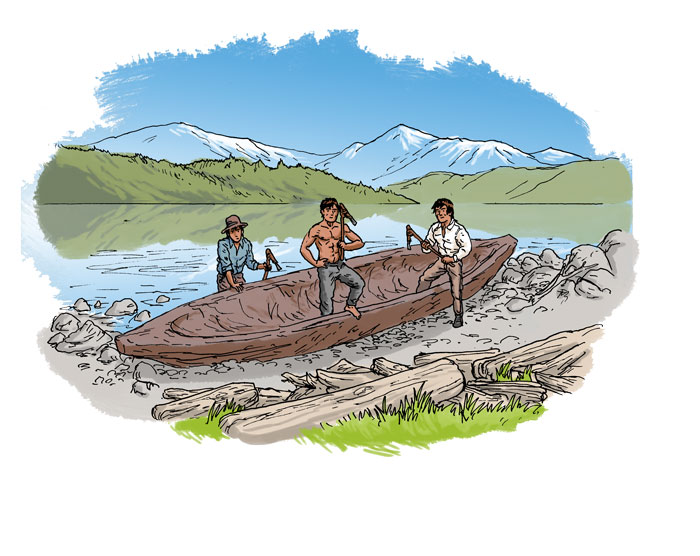

He was walking in the grassy area and he kicked into something, and fell head first into an old canoe hidden in the grass.

Waxv'ṃi ƛ̓uxválá háixt̓iási gi w̓alas h̓áik̓qḷas q̓ákanx̌vasi. Yáux̌vḷi w̓áukvasi gi h̓aua k̓ík̓vḷá lákáqi.

Even if he hit his head he was very happy over his find. He called out to his friends, they went running to him.

λaxλuis wi'íṃáx̌i la w̓uistayas xvákvṇáyax̌i. 'Pakaxdax̌vu wuwakiax̌six̌s xvákvṇáyax̌v.

The boys were standing around the canoe. They were touching the sides of the canoe.

ǧaialaxst̓uxv'ila q̓áikast̓uxv.

It looks old and looks big to them.

Gi h̓auá haúmá Háuláɫas Háusḷá, Gṇ́acáukvix̌ndilic 'ƛíƛuw̓lstuá lay̓acx̌v x̌sílásu?

Small Number asks, “How many generations ago was it built?”

Gṇ́caukvi dítgváṇm xvutiy̓aus qn haiɫx̌v láx̌v 'quik n̓ix kl̓xsm.

“How many people do you think will fit in there?”, asked Big Circle.

'ƛ̓lístaq̓am wi'ísmáx̌v h̓áml̓ínáy̓asi.

The boys forgot the game they had been playing.

Gi h̓auá pk̓váláq̓ams glw̓áyáx̌i q̓a'áuƛ̓ix̌sda yiaqɫats glw̓aka'auax̌i.

They were talking about the canoe wondering who could have used it.

La bípk̓váláy̓asi 'Qvúml̓áláx'it tk̓iás 'Qáikas Kl̓xsm.

As they were talking Big Circle's tummy began to growl.

Puw̓ísṃṇúgva 'waixsints hmsa, niki w̓áukvasi, Gi hauá k̓íkx̌v'it lái n̓akv.

I'm hungry “Let's go eat”, he says to his friends, and they all ran home.

'Kíx̌vla Haulaɫas háusḷá láin̓akv, La la'asas ǧaǧṃpasi k̓iálagiɫ wusǧmiy̓as q̓áikaska'áuás ɫúq̓va.

Small number ran home, at the place where Grandpa was carving the surface of a huge (wooden) dish.

Gi h̓auá h̓átḷá, Gi h̓auá t̓ix̌sísta dúx̌v'it.

And he shouted, and he looked up

Dúqvḷái h̓áxváyá la w̓úgvíwáyas háuláɫas háusḷá.

He saw the bruise on Small Number's forehead.

'Wíx'ítxdas nix ǧáǧmá háum.

“What happened?” asked Grandpa.

'ƛlísta háulaɫas háuslá-ya lay̓asi t̓s'ála háixt̓iási, gi niɫas qakay̓si gḷ́w̓a.

Small Number had forgotten that he bumped his head and started to tell Grandpa about finding the canoe.

'Qákánúgva glw̓a gvauɫ la wil̓iax̌i laganmits w̓úp̓nxstáis'ila w̓ása̓lásasi.

I found an old canoe down on the beach. It must be at least a hundred years old.

Mḷ́xvlá ǧáǧámpa q̓a'áuƛṇugva gḷ́w̓áyáx̌i Mnúkvis yixálágvuts gḷ́w̓as qnts gvúkviásax̌.

Grandpa smiled, “it was one of the fastest canoes of our village”.

'Hámƛ̓asugvauɫis qs h̓aumpa du má'álukvas w̓aq̓vásí.

“It was built by my father and two of his brothers.”

Níɫtu ǧáǧmpa gi níɫas 'hágám sásmás qs ǧáǧmá q̓a'áuƛ̓nx̌vs yis w̓alas h̓áikímás k̓iá.

Grandpa proudly continued, “all the sons of my grandfather were known as the great carvers”.

'Ga'áuɫ'msu qi yúdúkvas c̓uw̓áx̌si la w̓uw̓áx̌siás λiác̓iax̌i?

“You know those three (old) totem poles in front of the bighouse?”

'Hágámi k̓iásus qs m̓núkvas xvɫmp.

“Each of them was built by one of my uncles.”

Mnúkvis ǧánúɫ h̓ábas laxstasaiɫay̓asi qn k̓aɫ'it x̌sílíx̌sdnugva du 'cuw̓áx̌sigila ǧviála qs h̓áiámbiɫgvaiɫdia.

One evening before going to sleep, Small Number thought, “I'd like to build a canoe and totem poles just like my ancestors”.

Háumáƛṇugva ǧáǧmá ɫansƛats gncaukv w̓íw̓aq̓váyaci h̓aumpasi, ma'alukv, yúdúkv, múkv, sk̓aukv, dun̓ax̌vi q̓áinám.

“I will ask my grandfather tomorrow how many brothers his father had, two, three, four, five or more.”

'Mási xvútagiɫts háuláɫ'uas háusḷá qits ma'áluxv, yúdúxv, múxv, sk̓a̓úxv ǧáǧasl̓ayats ǧáǧmpasi.

Question: Why did Small Number think his great grandpa had two, three, four, five great grandparents?